On Monday 15 December 2014, Man Haron Monis, an Australian citizen claiming to be a Muslim and displaying what appeared to be an ISIL flag, held 18 people hostage in the Lindt Café in central Sydney. The incident resulted in the death of two hostages and Monis was shot dead by the police when they raided the café.

On Friday 19 December 2014, having the approval to do so, the author and her assistants, recorded 14 sermons delivered across 11 major mosques in Sydney, strategically selected to be representative of the diverse backgrounds of Muslim-Australians. The recordings were transcribed and the content was analysed. Focus was placed on the extent to which audience members were encouraged by the imams to engage and interact with members of the wider Australian society in the aftermath of the incident.

Of the 14 recorded sermons, eight covered the topic of the Lindt Café Siege. Delivered less than a week before Christmas, three of the 14 sermons were dedicated entirely to the topic of Christmas.

The sermons revealed the imams did not see any Islamic justification for the attack at the Lindt Café and encouraged their audiences to offer their condolences to the victims. Their audiences were also encouraged to engage with members of the wider Australian society and demonstrate through their actions that Islam is a religion of peace. In this context, imams were found to propagate and promote interaction and engagement with the religious ‘other’.

However, in the sermons relating to Christmas, imams depicted it to be an event that contradicts Islamic beliefs and practices. In this context, Muslims were discouraged from engaging and participating in Christmas-related events and ceremonies.

The sermons are significant in the context that over the past three decades, Muslim-Australians have faced high rates of racism and discrimination. The reasons for this can be traced to a diverse range of factors, including media misrepresentation and a political climate antagonistic to Islam and Muslims. However, Muslim-Australians can still exercise some influence over mainstream perceptions of them. Researchers have found that increased knowledge of Islam and interaction between Muslims and non-Muslims can play an important role in reducing the prejudice and hostility felt toward Islam and Muslims.

Sydney’s imams and Friday’s congregational prayers

Every Friday, approximately 35,000 Muslims (mostly men) living in the Australian state of New South Wales attend what is referred to as Jum’ah prayers. Mature, healthy and capable Muslim men are encouraged to perform their prayers at the mosque and with the congregation. This participation is a religious obligation—negligence carries spiritual consequences for believers. In Sydney, imams are mostly appointed by the mosque committee or otherwise are representatives of the Imams Council or volunteers from the community.

While most aspects of the imam’s role are largely scripted, repetitive and predictable, the responsibility for delivering the mosque sermon offers imams the opportunity to speak on a topic of their own choosing. In Sydney, the imams mostly decide the topic of the sermon.

Though somewhat dependent on demographic variables and the sermon’s quality, most audience members who attend Friday’s congregational prayers listen attentively and accept the message delivered by the imam. Though an inclusive aspect of a religious ritual, the sermon delivered by the imam has the capacity to influence the attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of their audience. Thus, the topic of whether imams encourage or deter Muslims from interacting and engaging with members of the wider Australian society warrants close examination.

