Few migrant communities in contemporary Australian society evoke the same level of polarisation and contestation as those originating from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

Contrary to widespread belief, many of these predominantly Muslim communities settled in Australia well before Federation, albeit in much smaller numbers than today. Yet despite this long history of Muslims in Australia, and despite the significant contribution made to the building of contemporary Australia, recent studies about social cohesion and race relations, such as the Scanlon Social Cohesion Surveys, continue to show a persistent and comparatively high level of negative attitudes towards these communities in Australian society. Indeed, the 2019 findings, for example, show that “despite the optimism about multiculturalism, ‘negative’ or ‘very negative’ attitudes towards Muslims remain high”. In this is especially the case when compared to other faith communities in Australia with the level of negative attitudes towards Muslim Australians at times being four times higher. A number of other studies have had similar findings in relation to the disproportionate high level of anti-Muslim and anti-Islam attitudes prevalent in contemporary Australian society.

The nature of public discussion

In his seminal book ‘Orientalism’, published in 1978, post-colonial theorist Edward Said mad the point that long-standing prejudices intertwine with colonialist agendas to entrench oppression, subjugation and dispossession of ‘othered’ communities of the ‘Orient’. Said’s main argument is that the knowledge-creation process itself is an essential power instrument that can be employed to justify the oppression and subjugation of others. In this context, what is often circulated as either media and political discourse, or knowledge in academic and literary writing, has a critical role in how collective identities are represented; as well as in justifying how particular groups are (mist)treated.

In the specific context of Australia, many studies have examined how public discourse, in particular within mainstream media and political institutions, has exacerbated negative understandings of and attitudes towards MENA communities in Australia, particularly in relation to Muslims. This public discourse often reduces the heterogeneity of these communities to simplistic characterisations where one particular identity dimension, most often religion (i.e. Islam), is highlighted in ways that focus on tensions, fissures, even outright conflict. This is, of course, now even more prevalent in a context of rising far-right, populist ideologies that explicitly espouse anti-Islam political platforms. Such ideologies seek to dehumanise individuals and whole communities simply because of their race and religion.

This is the case even when Muslim communities are the target of terrorist attacks, as in the deadly attacks on Muslims at two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand in March 2019. These tragic events saw an unprecedented surge in online far-right extremism across the globe applauding the attacks, which left 51 people dead, as acts of heroism and legitimate defence against the ‘spread’ of Islam.

This reflects more a systematic circulation of Islamophobic discourses with a narrative of ‘invading’ and ‘multiplying’ Muslims that pose an existential threat to local Western societies. A recent illustrative example of this comes from the 2019 federal election campaign, when then far-right senator Fraser Anning posted a meme made by one of his team members to Facebook. The meme read, ‘If you want a Muslim for a neighbour, just vote Labor’, with an image of a visibly Muslim family with 11 children juxtaposed with a visibly Anglo-Celtic, three-child family holding the Australian flag—a continuation of the image of ‘undesirable’ Muslim neighbours being used as a powerful message for driving negative public attitudes towards all things Islam.

The rise of securitisation in the context of the so-called ‘global war on terror’ and its local policy manifestation, countering violent extremism strategies

The problem of negative public discourse about all things Islam and the Middle East is compounded by a banal conflation of religion and violence in ways that essentially link Islam and Muslims to global terrorism and domestic insecurity.

In recent years, the greater MENA region has been affected by numerous intersecting intra-state and inter-state conflicts, which have contributed to the further deterioration of the image of Islam and Muslims globally, including in Australia. The ongoing civil unrest in Iraq and Afghanistan was followed by a number of new conflicts associated with the 2011 Arab uprisings, which led to the eruption of the ongoing Syrian conflict, the Libyan civil war, the Yemeni conflict, and the ongoing Sudanese uprisings. Like other conflicts in the region before them, most notably the Lebanese civil war of the 1980s, these recent conflicts have led to increased migration flows from these areas, resulting in an increased perceived threat to national security and social cohesion, and further damaging the public perception of Islam and Muslim citizens living in Western countries, including Australia. These negative depictions rely on the Orientalist tendency to characterise Muslim individuals and communities as incapable of embracing democracy, modernity and human rights.

This situation is not helped when international political leaders perpetuate these sentiments, as illustrated most recently by French President Emmanuel Macron’s speech on the ‘crisis’ of Islam globally. This speech came two weeks before the shocking killing of a French teacher, Samuel Paty, for showing caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad. The perpetrator of this gruesome attack was an 18-year-old migrant of Chechen origin who had links to radical Islamist groups. And whilst French Muslims condemned the attack in unequivocal terms, they have nevertheless braced themselves for even greater levels of Islamophobia, driven by those who will use the tragic events to justify further marginalisation, racialisation and stigmatisation.

