Chinese has been classified as one of Australia’s four most important strategic Asian languages since the 1990s and has been vigorously promoted nationally for about three decades. However, currently students are insufficiently considered in planning around language teaching.

Since the 1950s, scholars have paid more attention to the motivations of second language (L2) learners. Exploration of motivational studies on learning Chinese as a Foreign Language (CFL) or learning Chinese as a Heritage language (CHL) has been conducted world-wide in the past two decades. But very few motivational studies have looked at CFL/CHL students’ motivation in the Australia tertiary context since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. The pandemic had a significant influence on why students chose to learn a language and how classes are delivered.

We recently investigated the reasons behind 58 university students’ decisions to study Chinese and how their motivations changed throughout the pandemic. From July to November 2022, these 58 students (at the University of Melbourne and Monash University—two of Australia’s largest and most prestigious universities) filled out a survey and 18 members of that group also participated in in-depth interviews. We aimed to draw an updated profile of Chinese language learners at tertiary level and look at the main factors behind students’ decisions to continue to study Chinese based on the most influential L2 motivational framework by psycholinguist Zoltán Dörnye.

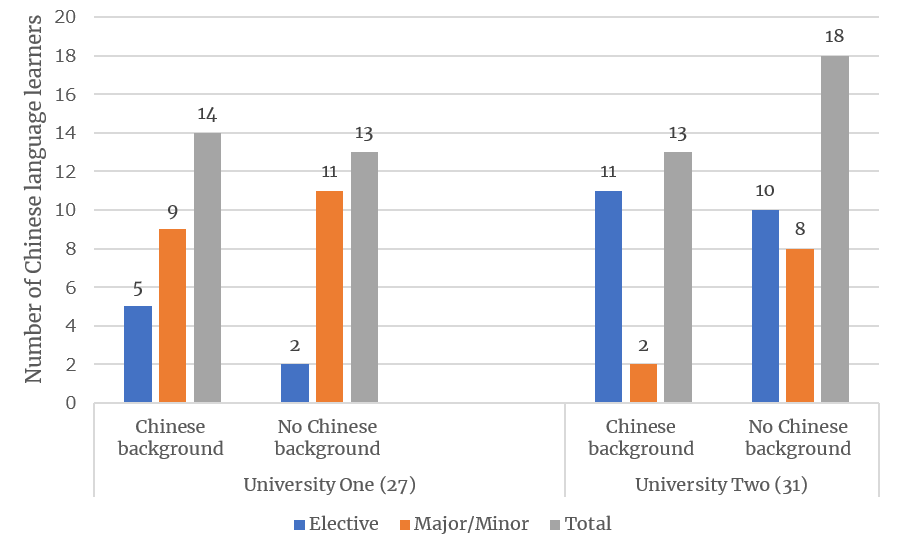

Figure 1: Participating Chinese language learners at the two universities

The Chinese language programs at both universities range from beginners to advanced levels. As shown in Figure 1, overall, slightly fewer students choose Chinese as a major/minor (28) than those who choose Chinese as an elective (30). The trend is more prominent at University One. Of a total of 58 students who responded to the survey, 27 had a Chinese background, commonly known as heritage learners (i.e., CHL), and 31 did not have a Chinese background (i.e., CFL).