Recording the mosque sermons

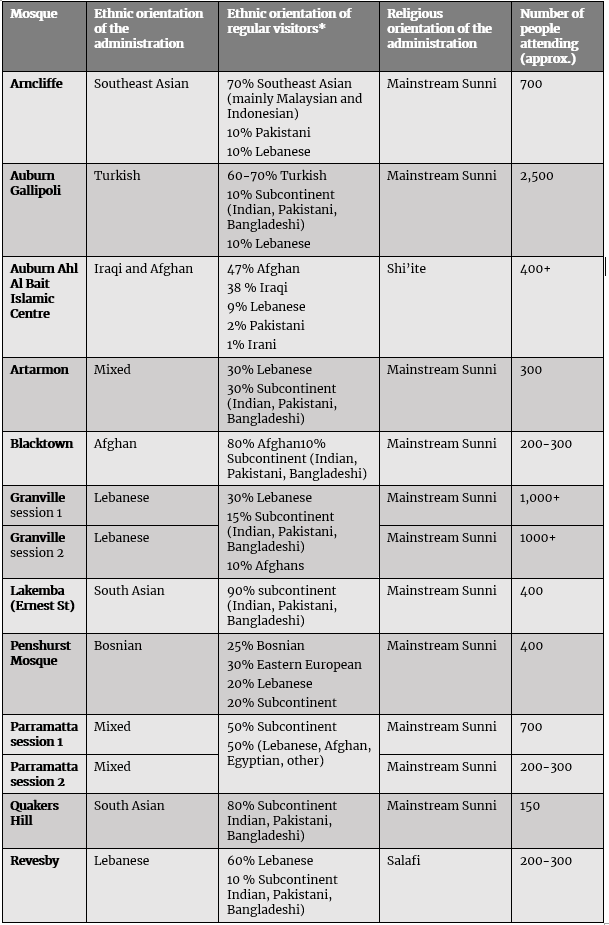

The mosques where the recordings took place were selected to be representative of the diverse ethnic, religious and occupational backgrounds of Muslim-Australians, as identified by the characteristics of the mosque administration and regular attendees (see Table 1). Moreover, it was important for recordings to take place inside the biggest mosques in Sydney as identified by the number of people who attend for their daily and Friday’s congregational prayers. Based on the statistics available at the time of research, the dominant ethnic backgrounds of NSW’s Australian population were Australian-born (37.6 percent), followed by those born in Lebanon (7.1 percent), Pakistan (5.6 percent), Afghanistan (5.5 percent), India (2.1 percent) and other countries (23.2 percent).

For example, Lakemba Mosque (Ernest Street) was selected to be representative of Muslim-Australians of a South Asian background as the imam who delivers the sermon and most of the congregation who attend are South Asian. Auburn’s Gallipoli Mosque was selected for inclusion as it is not only one of the largest, but also because approximately 60 percent of those who participate in Friday’s congregational prayers and the imam who delivers the sermon on Fridays have a Turkish background. Recordings also took place inside Granville’s Masjid Noor as it may be the largest mosque in Sydney and the imam who delivers the Friday’s khutbah is Lebanese-Australian.

Mosques were also selected to be representative of the religious backgrounds of Muslim-Australians. Most Muslim-Australians follow the Sunni orientation of Islam and smaller numbers are Shi’ite. Accordingly, most of the mosques included in this study were of a Sunni orientation and only one, Auburn’s Ahl Albait Mosque, was of Shi’ite orientation. Smaller sects of Islam were not included. The socio-economic background of audiences and geographical positioning of the mosques were also considered in the selection process. Parramatta’s Marsden Street Mosque was chosen because it is in the central business district and visited by large numbers of professionals working in the area. The mosques selected for inclusion are based predominantly in western Sydney as that is where most of Sydney’s mosques are located.

Table 1: Characteristics of the selected mosques at Friday’s congressional prayers

* Percentage breakdown as approximated by the mosque administration

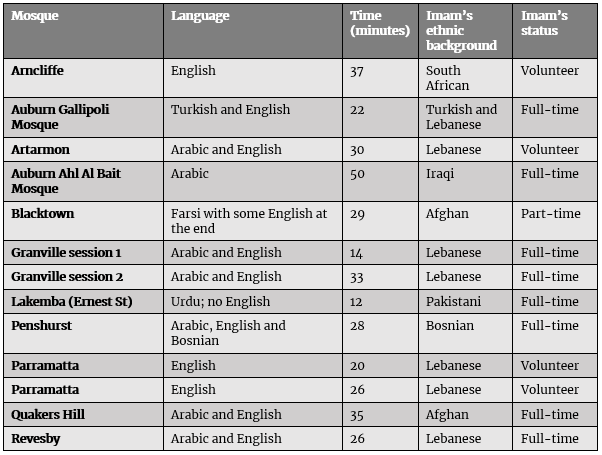

Characteristics of the imams who delivered the sermons

The imams who delivered the recorded sermons were from diverse backgrounds and characteristics (see Table 2). Most were full-time imams based at the mosque and responsible for running the educational aspects of the mosque and facilitating the religious rituals, such as the five daily prayers and Friday’s congregational prayers. On some occasions, volunteers from the community were called to lead the congregational prayers and perform the role of the imam. The sermon at Artarmon was, for example, delivered by Kayser Trad, the former president of the Australian Federation of Islamic Councils.

The imams who delivered the sermons were relatively young. Four were Australian-born, spoke fluent English and were between the ages of 28-30 at the time of the recording. Most imams were under the age of 50 and only one imam was above the age of 60.[1]

The sermons were mostly 20 to 50 minutes in length and delivered mostly in English. Some portions of the sermon, and in some cases the entire sermon, was delivered in a language other than English.