Sadly, Macron’s speech about Islam being in crisis globally and in need of reform reinforces the extremist views held by radical Islamists that they are being attacked for being adherents of Islam and that their activities are a form of self-defence rather than terrorism. All of this reflects the problematic and fragile relationship between French Muslims and the supposed French secularism, laïcité, which does not offer Muslims in France the possibility of nurturing hyphenated identities, as happens in many multicultural societies including Australia, Canada and the US. Worse still, this muscular version of secularism within French society views Muslims as inherently incapable of full integration; and indeed, as living parallel lives and pursuing a separatist agenda, as suggested by President Macron.

French domestic politics aside, the emergence of violent extremism internationally has had implications for Muslim communities in the West. Within Australia, terror attacks such as the Sydney café siege in 2014 and the Melbourne Bourke Street attack in 2018 damaged even further the already negative perception of Islam and Muslim communities. The political rhetoric and the media discussion about the events characterised them incorrectly as reflective of a deep theological schism and socio-political antagonism between Islam and the supposedly secular West.

The importance of such events is that they drive, shape and further direct public opinion and perception in relation to Islam and Muslims.

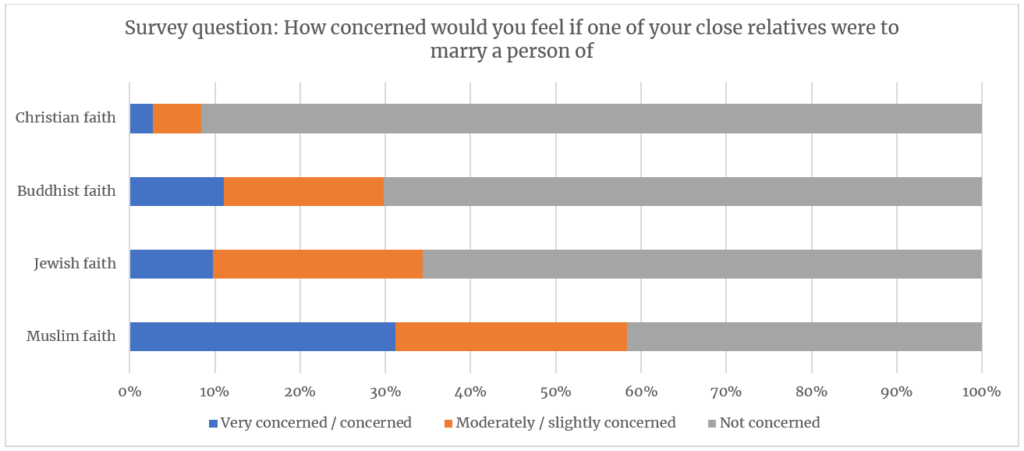

