中文 (Chinese translation)

Chinese authorities have imposed a series of very significant restrictions on communities in both urban and rural areas since late January 2020, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our research team explored how Chinese people in rural areas have reacted. This was our focus because rural residents in China are estimated to earn only one-third of their urban counterparts, one of the highest urban–rural income differentials by international standards. This puts them at a disadvantage in terms of infection control and recovery.

A China-based member of our team conducted the first round of 16 face-to-face interviews of the province of Henan (which borders Hubei province in which the city of Wuhan is located) from May to June 2020, after domestic travel restrictions within China had been relaxed. Specifically, we wanted to document first-hand experiences of rural residents during the lockdown and their responses to the restrictions imposed on their daily lives. In August, with the support of a grant from the University of Melbourne, we scaled up the research by conducting 32 more interviews in four other villages: two in Henan and two in Hubei—the epicentre of the outbreak.

We encouraged interviewees to freely express their views in several ways: through anonymity; conducting the interviews in a relatively private setting (only family members, and no ‘outsiders’ other than the interviewer, were allowed to be present); asking open-ended questions and other measures. Further, we sampled respondents from different family structures, socioeconomic status, and villages.

Image: A patrol car in a Chinese village (not from one of the study sites).

Radical measures

Though Hubei and Henan have been two of the worst-hit provinces, there was no confirmed cases of infection within any of our case study villages. However, consistent with other studies’ findings, all villages were subject to road blocks, stay-at-home orders, bans on gatherings, video surveillance and forced quarantine of migrant workers who returned home (mostly to reunite with their family for the Chinese New Year).

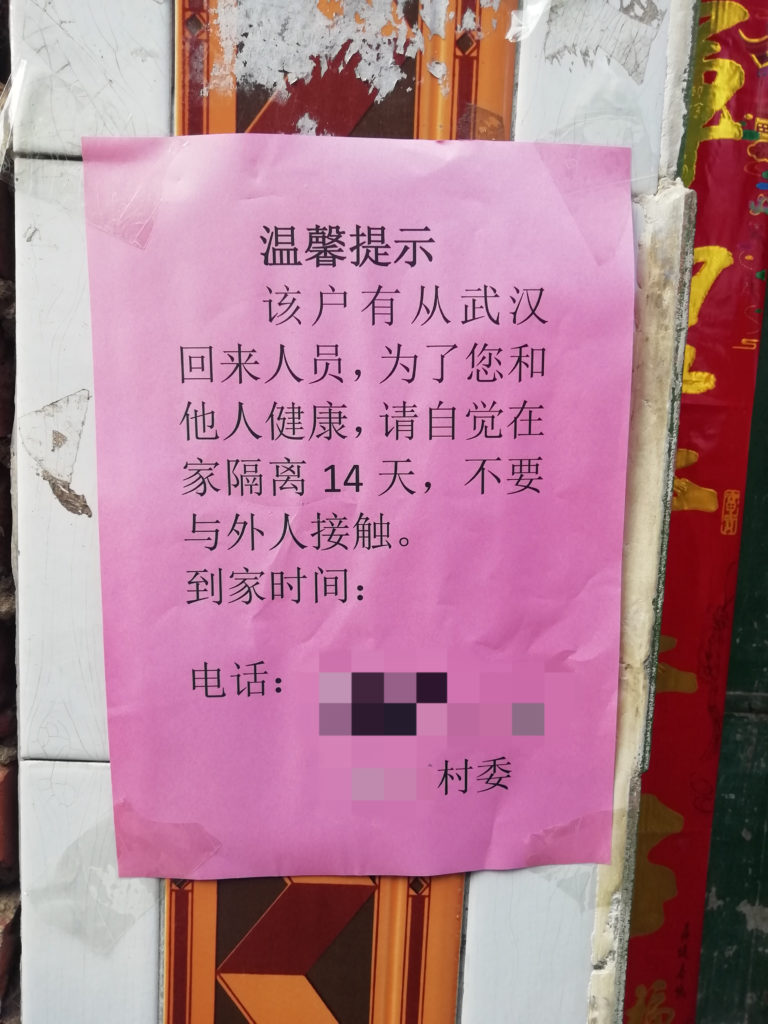

It was common that roads to villages’ main entrances were blocked by guards consisting of officials, village doctors, and volunteers. Mandatory quarantine was imposed on those who returned from Wuhan and other urban areas in Hubei before the Chinese New Year. Red banners or posters hung on the doors of households with individuals who were quarantining, urging people to avoid contact with them.

Image: A COVID-19 related poster warning people to stay away (not taken from one of the study sites).

Further, government officials and volunteers regularly patrolled the streets, sometimes in a patrol car, ordering people through loudspeakers to stay at home. In another village in Henan, which is small and next to urban areas, the entire village was under video surveillance cameras. During the lockdown period, anyone who left home would be warned through the village’s loudspeakers to return home immediately, and also criticised in local WeChat groups.