Table 2: Characteristics of the imams and their recorded sermons

General characteristics of the sermons

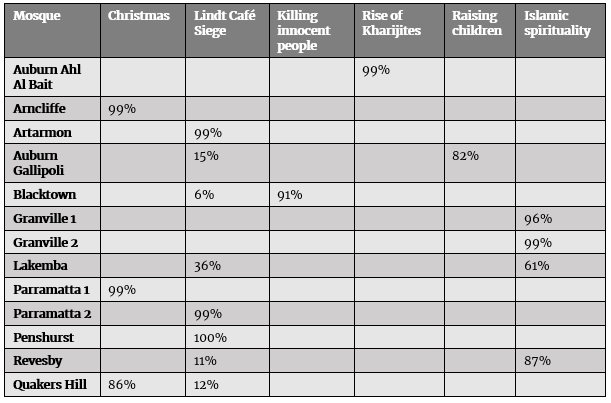

In addition to the Lindt Café Siege and Christmas, the topics covered in the recorded sermons included the consequences for killing innocent people, the rise of the Kharijites (a sect in Islam held responsible for killing the family of the Prophet Muhammad), raising children and aspects of Islamic spirituality, including thinking positively about God and the rewards and punishments for actions (Heaven and Hell). The extent to which each sermon focused on these topics is presented as percentages in Table 3.

Table 3: The extent of coverage of topic expressed as a percentage

The most widely discussed topic inside the mosques where the recordings were conducted was the Lindt Café Siege—as stated earlier, of the 14 recorded sermons, eight included the issue directly. This is not surprising given the incident occurred only a few days before and was directly relevant to the lives of Muslim-Australians. The extent to which the topic was covered varied, with some discussing it in more detail than others. The imams who delivered the sermons at Artarmon, Parramatta and Penshurst dedicated their entire sermon to discussing the topic. The imams who delivered their sermons at Auburn, Blacktown, Lakemba, Quakers Hill and Revesby dedicated a portion of their sermon to the topic. The imams at Arncliffe, Parramatta (S2) and Quakers Hill dedicated most of their sermon to the topic of Christmas.

The Lindt Café siege and encouragement to interact and engage

Of the imams who spoke about the Lindt Café Siege, the message communicated to audiences was that what had happened in the name of Islam was wrong. Five out of the eight imams who spoke directly about the issue condemned the attack and used terms such as ‘shock’, ‘horror’, ‘sadness’ and ‘tragedy’ to describe the incident. Three imams did not condemn the attack explicitly, but the purpose of their talk was indirectly aimed at condemning the attack. All imams communicated their disapproval of the attacker by siding with the victims who were frequently described as being ‘innocent’, a term that was used on 17 occasions.

Several key points ran across most sermons relating to the Lindt Café Siege. The first of those included condemnation for the attack and assertion that the violent attack did not have any Islamic justification. Some of the statements made by imams were:

‘We condemn such actions no matter if they happen here in Australia or overseas and we show our condolences for the families of all those who have died and lost their life’ – Parramatta session 2 imam.

‘We have all witnessed in Sydney what a certain person did, threatening the lives of innocent people; Islam condemns that’ – Revesby imam.

‘We offer our condolences to the people who have lost members of their family as a result of the incident’ – Quakers Hill imam.

‘No one who is following the teachings of Islam should do such things; we condemn such acts’ – Penshurst imam.

Emphasising that the attack does not have any Islamic justification, the imams said:

‘The killing of innocent people has no relationship with Islam’ – Revesby imam.

‘No one following the teachings of Islam should even consider doing these things, taking innocent people hostages; our religion does not teach us to be violent’ – Penshurst imam.

‘The killing of innocent people has no relationship with Islam’ – Lakemba imam.

‘Islam in no way shape or form approves or caters for chaos and anarchy’ – Auburn imam.

‘People are killing innocent people in the name of Islam. Islam defends people. Islam doesn’t take the life of innocent people’ – Blacktown imam.

‘Last week we witnessed an episode that desecrated the words “la ilaha il’Allah. It was an act of blasphemy desecrating these words and it was an act of criminality’ – Artarmon imam.

