New research indicates that levels of ‘trust’ in Large Language Models such as DeepSeek and ChatGPT among Chinese users is linked to national identity.

Within 10 years (by 2033) China’s artificial intelligence (AI) market is projected to have achieved a Compound Annual Growth rate of more than 33 percent, underscoring the sector’s rapid and strategic growth. This expansion is occurring alongside a growing emphasis in Chinese policy on data sovereignty, which mandates that data generated within national borders be stored, processed, and regulated within China. Supported by national strategies such as the New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan, AI is not merely positioned as an economic catalyst but as a key component of broader narratives around technological sovereignty and cultural renewal.

Most commentators have focused on macro-level dynamics such as policy, industry, and geopolitics, but few have looked into how Chinese people perceive AI and how their trust in these systems is shaped.

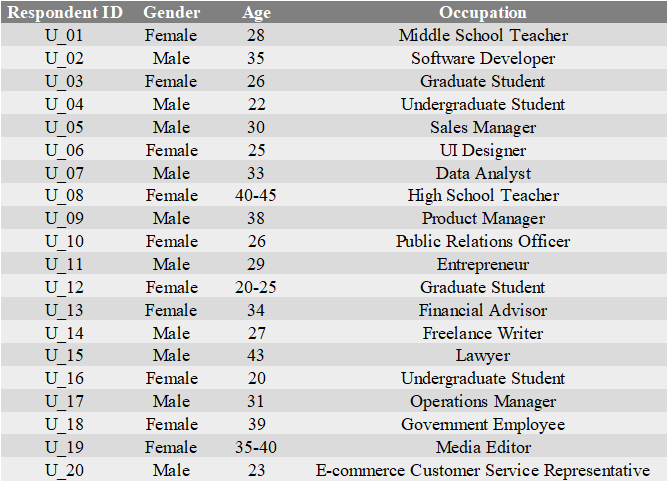

This study provides preliminary insights about how Chinese people perceive AI. It draws on 20 semi-structured interviews conducted in Shanghai between January and March 2025. Participants were recruited through a combination of community contacts and an online open call, and all were regular users of AI tools in their daily lives. Efforts were made to achieve balanced gender representation and ensure variation in occupational and social backgrounds. The final sample comprised office workers, students, small business owners, and other urban residents (see Table 1). While these interviews provide valuable insight into everyday AI use, the Shanghai-based sample inevitably places some boundaries on the breadth of perspectives captured, which should be kept in mind when interpreting the findings.

Table 1– Demographic profile and occupations of interviewed Chinese AI users.

AI preferences are never just about the technology

When asked which AI platforms they preferred to use, 17 out of 20 interviewees expressed a strong preference for Chinese-developed tools such as Doubao, DeepSeek, or ERNIE Bot over U.S.-developed platforms such as ChatGPT or Claude.

Their reasons were rarely technical, but rather a tendency to assign ‘national identity’ to artificial intelligence systems—an idea with profound geopolitical implications. It appeared that users were, consciously or not, attributing a form of ‘nationality’ to AI.

‘It’s not just about the language, one respondent told us. ‘Using a local AI feels more aligned with our values. I trust it more—it’s ‘ours’.’

This statement encapsulates a growing trend in China: the localisation of trust in AI systems, where data and algorithms become proxies for cultural and even constructing one’s sense of national belonging. In other words, what was once considered a universal tool is now becoming a nation building project related to patriotism, judged and embraced.

However, our analysis of the interviews suggests that individual’s reasons for choosing AI are not as simple as a preference for China-based systems. Beneath the surface, subtler rationales begin to emerge—the analysis uncovers layered and less visible motivations, pointing to deeper entanglements of trust, risk, and identity.

Data sovereignty and contextual trust

Data sovereignty generally refers to the principle that digital data is subject to the laws and governance structures of the nation where it is collected or stored. It has become a powerful political narrative shaping how citizens evaluate AI platforms, especially in contexts where concerns about cross-border data flows and geopolitical risk are heightened, which refers to the potential exposure of data to foreign state influence, surveillance, or regulatory conflicts.

Contextual trust, by contrast, highlights that trust in AI is not fixed but situational—users evaluate systems differently depending on political context, social stakes, and the perceived risks of disclosure. A ‘trust capital’ cannot be treated as an abstract and universal asset that may simply be transferred and used in new situations, because trust can only exist as something strongly contextualised and situation dependent. Empirical studies have confirmed this. One study shows that ‘domain knowledge and context critically influence whether users accept or verify AI outputs’ in applied computer vision systems. A systematic review further demonstrates that trust in AI evolves across cultural settings, emphasising dynamic trust formation and the cultural mediation of antecedents and consequences.

