Australian universities largely promote Japanese language learning as critical for trade and ‘employability’, in a similar way to how other so-called ‘strategic’ Asian languages have been promoted by the Australian government over the last few decades.

The often-quoted definition of ‘employability’ by Professor Mantz Yorke, an expert in student experience in tertiary institutions, is:

We argue that there is a glaring gap between the instrumental ‘employability’ discourse of policy makers, media and university promotional texts; and actual motivations of Japanese language learners.

We also argue that Australian universities should play an important role in articulating the educational value of foreign language learning, beyond the ‘employability’ discourse. As Professor of Language and Literacy Education Joseph Lo Bianco aptly explains, language learning is ‘intimately linked to the essentially humanistic, cultural and intellectual reasons for making education compulsory’. Focusing on ‘employability’ undermines the role of higher education to intellectually challenge students and empowering them to be lifelong critical and reflective learners.

Foreign language education plays a unique role in the higher education sector. In a foreign language classroom, students of varied cultural and linguistic backgrounds meet and interact while learning a common language. Teachers take into account the cultural background of the students, make them aware of different perspectives in an intercultural space, and question existing stereotypes and attitudes that they take for granted. Learners need to think and behave based on the target language norms, and thus, they ‘reflect on self between the first language and the target language norms and [..] develop their sensitivity to others’ needs and a sense of empathy’.

The educational significance of learning a foreign language lies not only in acquiring communicative competence and knowledge of the culture and society where the target language is spoken, but also in the learners’ own self-transformation.

We, as applied linguists and Japanese language educators, working in the UK and Australia for the past 30 years, have witnessed a multitude of learners’ transformative experiences. But we have been consistently puzzled by the way Asian languages are depicted and promoted in Australia, and we realise that there is a huge gap between the value of foreign language education as we perceive it and the value communicated by policy makers, media and universities.

Policy makers and the media almost exclusively emphasise the ‘employability’ aspects of language learning

The 1987 National Policy on Languages, the first comprehensive national language policy in Australia, authored by Lo Bianco, valued the role of foreign languages in Australia’s linguistic diversity not only for national economic interests, but also for the interests and needs of Australian citizens, their unity and social harmony.

But since 1994, when the National Asian Languages and Studies in Australian Schools Program was launched, Asian languages have largely been portrayed as ‘trade languages’, a means whereby Australians can better access and benefit from the growing economies of Asia—particularly China, Indonesia, Japan and Korea—by learning their respective languages.

These ‘priority languages’ were deemed to be in the national interest and were included as such in the 2008 National Asian Languages and Studies in Schools Program. Although not a formal language policy in itself, the Federal Government’s 2012 White Paper ‘Australia in the Asian Century’ also encouraged the study of Asian languages and identified Chinese, Hindi, Indonesian and Japanese as priority languages.

The promotion of Asian languages has bipartisan support and Asian languages are playing a greater role in higher education than ever before. In June 2020, the federal government announced fee reductions for students in courses related to ‘expected employment growth and demand’ to ‘incentivise students to make more job-relevant choices. Languages are identified as job-relevant choices (as are teaching, nursing, clinical psychology and others), but other humanities and social science subjects are excluded from the scheme. Asian and other foreign languages are perceived to be important to meet industry demand; in other words, to increase students’ ‘employability’.

The mainstream media convey such narratives. Applied linguists Shannon Mason and John Hajek investigated the media coverage of language education at tertiary level in Australia between 2007-2016 (drawing on 57 newspaper articles in 12 different media outlets as their data set). They found that ‘the only benefit that is being communicated clearly to the wider population in our press sample is the economic rationale, but even more specifically that language skills are needed to engage with developing Asian economies’.

How Asian languages are portrayed in the mainstream press influences the public’s understanding of the value of language learning. Recent language policies and media portrayals of Asian languages have undermined the wider educational value of learning languages for individuals and communities. Not only that, there is a failure to differentiate between Asian languages, and the reasons students choose particular languages are ignored.

Motivators for learners of Japanese

Japanese is one of the most popular foreign languages in Australian tertiary institutions—in 2020 more than 20 universities offered Japanese language and studies courses. The number of students of Japanese language courses in tertiary institutions reached 11,353 in 2018 with majority of them being at beginners level.