Further to the assertion that the victims were innocent, and Islam does not endorse killing innocent people, audiences were warned about the spiritual consequences of the act, including that they will be eternally damned and destined to burn in hellfire forever. The most often-repeated verses were ‘whoever kills a believer intentionally – his recompense is Hell, wherein he will abide eternally, and Allah has become angry with him and has cursed him and has prepared for him a great punishment’ (Qur’an 4:93) (Blacktown, Penshurst, Parramatta and Lakemba) and ‘whomsoever kills a soul and creates corruption on earth, it is as if he has killed all of humanity and whoever saves a soul, it is as if he has saved the whole mankind’ (Qur’an 5:32) (Auburn, Parramatta and Penshurst).

As it relates to the wider Australian society, Muslim-Australians have mostly been critical of the government and media’s misrepresentation of Islam and Muslims, but in this context, some imams praised the Australian media and government bodies for the way they responded to the incident. The sermons delivered at Parramatta and Artarmon, for example, praised the media for what they saw as fair and decent coverage of the incident and, along with it, the Australian public for starting the #illridewithyou social media campaign (to show support for Muslim-Australians on public transport):

‘Alhamdulillah (praise be to God), the media has been balanced and fair, which proves to us that Australian people are tolerant and good hearted’ – Parramatta session 1 imam.

‘Here we are in a nation where no one is being forced to leave their religion. We are living in a nation where when people saw a group harassing Muslims, quickly a group of Muslims said I will ride with you, I will support you. Quickly a group of people started a group called “Australians against Islamophobia”’ – Artarmon imam.

Imams also emphasised the need for compassion and tolerance toward non-Muslims. The imam at Artarmon emphasised, for example, that Islam teaches Muslims to live and act peacefully with non-Muslims. He referred to the example of Muhammad and the early generation of Muslim leaders, such as Khalid bin Walid and Umar Bin Khattab, who, according to the imam, dealt kindly and compassionately with non-Muslims in the early history of Islam. Non-Muslims, he emphasised, cannot be forced to convert to Islam and, if anyone was to do that, they would be committing a sin.

Directly in response to the Lindt Café Siege, audience members were encouraged to reach out and offer condolences to the victims and their families. The imams also asked their audiences to increase their knowledge of Islam, reach out to non-Muslims, and demonstrate through their actions that Islam is a peaceful religion and Muslims are peaceful people. The imam at Artarmon said, for example, ‘reach out and show them that we are the kind of people who pray for them and share our plate of curry or tabouli with them’. Muslims, the imams at Artarmon, Parramatta and Auburn emphasised, must represent their faith in the best way they can by following the teachings of Islam in their dealings with non-Muslims:

‘We need to be proactive. The word integration has a negative connotation, but let’s think of it in a different way; let’s think of it as interacting and contributing to society. You see the Muslim community, we speak to ourselves. We do not interact with the wider community and then we will stand and say, Islam is a religion of peace, Islam is this and Islam is that and we condemn this and we condemn that’ – Parramatta imam.

‘There is going to be some serious arguments, so arm yourself with knowledge. When you see the half verses, don’t comment, or make judgements. Go and read the verses and comment later, but say to these people, have you seen anything like that from me? This is the time to reach out because there are those who are stirring the pot and giving you the opportunity to correct people’s perception about Islam’ – Artarmon imam.

‘Let us represent Islam in the best way that we can’ – Auburn imam.

Christmas and the urge to isolate and disengage

Christmas is a time when most Christians celebrate the birth of Jesus, a man they consider to be the son of God. In recent times, some (including some sections of the Muslim community) take a secular interpretation of the event and participate in festivities such as the exchange of gifts with colleagues and friends and the erection of Christmas trees in largely secular settings such as shopping centres. Muslims refer to Jesus as Prophet Esa (pbuh) and believe he was sent to convey God’s message to humanity. Given Muslims also hold Jesus in high esteem, Christmas, as it became clear from the sermons delivered in Parramatta, Blacktown and Arncliffe, represents a time when imams feel the urge to convey to their audiences that Christmas is not an Islamic event and, despite their respect for Jesus (pbuh), Muslims must refrain from participating in festivities relating to Christmas and maintain their own identity.

To convey the point that Christmas is not an Islamic event, the imam at Arncliffe took the extreme position of questioning the legitimacy of 25 December being the date when Jesus was born. He argued the date of Jesus’ birthday is not known and Christmas is an event that dates to Roman paganistic traditions. According to the imam, the first Christian missionaries thought it would be easier for people to accept the new religion of Christianity if they were to hold a Christian feast on the date that Romans celebrated their gods. Therefore, they declared that Jesus was born on the day that Romans celebrated the birth of a pagan God referred to as the ‘unconquerable one’. Audiences were urged to refrain from celebrating Christmas and participating in activities relating to it. Christmas, according to the imam, contradicts core Islamic beliefs and a non-Muslim saying ‘Eid Mubarak’ to a Muslim is not the same as a Muslim saying ‘Merry Christmas’ to a non-Muslim.

