Why do students choose to study Arabic? Many university and government policies in Australia have framed language learning in terms of utilitarian ends, especially for employment. Promotional material often promises exclusive international job opportunities or unique skills to close a business deal.

But studies in Australia and other Western countries strongly indicate that students don’t primarily study Arabic for money, but for greater cultural understanding and interaction. This mismatch calls for a serious rethinking of how Arabic courses are designed and marketed.

The first part of this article looks at three relevant studies about the motivations of students from Australia, the US, and Scandinavia to study Arabic. The results, like others, show that people primarily learn Arabic for culture, people, politics and religion. Employment-related motivations are ranked much lower. The second part of the article attempts to re-imagine how Arabic could be taught in Australian universities. We suggest that there should be a stronger focus on the global, cosmopolitan, and civilisational elements of the Arabic language and Arabic literary culture.

Students are more interested in culture than in jobs

Mira El-Deeb’s Australian Study

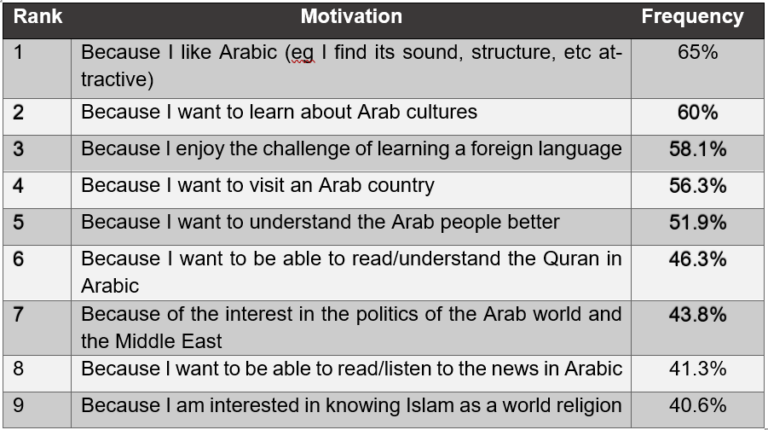

Mira El-Deeb, an experienced Arabic teacher and language pedagogy researcher, has done the most recent research based in Australia. She surveyed 160 students from seven institutions (two universities, three TAFEs, and two community organisations) in Melbourne, Australia’s second-largest city, in 2008 and 2009. Of those who participated, 58.1 per cent were neither Arab nor Muslim, indicating that Arabic has an appeal outside those communities that use it regularly. The participants could choose from 28 reasons they study Arabic or write their own reason. Here are their top reasons for studying Arabic:

Table 1 – Adapted from El-Deeb 2014 (p. 226)

El-Deeb’s survey shows that the top reasons for studying Arabic were an intrinsic love of Arabic or languages and a desire to gain a better understanding of Arabic culture, religion, politics, and people. Compare this to the results that are employment-related:

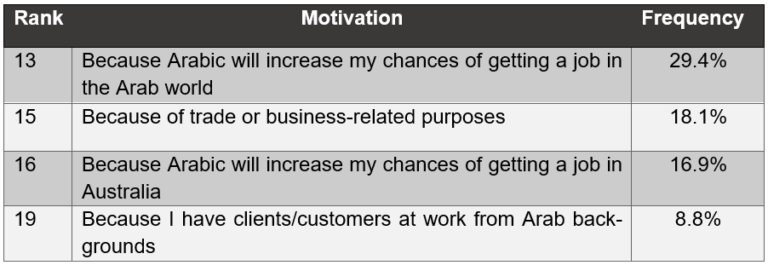

Table 2 – Adapted from El-Deeb 2014 (p. 226)

Only one-third of students studied Arabic to increase their job prospects overseas, and less than a fifth thought it was useful for trade or local job prospects.

Hezi Brosh’s US study

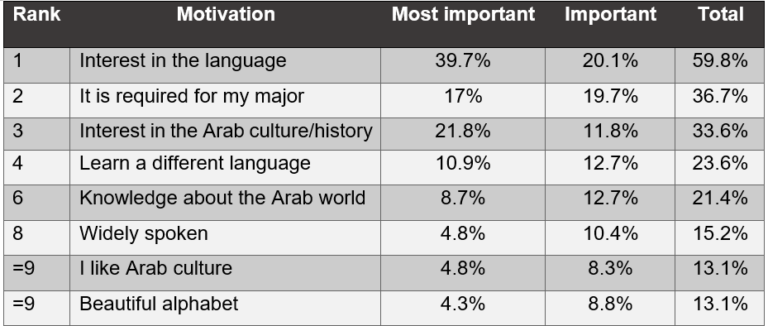

Hezi Brosh, a researcher and educator of Arabic, surveyed 229 students enrolled in Arabic classes in six colleges in the United States in 2013. The participants were given a list of 29 reasons to study Arabic, each reflecting a different kind of motivation. The respondents were asked to choose their top four reasons and rank them in order of importance from ‘most important’, ‘important’, ‘moderately important’ and ‘least important’. Brosh ranked the results based on the aggregate of ‘important’ and ‘most-important’. Here are the top options not dealing with employment:

Table 3 – Adapted from Brosh, 2013 (p. 33)

Brosh’s results show that the surveyed students are interested in Arabic itself or have a desire to be more knowledgeable about the culture and history of the Arab people. ‘Interest in the language’ was the only option chosen by more than half of the respondents as important or most important.