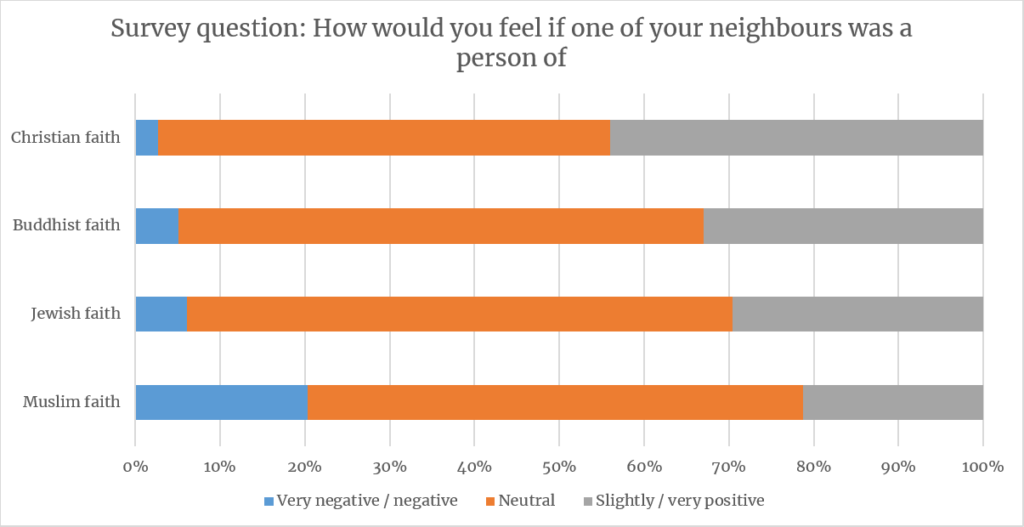

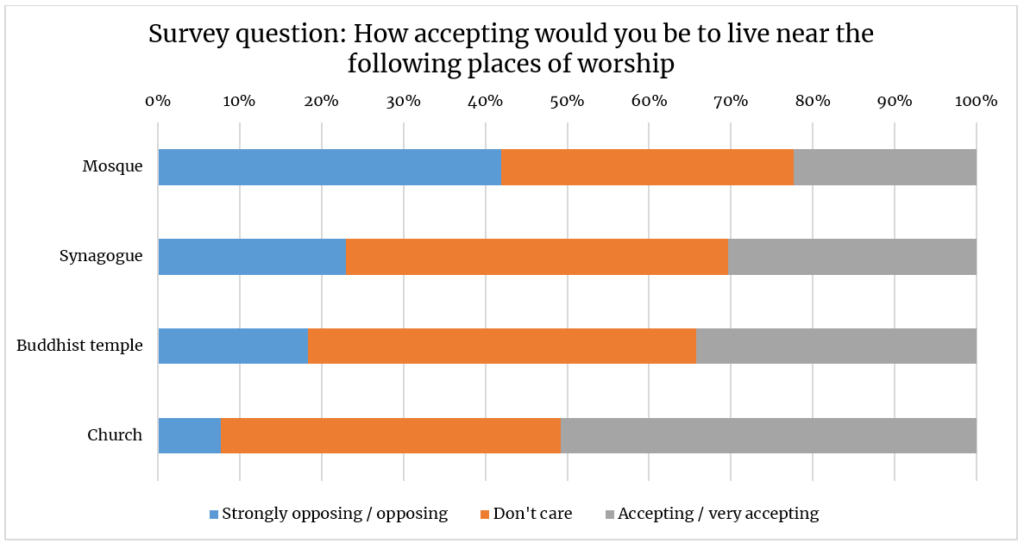

Many studies recently have shown how knowledge and social differentiation work in ways that can stigmatise, racialise and discriminate against MENA communities in particular those who identify as Muslims. Indeed, a study I conducted in 2017 into the relationship between different forms of knowledge of Islam and prejudice against Muslims in Australia confirms this negative trend, with respondents having the least factual knowledge about Islam being the ones who displayed the most prejudice. The study consisted of a national random online survey of Australians (N=1004) conducted through the Australian Survey of Social Attitudes. Three key items were tested to measure prejudice against Muslim Australians in comparison to other faith groups (see Figures 1–3).

Figure 1: Survey outcomes for assessing prejudice across the major faiths based on respondents’ feelings about a relative marrying a person of different major faiths

Figure 2: Survey outcomes for assessing prejudice across the major faiths based on respondents’ feelings about a neighbour being of different major faiths

Figure 3: Survey outcomes for assessing prejudice across the major faiths based on respondents’ feelings about living near a place of worship of different major faiths

The findings overall show a high level of rejection of and negative attitudes towards Muslims and Islam that cannot simply be explained by the supposed secular nature of Australian society.