The imam at Parramatta Mosque (S1) was also of the view that Muslims should not participate in Christmas celebrations. Jesus, he recognised, is a much-loved prophet in Islam. He mentioned that loving Jesus is an inclusive aspect of the Islamic faith, but that does not mean Muslims should become involved in Christmas celebrations and start exchanging gifts with non-Muslims. Islam, according to the imam, is a tolerant religion, but Muslims do not believe in Jesus as the son of God. Therefore, he argued that a Muslim contradicts their faith by celebrating Christmas.

‘We tell our young brothers and sisters that every religion has its own days of celebration. Every religion has their own holy days. The Buddhists have their holy days, but do the Muslims celebrate it – no. The position that we are finding ourselves in is that the Christians are celebrating their holy day and we must not engage in anything related to it because by celebrating, it is as though we agree with this idea of Esa (Jesus) being the Son of God…we do not believe in Christmas and we certainly do not believe that Jesus was the son of God’ – Parramatta session 1 imam.

The imam at Quakers Hill Mosque asked his audience not to imitate Christians in celebrating Christmas as it is not an inclusive aspect of the Islamic faith. Similar to the imam at Arncliffe Mosque, he emphasised that Muslims have only two occasions to celebrate, Eid al Fitr and Eid al Adha, and to celebrate Christmas is tantamount to deviation from Islam. Of the social gatherings related to Christmas, the imam made clear that Muslims should not say ‘merry Christmas’ to non-Muslims or attend festivities relating to the event. Parents were discouraged from providing resources or allowing their children to participate in Christmas celebrations.

From the evidence presented above, it is clear, as it relates to Christmas, imams strongly discouraged Muslims from interacting and engaging with members of the wider Australian community.

Making sense of the contradictions

A close examination of the sermons’ content revealed two main topics: the Lindt Café Siege and Christmas. In relation to the Lindt Café Siege, imams did not see any Islamic justification for the attack and encouraged their congregations to reach out and offer their condolences to the victims. They were also asked to increase their knowledge of Islam, interact and engage with members of the wider Australian society and demonstrate through their actions that Islam is a religion of peace. In this context, imams were found to propagate and promote interaction and engagement with the religious ‘other’.

However, in relation to the content of the sermons covering the topic of Christmas, imams depicted it to be an event that contradicts Islamic beliefs and practices. In this context, Muslims were discouraged from participating in the events and ceremonies.

Connecting the two contradictory messages conveyed by imams with the wider social and political discourses relating to Islam and Muslims, it can be argued the sermons relating to the Lindt Café Siege followed patterns found to be very common among some members of the Muslim community. In a political climate where violent acts are committed in the name of Islam, Muslims have been forced to take on a very active role in providing evidence through their positive engagement and interaction with non-Muslims that Islam is a religion of peace. However, the season of Christmas may create anxieties among some imams that, in the process of engaging and interacting with non-Muslims, Muslims will undermine and compromise their values, beliefs, practices and Islamic identities to fit in. As such, during the season of Christmas, in the interests of preserving the Muslim identity, imams may potentially be deterring Muslim-Australians from engaging with members of the wider Australian society.

Given that interaction between Muslims and non-Muslims is essential to reducing the prejudice and hostility felt towards Muslims, the advice that Muslims must not participate in Christmas-related festivities can be conceived as problematic. Nonetheless, Christmas is an annual event, and it is probable that outside the topic of Christmas, imams encourage their audiences to engage with members of the wider Australian community. Evidence of this can be seen in the content of the sermons relating to the Lindt café attack where audiences were urged to engage and interact with non-Muslims. Participation in Christmas-related activities is discouraged by the imams because they do not consider it to be an event related to the Islamic calendar and are concerned with the preservation and protection of Muslim identity.

[1] I had information about the names and ethnic backgrounds of the imams owing to my involvement in the Sydney and NSW Mosque Project.

Image: Lindt Cafe Memorial Martin Place, Sydney. Credit: Goran Has/Flickr.