Village cadres and local volunteers were also involved in the organisation of the collective purchase of food and other essentials. In one village, for example, the village committee set up a WeChat group for residents to make orders from local stores and worked closely with local store owners and volunteers to organise the purchase and no-contact delivery of food and other essentials. When residents ordered something that the stores could not supply, the village committee would arrange a collective purchase once a day from markets in the closest township. In two other villages in Henan and Hubei, similar arrangements were made so that villagers did not need to leave their homes.

In one village in Hubei, a suspected case of COVID-19 at the beginning of the lockdown put the village under more pressure. In addition to the measures described above, the village committee also organised teams consisting of government officials and local volunteers to measure each individual’s body temperature—around 3,000 people in 834 homes—on a daily basis. It was only after 50 or 60 days that this measure was relaxed, and villagers were asked to measure their temperature themselves.

Overall, in all of the villages where we conducted research, infection control measures taken were disproportionate to the risks presented—mobility was highly restricted though there were no cases of COVID-19 infection.

Villagers’ attitudes

To understand villagers’ attitudes to the lockdown, we interviewed 36 villagers (six in each of the six case study villages) who stayed in their village from late January to April, and therefore all experienced the lockdown.

We found that the restrictive measures were largely accepted by local people, which is consistent with existing research that has suggested that citizen satisfaction with government measures is very high in China and that most rural residents are compliant. Our interviewees (including both village cadres and villagers) observed only a few cases of lockdown violations and reported that the villagers were generally calm and orderly. A few interviewees added that there was some resistance at the beginning, by individuals who found the lockdown inconvenient and were unwilling to follow the rules. However, after persuasion of the village committee members and frequently also their own family members, which typically emphasised the dangers of the virus, opposition waned.

In fact, our research indicates that the villagers’ relationships with their local leaders have become closer. In village WeChat groups, locals actively praised their leaders for what they said they regarded as their hard work. Some villagers offered help, for example, by providing vans for use by others, or to be drivers for collecting purchases. Some villagers even volunteered to send cash and gifts (such as bottled water, instant noodles, N95 masks and even private health insurance) to village leaders to express their gratitude.

“We appreciate what they [village cadres and local volunteers] did for us. They worked so hard, day and night.”

“I think the government did the right thing.”

“I can’t imagine how better the village government could have done their job.”

Even if there was also some discontent, the measures were deemed acceptable because ‘there was no choice’, and it was ‘for everybody’s benefit’, both of which were common responses from our interviewees. As one interviewee further elaborated:

“None of the measures were unnecessary … Although sometimes [I] felt that the village radio kept playing the same thing, sometimes several times a day, all to remind people how to prevent the disease and not to leave their home, which was annoying. But eventually that was for everybody’s benefit. Gradually people got used to that … so [we] can’t say that was unnecessary.”

Among all the interviewees, the most negative response was:

“I don’t think [the measures] were effective, but nor were they ineffective. We didn’t have any [COVID-19] cases from the beginning so I can’t judge.”

This response demonstrates a mild suspicion, which is far from clear opposition.

When discussing the underlying reasons for the positive response, we were struck by what seemed to be the strong emotional bond between the villagers and the Party-State. The villagers indicated a deep trust in the government’s commitment to their wellbeing. As one interviewee elaborated:

“You see, the central government has put considerable effort and made huge economic sacrifices, all to put this [pandemic] under control. Think about how much the country [central government] has done. What else can you say? The government is more worried than anybody!”

Another interviewee said:

“[The government] didn’t allow you to go out. This was for your benefit, to care for you, to take responsibility for the people … This is why China is great and how we have won [the fight with COVID-19].”

In the eyes of many, following lockdown rules was considered a way to contribute to the country. Many identified with a popular saying on the internet, ‘make contributions to the country by staying at home’. As one interviewee phrased it:

“We have all consciously participated in the prevention of the epidemic and have actively fought against it … In particular, staying at home is not only for our own benefit, but also for the country’s benefit. We are confident that the Party and the government will lead us to win this battle.”

Understanding the lockdown experiences in context

There are at least two factors that help explain this. On the one hand, alongside the ‘draconian’ measures, the village cadres and local volunteers delivered much-needed services to villagers, such as the delivery of food and other essentials. In addition, they were challenged by a new and extremely intense work schedule. The work in some cases put their own health under threat—conducting temperature checks of suspected cases and accompanying patients to hospitals, exposing them to the risk of becoming infected. This in part, explains why their work was very much recognised and praised by the villagers. The strong emotional tie between the villagers and the Party-State played a significant role in shaping the villagers’ attitudes.

By uncovering the micro-political views of rural residents within the messiness of everyday life, we can reach ground-level politics without relying only on interpretations of lockdown as a violation of rights, when this may be irrelevant to individuals and communities. As such, we endeavour to add value to the emerging evidence of Chinese responses to COVID-19—a critical documentation of the everyday voices from a range of positions, out of which new knowledge might be distilled.

Dr Xiao Tan (Asia Institute), Professor Mark Yaolin Wang (Asia Institute), Dr Yao Song (The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen), Associate Professor Tianyang Liu (Wuhan University).

Banner image: A COVID-19 related roadblock in a Chinese village (not one of the study sites).