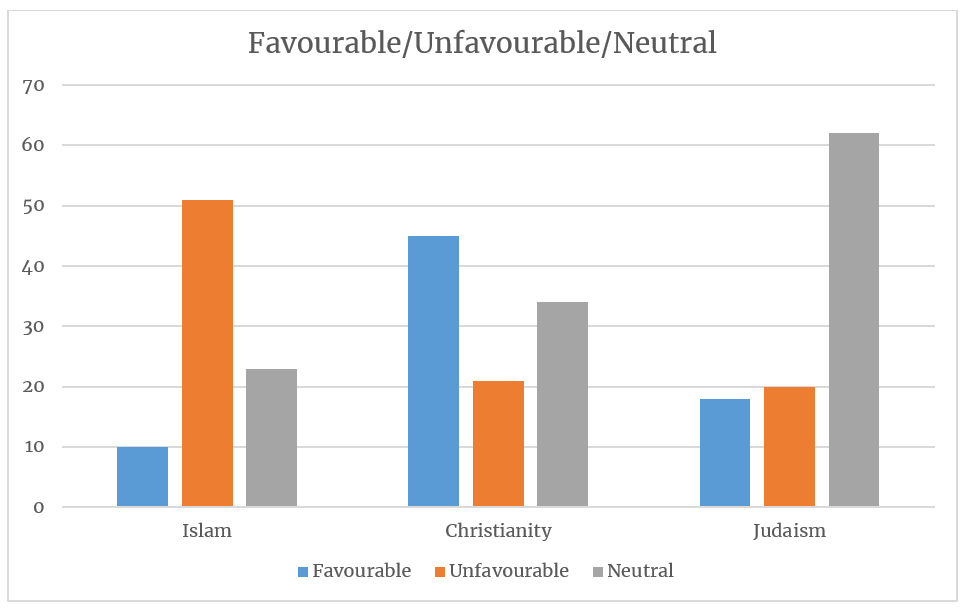

Indeed, in comparison with other religious groups, the level of negative attitude is disproportionately higher, indicating a deeper historical, as well as more contemporary, hostility and antagonism. Along similar lines, the recent global YouGov-Cambridge Globalism Project conducted online surveys of 1,006 Australians in 2019, in relation to their views towards immigration, religion, political institutions, and media, among other subjects. Survey findings show that more than half of the respondents (51 percent) viewed Islam unfavourably, as opposed to 10 percent who viewed it positively. The data, when cross-referenced with the other 22 countries surveyed, found Australians held among the most negative countries in regard to attitudes towards Islam (ranked 6th).

Figure 4: Selected data from YouGov 2019 survey of 1,006 Australians

Such negative attitudes cannot be regarded as part of a broader public backlash against diversity, nor a mere conservative hardening towards multiculturalism, where fear and suspicion of Australians with multiple ethnic and religious allegiances have become common practice. These persistent negative public attitudes towards Muslim Australians reveal a worrying normalisation and mainstreaming of Islamophobia. This normalisation is evident in its progression from a far-right fringe element of the (white) dominant society to a central position of ‘acceptability’ in the public domain, in particular within media and political discourse.

The effect of racialised public labels and fixed ‘research’ framings

The negative attitudes towards Islam and Muslim communities highlighted above are certainly linked to contemporary political events and broader politics of multiculturalism.

Yet, these negative perceptions and problematised identities are also reinforced as social categories that are pursued within institutionalised academic and research practice. Indeed, the last few decades have witnessed a surge in the study of all things Islam and Muslims, with sociological research in particular focused on the Islamic practices of Muslim migrants in Western cities.

In reflecting on the problems inherent in understanding and researching ‘othered’ groups that are ‘different’ from ‘us’, the late cultural theorist Stuart Hall wondered how best to represent people and places that are significantly different from ‘us’ and the reason ‘difference’ remains such a compelling and contested theme in the area of representation.

In relation to Muslims in the West more generally and in Australia specifically, much of the public and scholarly attention is driven by an underlying negative assumption around differentiated and irreconcilable collective identities. Socially constructed collective identities understand Muslim peoples’ values, religious doctrines, political attachments and cultural practices to be incompatible with mainstream norms and values. This increasingly problematised framing of Islam and Muslim citizens in Australia has contributed to the high levels of negative attitudes towards Muslim citizens in comparison to other ethnic and religious migrant groups. We have seen this trend in particular in the research areas such as countering violent extremism, Muslim youth social integration (or the lack of), the perennial question of the rights of Muslim women especially vis-à-vis their male counterparts, and the problems of reconciling values associated with Islam and Muslims with modernity, democracy and human rights.

Such questions are often dealt with in research agendas in ways that wittingly or unwittingly end up reinforcing pre-existing negative ideas about those being the focus of the analysis.

The argument here is not to stop studying religious minorities, including Muslims in Australia, nor is it to avoid altogether any social categories in academic analyses. Rather, we need clarity around the requisite epistemological conditions needed for studying complex phenomena in ethical, nuanced, and respectful ways.

In the context of Muslims in Australia, the aim is to avoid inadvertently reinforcing existing modes of cultural oppression and social exclusion. Indeed, much current research continues to be framed through a deficit-oriented lens that fails to empower socially oppressed groups and falls short of challenging existing forms of research agendas that, wittingly or unwittingly, end up perpetuating forms of oppression and discrimination.

A number of studies have shown that contrary to misinformation and Islamophobic discourses, there is nothing out of the ordinary about Muslim communities in the West in terms of practicing their faith authentically while being able to nurture local attachment, cross-cultural networking and inter-faith solidarity. The public discussion led by many political leaders, media and in some cases academics contribute to a situation where it is all too easy to vilify Muslims and construct them as potential threats to national security, and place them outside the circle of trustworthy citizenship. Current debates on the French, US and Australian models of religious accommodation have drawn attention to how majority religions are privileged even when religion is supposed to be relegated to the private sphere, as is the case with France, for example. This privileging masks majority religious bias and can lead to expressions of public hostility and anxiety towards Muslims and any expressions of their Islamic religiosity.

The situation in Australia, while markedly different and more hopeful than elsewhere, remains within a hyper-securitised national agenda, sees Muslims in general and MENA communities more specifically, characterised as the least desirable of migrants, who are viewed with more suspicion and apprehension.

Image: Harmony Day Australia, 2010. Credit: DIAC.