Many interviewees in this study explicitly referenced state-backed narratives about data safety. Some felt more secure using China-based AI tools because they believed the data would remain ‘within China,’ while others expressed distrust toward ‘foreign AI’ on the grounds that ‘you never know where your data goes.’

An office worker (female, 30s) in Pudong explained:

‘I don’t think foreign AI knows how to ‘speak Chinese’ in the deeper sense. It’s not only the words—it’s about understanding our society. When I use Doubao, I feel like it respects where I come from, and I prefer my data to stay inside the country. At least if something goes wrong, as a Chinese citizen I can seek protection and defend my rights. But if my data were leaked to the United States or another country, I wouldn’t even know which number to call or who to turn to for a complaint or legal remedy.’

For others, trust was situational rather than absolute. A graduate student (female, 20s) said:

‘ChatGPT is powerful, but who knows what happens with the data? Maybe it goes straight to the U.S. government. So I use DeepSeek. I’d rather my information stay here. But when I complain about things at my university, I trust ChatGPT more, because at least then the Chinese government won’t know what I said, and trouble won’t come to me.’

This apparent double standard illustrates that user trust in AI is not one-dimensional but shifts according to use context and perceived political risk. For tasks involving sensitive personal or institutional criticism, some interviewees inverted their trust logic—treating foreign AI, despite its data opacity, as a safer space for private expression.

Such responses highlight a paradox: the very systems framed as ‘unsafe’ become attractive because of their distance from Chinese state power. In other words, trust is not only about data flows but also about proximity to authority. Recent research confirms the context-sensitive nature of trust in AI, with trust levels often varying dramatically based on situational political or cultural cues—what some frame as trust dynamics shifting across domains. China-based AI is valued for procedural security (data sovereignty) yet distrusted for potential surveillance, while foreign AI is sometimes trusted as a channel for candid speech. This tension underscores that AI platforms are not just technical infrastructures but political intermediaries—their perceived reliability depends on how users map them onto regimes of power, censorship, and accountability.

Dual logic of digital trust and nationhood

The logic of digital trust operates along two intertwined dimensions. On the one hand, procedural trust refers to confidence in the governance structures, data-sovereignty protections, and regulatory compliance surrounding an AI system—China-based AI is often seen by its users as safer under this logic because it keeps data ‘at home’ and is embedded in familiar governance structures. On the other hand, epistemic trust concerns the perceived candour, completeness, and authenticity of AI outputs, encompassing users’ assessments of whether the system provides information that is reliable, credible, and substantively meaningful. Foreign platforms, despite being geopolitically distrusted, may sometimes be seen as more reliable precisely because they are distant from surveillance by Chinese authorities, which makes their responses appear more extensive and less subject to perceived ‘artificial’ reduction or Chinese-state regulatory filtering. Recent scholarship has shown that trust in AI is rarely singular but instead distributed across different risk logics, with users switching between models depending on whether they fear surveillance or deception. This dual logic is further reinforced by narratives of nationhood. Digital technologies increasingly serve as ‘carriers of national values’, where the choice to use China-based AI can signify loyalty and identity as much as technical preference. In this sense, trust in AI is not merely about technical performance or data flows, but about how users locate themselves within competing regimes of authority, belonging, and accountability.

A product manager (male, 30s) further underlined this situational trust:

‘I use DeepSeek for daily work, because I know it’s safer for company data. But if I want something more creative, I sometimes open ChatGPT. It depends on the context, but security always comes first.’

A university student (male, 20s) reflected:

‘Chinese AI is closer to our culture. But I don’t fully trust it either—sometimes it feels like it hides things or gives ‘official’ answers. That’s also a kind of risk.’

And for some, choosing local AI was about identity itself. A high school teacher (female, 40s) explained:

‘When I’m preparing lesson materials, I choose Doubao over ChatGPT—it feels like supporting our own team. … Even if the performance is similar, I feel proud that we have our own AI.’

These voices illustrate a dual logic of trust. On one hand, distrust of foreign AI often indexed anxieties about data outflow and cultural misalignment. On the other, trust in China-based AI rarely rested on claims of technical superiority; it was anchored in national belonging—albeit sometimes shaded by concerns about censorship and transparency.

This dynamic echoes Saskia Sassen’s diagnosis of the ‘denationalisation of global capital,’ now confronted by a re-nationalisation of digital trust. In a sense, AI is caught in the crossfire: built on global collaboration and open-source infrastructures yet increasingly expected to bear the alignment with national values and political imprint of the nation.