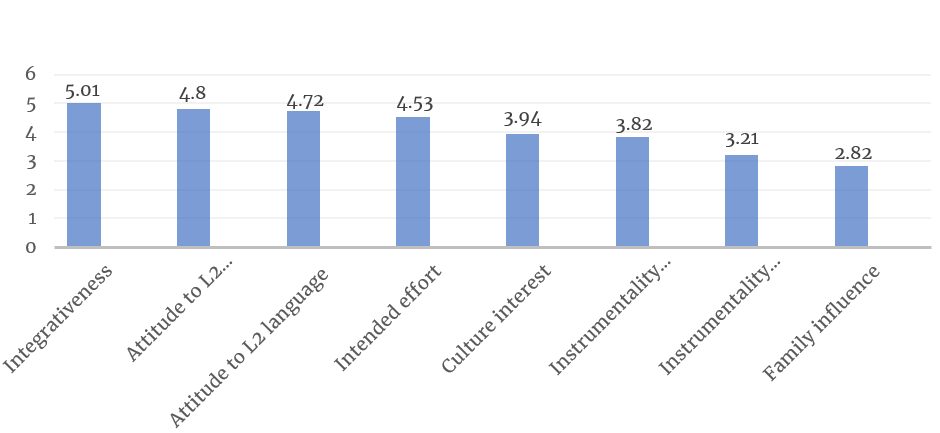

Figure 2. Mean of each motivational factor of students as reflected in the survey data

According to the results from the six-point scale survey (see Figure 2), the most significant factor that affected motivation was ‘integrativeness’, which is generally understood as a desire to interact with the people and culture of the target language. The second and third most significant motivational factors were ‘attitude to community’ which investigates the learners’ attitudes toward the community of the target language and ‘attitude to language learning’, which refers to situation-specific motives related to students’ immediate learning environment and experience.

Instrumentality (promotion)—which measures students’ personal goals, such as to find a better job or earn more money by attaining high proficiency in Chinese)—was not as significant a motivating factor as anticipated (Mean=3.82 out of 6). Similarly, instrumentality (prevention))—which assess how influential that responsibilities and obligations are, such as learning Chinese to pass an exam)—is clearly not as important as other motivating factors.

‘Family influence’ was rated as the least most significant factor in motivation. This suggest that students’ did not believe that family factors, such as direct or indirect support, understanding, and encouragement has a direct impact on their drive to learn a second language.

Case studies

As stated above, 18 of the 58 students who filled in the survey also participated in in-depth interviews. Students were asked about:

- their past experience e.g., the most pleasant/unpleasant memory or other factors that influenced their Chinese learning,

- their goals and future plan for learning Chinese; and

- possible changes to their motivation due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Below, we look at four case studies: two non-Chinese background students (i.e., those who were learning Chinese as a foreign language) at beginner level, and two heritage language learners at advanced level.

Motivations of those learning Chinese as a Foreign Language (CFL)

CFL learners, in contrast to heritage language learners, usually begin their language study with a strong internal motivation. *Mini and *Andy (all names throughout are pseudonyms) are two CFL beginners who both took Chinese as a subject at secondary school.

Mini is from Arabic speaking background majoring in Chinese. Although she stated that she chose Chinese as her university major because ‘it was the only one’ at her university that she was interested in, her ongoing self-study using online resources demonstrates her tremendous on-going motivation. Mini’s motivation for learning Chinese is closely related to visualising herself in workplaces using Chinese to engage with others: ‘I want to achieve a level of fluency where I can comfortably interact with Chinese speaking people. I’ll definitely be able to use it, […] career-wise’. Additionally, Mini had a favorable perspective towards Chinese language and the Chinese community because of a cultural exchange trip to China in secondary school. She emphasised how much her first Chinese teacher’s enthusiasm at that time had inspired and motivated her. Teachers at her university also provided her with an encouraging learning environment so that her fear of online learning greatly decreased. The experiences of Mini reflected the findings of the surveys, which found that learners’ attitude towards Chinese language and Chinese community were a motivational factor, largely influenced by their learning experiences.

*Andy also stated that he was hoping to use Chinese in his future employment. We therefore concluded that instrumental factors such as employment were a strong motivation factors for both CFL students. Unlike Mini, Andy stated that his motivation was significantly impacted by his family, many members of which spoke a European language as well as English, and his father spoke five languages. He thought of learning Chinese as ‘a minor renovation’, meaning he continued the family’s language skills but with an Asian language. Also significant is that Andy chose Chinese because of his university’s ‘breadth subject’ requirement (a breadth subject is a subject from a different area of study to the degree, which gives students the opportunity to gain knowledge outside of their main fields of study). Although Andy did not express a positive experience of learning Chinese at primary school where ‘he learned nothing’ or at secondary school where ‘he was sick of it’, he stated an intention to continue with Chinese for all his breadth subjects. Additionally, Andy did not seem to be confident in his learning ability and he had started his university study of Chinese at a lower level than his previous study levels suggest. It appears that Andy’s Chinese learning motivation is complex, being negatively affected by his prior learning experience, but also affected by both family influence and instrumental factors.