There is little comprehensive data about the number of foreign language learners in tertiary institutions in Australia, but Year 12 enrolments by language in Australia between 2006-2019 show that Japanese, French and Chinese are equally popular, and each make up approximately 20 percent of Year 12 language enrolments. Numbers of Chinese language learners are consistently high, but the number of students of non-Chinese background is small. (Of note, international students from mainland China contribute to the sustainability of Asian language programs).

According to large-scale surveys conducted by the Japan Foundation in 2015 and 2018, Japanese learners are mainly motivated by personal and cultural interests in Japanese manga and anime, fashion, music, history, literature and art. Psychologists, Robert Gardner and Wallace Lambert, who published an influential book, Attitudes and Motivation in Second-Language-Learners, describe this type of motivation as ‘integrative’, which contrasts with ‘instrumental’ or economic motivations highlighted in national policies on Asian languages and the mainstream media. The Japan Foundation surveys found that instrumental motivations such as career development in business and trade were not the primary motivators. A recent study by Professor of Japanese Studies Chihiro Kinoshita Thomson also found that most tertiary students learn Japanese due to personal and cultural interest.

How tertiary institutions promote Japanese studies

We analysed promotional texts about Japanese language learning published by the universities affiliated with the Group of Eight (Go8), an alliance of Australia’s eight leading research universities. The Go8 is an influential voice in Australian higher education policy. All Go8 universities have comprehensive Japanese language and cultural studies subjects that contribute toward majors in both undergraduate and postgraduate degrees.

We searched for promotional text about Japanese language and studies on each university’s website using the keyword ‘Japanese’. Typically we were led to a page titled ‘Japanese studies’, ‘Japanese language’ or ‘Japanese language and studies’ where most of the public facing promotional texts were found and hyperlinks to further details, such as degree structures and individual subject information linking to the official university subject handbook. Individual subject outlines and assessment details were excluded from our investigations because they target current students, and are therefore less visible and prominent to the public.

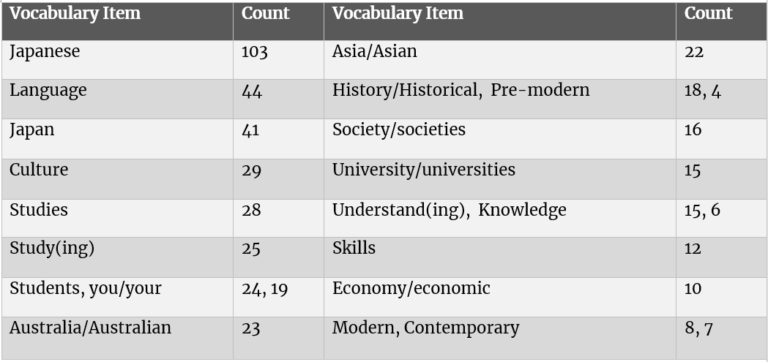

Public-facing promotional texts of Japanese language and studies amounting to approximately 2,400 words were identified. Frequently occurring words in university promotional texts and the content in which they are used reflect the way in which Japanese studies is promoted and give us an idea of how promotional texts for Japanese studies are typically constructed.

Table 1. Frequently occurring vocabulary items

Emphasising employability

These frequently occurring words capture a common promotional text which covers both ‘historical’ and ‘modern/contemporary’ aspects of the ‘Japanese language’, ‘culture’ and ‘society’ relevant to ‘Japanese Studies’. They become part of the ‘employability’ discourse when they are linked to employment opportunities. (In this study, individual universities are referred to as Uni. 1 through to Uni. 8.)

The word ‘study(ing)’ occurs 25 times in the promotional texts, most commonly in conjunction with one or more of ‘language/cultures/societies’ (13 times) such as in ‘studying Japanese language, culture and society means taking a significant step towards being Asia literate’ (Uni 2). The texts’ target audience, ‘students’ or ‘you’, are promised that they will ‘study’, ‘understand’ and gain ‘knowledge’ and ‘skills’. ‘Knowledge’ and ‘skills’ are depicted as outcomes, and portrayed as of generic applicability, enhancing the ‘employability’ discourse; students will obtain ‘knowledge’ and ‘skills’ to increase their employment opportunities.