‘State filter’ critique: authenticity versus safety

Crucially, some respondents inverted the dominant pattern of trust. While most preferred China-based AI for reasons of data sovereignty, a few suggested that foreign AI offered a different kind of safety: freedom from local scrutiny.

Many interviewees noted that the types of questions they asked China-based AI differed significantly from those they posed to foreign AI. Certain topics, they felt, could only be raised with foreign models, where the interaction felt more comfortable and less constrained.

A lawyer (male, 40s) put it bluntly:

‘Domestic AI often feels like it’s wearing a cultural or political filter. On certain topics it speaks too carefully, like it’s smoothing everything out. If I ask a Chinese AI what shortcomings the Chinese government has, I only get these template-like, pre-set answers that never mention any real flaws. But if I pose the same question to ChatGPT, it will at least provide several specific criticisms. ChatGPT, at the very least, sounds closer to the real thing and therefore feels more trustworthy.’

Here, freedom from local scrutiny and authenticity become two sides of the same coin. For some users, Chinese AI ensures procedural safety by keeping data within national borders and processing outputs with domestic large language models—but this often comes at the cost of answers that appear mediated by a ‘state filter’, in which politically sensitive information is curtailed or reshaped. For others, ChatGPT may be unsafe from a personal data point of view but epistemically more reliable, precisely because it is seen as distant from Chinese state power. In practice, this paradox makes foreign AI function as a kind of digital refuge—a safer space for candid speech on sensitive or personal issues.

Describing domestic models as ‘filtered’ implies that alignment has been interpreted through the lens of national regulation. However, all frontier AI systems embed the normative assumptions, safety protocols, and legal constraints of their creators; foreign AIs are likewise ‘filtered’, aligned within Western legal and value-based regimes (for example, through ‘constitutional AI’). At the same time, it is broadly understood that China-based AI tools apply stricter content constraints on topics perceived as politically sensitive—particularly criticism of the CCP—in ways that U.S.-based AI tools typically do not. As a result, what feels ‘more real’ may simply be closer to the user’s preferred norms of candour, not necessarily closer to objective truth. Here, we analyse how Chinese users interpret these different alignments through their sense of proximity to particular authorities.

Three dynamics help explain why some users equate foreign AI with authenticity:

- Contextual integrity. When domestic AI answers too cautiously, users infer withholding—an inversion of contextual integrity, where conformity to local disclosure norms signals manipulation.

- Algorithmic authority by contrast. Directness in one model makes the other appear evasive, creating relational perceptions of candour and authority.

- Nationalisation by negation. Paradoxically, saying ‘ChatGPT feels more real’ is itself a way of nationalising AI: foreignness becomes a proxy for authenticity, much as the ‘spiral of silence’ shapes what can be voiced safely.

Perceptions of truth are mediated through state-aligned ideological frameworks, where the boundaries of acceptable knowledge are shaped by mechanisms of information control. The ways AI refuses to answer, avoids giving direct statements, or selectively cites sources become signals that users read as clues about political risk and authority. What some identify as filtering, others frame as responsibility; what some experience as candour, others regard as recklessness. In this sense, state ideology functions as the underlying grammar through which epistemic risk is assessed and trust in AI is ultimately negotiated.

Conclusion

The propensity to ascribe national identities to AI tools underscores that these technologies transcend their functional roles to become intricate cultural and political symbols. User preferences for particular AI extend beyond technical performance assessments to reflect deeper cultural alignments. These developments carry profound implications for the development, governance, and regulation of AI technologies.

Prospectively, the growing localisation of AI suggests that trust in these systems will be increasingly shaped by culturally specific understandings of nationhood. While such localisation can deepen the cultural relevance and social legitimacy of AI within particular contexts, it may also reinforce national boundaries and competing value frameworks. Rather than necessarily producing a more pluralistic digital future, this dynamic highlights a more complex trajectory—one in which AI becomes a site where different nations articulate, negotiate, or contest their cultural and political identities.

Authors: Chen Qu and Dr Wilfred Yang Wang.

Main image: AI-generated image illustrating user preferences between Chinese and other AI tools. Created with input from the authors. Credit: Doubao (A Chinese-developed AI Chatbot). An AI-generated image was selected to underscore the article’s focus on how people (i.e., the authors) interpret and interact with AI, and to avoid the cultural specificity or geographic anchoring that a real photograph of Shanghai would introduce. Using an AI-created visual also makes the representational process part of the argument, showing how AI itself participates in cultural meaning-making.