Motivations of those learning Chinese as a Heritage Language (CHL)

*Green and *Eden (pseudonyms) were two advanced background speakers who participated in in-depth interviews. As heritage language learners, their continuous exposure to the Chinese language had a significant impact on their motivation. Green primarily speaks English and studied Chinese in primary school. Her parents speak English at home, but her mother can speak Mandarin fluently. Her motivation for Chinese language learning mostly lies in ‘self-improvement’ and ‘family influence’: ‘My parents, actually my mum…it’s very inspiring for me to see her have complicated conversation in Mandarin with her Chinese colleagues.’ It is also worth emphasising that Green said she was very motivated by her enjoyment of her university Chinese course which was more culture oriented and better structured than her primary school.

*Eden expressed very similar motivations to Green: family influence and personal growth. Eden’s father speaks Cantonese and his mother speaks Vietnamese. Eden started his Chinese learning journey from primary school because of his parents’ expectation. Eden also stated that he wanted to improve his Chinese for future employment, because ‘it is one of the most common languages in the world,’ however he said that ‘it is not at the forefront of the priority list’ when we talked about his learning goals. This indicates a shift in Eden’s motivation for learning Chinese, which might be impacted by the change to online learning during COVID-19 lockdowns. Eden stated that the lack of interaction with peers and teachers made him dislike remote learning.

COVID-related changes to students’ motivation

Eden had experienced three different learning modes, on-campus, online, and mixed mode, at university since the pandemic began. He spoke of his diminishing motivation due to remote learning because ‘I love to do things in person’ and he felt ‘isolated’ and ‘secluded’ from peers and teachers. He stated that ‘I would probably be in conversation classes…I am looking more for being in that space with other people who want to speak and practice the language more’ as his future learning plan.

Mini also conveyed a negative experience of online learning by describing it as ‘demotivating’ and ‘pointless’, however she also stated that she is less intimidated by speaking Chinese in front of a screen than in person. This is echoed by Andy who stated that online learning could help him be less ‘anxious’ while learning a second language.

Compared with other interviewees, Green held more positive views on the mixed mode of learning common in university courses in 2022. Green stated ‘I think online makes people feel more confident to speak in second language, because you are behind the camera.’ She also said that ‘sometimes in class, [..]it’s not so easy to search class-relevant stuff online. If you are searching something when teacher’s talking, it may look like you are not paying attention. But over Zoom, the teacher can’t really tell’.

Conclusion

The reasons that affect learners’ motivation to learn Chinese at Australian universities are varied. Integrativeness—learners’ strong desire to be integrated with the Chinese community and Chinese culture—was the top motivating factor among those who were surveyed.

In the in-depth interviews, both CFL beginners, Mini and Andy, stated that they were motivated by the future use of Chinese during employment. The two interviewees with heritage backgrounds tended to place a higher priority on personal development than external factors and were highly influenced by their families. Their on-going exposure to Chinese and Chinese culture has a big impact on how motivated they were.

More research needs to be done in relation to the motivations and preferences of students who have experienced online learning and dual-mode learning (online and in-person). Some students report that their motivation decreased because of having less interaction with classmates and teachers, but some students found advantages in online learning, including greater learning flexibility and convenience as well as feeling less anxious. With the development of online technology and innovative pedagogies, whether and to what extent students’ L2 motivation will change and how their motivation will be sustained in either online learning or mix-mode learning requires further exploration and wider sampling.

Authors: Tracy Huahua Hong & Dr. Hui Huang

*All names of those within the article are pseudonyms

Image: Students in a classroom. Photo by javier trueba on Unsplash