‘Asia/Asian’ and ‘Australia/Australian’ occur in the context of positioning Japan in a geopolitical context, such as ‘Japan is one of the most dynamic nations in Asia’ (Uni 1), and ‘Japanese is the national language of Japan, a nation that is not only one of Australia’s major trading partners, but is also a country with which many young Australians have deep personal ties’ (Uni 4). References to ‘economy/economic’ occur when describing the significance of either Japan or Asia as Australia’s trade partner(s)—also supporting the ‘employability’ narrative.

The promotional texts represent an assumption that students’ investment of money and time will enable them to obtain ‘understanding’, ‘knowledge’, and ‘skills’ in relation to Japanese ‘language/cultures/societies’ all of which are necessary for them to secure future employment.

‘Students undertaking Japanese Studies will be able to access interesting employment opportunities domestically and abroad, in both government and commercial organisations.’ (Uni. 2)

‘Employers across business, government, the arts and various sectors actively recruit graduates who can demonstrate knowledge of and experience in Japan.’ (Uni. 4)

‘Your Japanese language skills and cultural knowledge will enhance your career prospects in Australia and abroad.’ (Uni. 5)

‘Graduates with a major in Japanese can find employment in federal and state government departments and private industry and community groups.’ (Uni. 6)

‘Graduates with Japanese skills work in diverse sectors, including business, education, interpreting and translation, engineering, government, law, media, diplomacy, journalism, IT, finance, tourism and hospitality.’ (Uni. 8)

Some universities refer to the significance of ‘intercultural learning’, beyond ‘employability’. ‘Study(ing)’ and ‘understanding’ tend to co-occur with one or more of ‘language/cultures/societies’ (eight times), for example, ‘understanding of Japanese language, culture and society in Australia’ (Uni 1). ‘Understanding’ also occurs in the context of intercultural learning (three times) which include, ‘in-depth understanding of cultural difference’ (Uni 3), ‘intercultural awareness and understanding’(Uni 8), and ‘mutual understanding between countries and peoples’ (Uni 8). ‘Knowledge’ also appears with one or more of the words ‘language/cultures/societies’, for example, ‘explicit knowledge of Japanese society and culture’ (Uni 8) and ‘cultural knowledge will enhance your career prospects in Australia and abroad’ (Uni 5). However, generally the context in which ‘understanding’, ‘knowledge’, and ‘skills’ are used suggest the promotional texts on the university websites reflect the ‘employability’, defined by Yorke.

The discourse of employability undermines the educational value of foreign language learning

Foreign language learning can be a life-changing opportunity and allows individuals to connect across borders. It also has a profound effect on one’s worldview and self-perception—as language learners we are invited to reflect on ourselves and our cultural identities in relation to the norms of the target language and its contrasting cultural values. Of equal importance, the experience of being a minority, as a learner of a foreign language, can positively influence one’s attitude towards foreigners and cosmopolitanism.

Well-known Australian scholar Fazal Rizvi puts the significance of intercultural learning beautifully:

‘Learning about others requires learning about ourselves. It implies a dialectical mode of thinking, which conceives cultural differences as neither absolute nor necessarily antagonistic, but deeply interconnected and relationally defined. It underscores the importance of understanding others both in their terms as well as ours, as a way of comprehending how both our representations are socially constituted.’

There is an opportunity for universities to promote an alternative discourse around language learning—a vehicle of personal growth and relational development that opens doors both inter-personally and inter-culturally.

Universities are already receiving large numbers of students who are motivated by cultural and personal interest who would be receptive to this narrative. Students primarily choose individual languages based on specific cultural features—they aren’t seeking generic economic opportunities. However, for the present, the dominant discourse of ‘Asian languages are for trade’ and employment is likely to be maintained by those who lack a nuanced perspective on the deeper sources of motivation that students have for studying Asian languages.

Foreign language learning can be a life-changing and transformational experience. It changes our view of the world and gives us the opportunity to meet new people who make us realise and question the norms and values that we have taken for granted. Universities need to communicate this educational significance, which can have a profound impact on students’ futures.

Authors: Dr Jun Ohashi & Hiroko Ohashi

Image: A multicultural group of students. Credit: COD Newroom/Flickr.