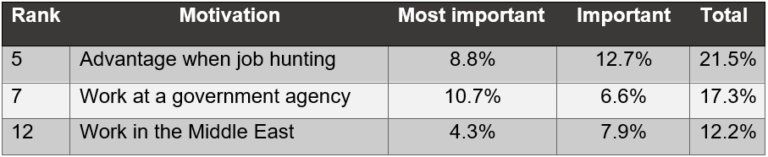

The percentage of people studying Arabic for employment is far lower:

Table 4 – Adapted from Brosh, 2013 (p. 33)

Raees Calafato’s Scandinavian study

Raees Calafato, Associate Professor at the University of South-Eastern Norway (USN), surveyed 96 Arabic learners in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark in his 2020 study. Despite being the most recent survey included here, the cultural differences between Australia and Scandinavia it make comparatively less relevant.

In all three Scandinavian countries, employment concerns were less important than cultural factors. Employment as a motivator to study Arabic was second last in Denmark, third last in Sweden, and fourth last in Norway. The Norwegians were more likely to study Arabic for work than the Swedes or the Danes. Despite this, the top four reasons across the three countries, to varying degrees, were: ‘I want to read in Arabic’, ‘I want to use it when I travel’, ‘I need it to understand global developments’, and ‘I want to watch media in Arabic’.

When given the opportunity to add their own reason, only 12 per cent mentioned reasons related to jobs. The top responses related to ‘religion, culture, history’ (20 per cent), ‘to interact with Arabs’ (17 per cent), ‘personal interest’ (16 per cent), and ‘socio-political reasons’ (12 per cent).

Implications of these studies

The above three studies show that employment is one of the weaker motivations for students to study Arabic in three different areas of the world. This inverts the prevailing emphasis on jobs over culture and invites us to recalibrate our focus. The cultural aspects should be given attention to match students’ interests. Students’ desires, orientations, and motivations should be put first in decisions related to the teaching of foreign languages. A student-centred approach will create stronger motivation among students and give students more options.

Arabic: A cosmopolitan world language

How could Australian universities present Arabic in a more compelling way? We argue that Arabic can be taught with a broader cultural scope that will draw greater interest from students and more accurately reflect the position of the Arabic language in the world. The Arabic language is an essential element to understanding Arabic culture, media, and literature and a gateway to understanding a global culture. The Arabic language has greater geographical spread, deeper historical roots and exerts more influence and power that transcends the borders of modern Arab countries. Looking at the Arabic language’s influence worldwide, we can see a different Arabic: a cosmopolitan world language, the lingua franca of the Islamic world, a classical language, a language of science, philosophy, literature, and the liturgical language of Islam. It is a language that forms a significant literary and intellectual stratum for much of Afro-Eurasia.

Arabic is uniquely placed to help diversify the Australian university curriculum for three reasons: it is global, cosmopolitan, and historically connected with the West. These three features discussed below call for establishing Global Arabic Studies, a field that uses the Arabic language as a lens to study cultures from across the world for more than a millennium.

1. A global language

Arabic has a truly global influence. It’s the only non-European language to be an official language in Africa, Asia, and Europe (Maltese is a variety of Arabic). Arabic literature, science and script have percolated through much of Afro-Eurasia. Take Africa as a case in point. The late scholar of Islam in Africa, John Hunwick, described Arabic as the ‘Latin of Africa’, where dozens of local languages are written using the Arabic script. In a recent article, historian Charles Stewart, an expert on West African manuscripts, explains how the Arabic (and Arabic-script) manuscripts of West Africa can help rebalance the narrative of world history away from Europe. The authors of this article have separately written about the importance of Arabic in Africa and Arabic as a global language.

This wide geographic spread means that Arabic an appeal to a wide audience and provide a great basis for diversity.

2. A cosmopolitan language

‘Cosmopolitan’ has varied usages and a long history. In this article, ‘cosmopolitan’ mean that Arabic written culture is a location for the meeting of many different peoples across time. Upon becoming proficient in the shared system of cultural expression, you enter a Republic of Letters, a community not based on lineage, space or time but on shared literary language and culture. This cosmopolitanism is the main characteristic of the Arabic culture that flourished around the Islamic world. The seeds of this cosmopolitanism were sowed in the spread of Islam. Within 100 years of the death of the Prophet Muhammad, people could travel from Cordoba in today’s Spain to Sindh in today’s Pakistan, entirely in lands where Arabic was the language that could transcend the local. It was the language of literature, politics, science, and religion. This brought hundreds of different identities, languages, and cultures into conflict, confrontation, and conversation in new ways. Arabic appeared as a bridge between many cultures synthesising disparate strands of knowledge and literary cultures. The hunger for knowledge created a translation movement that brought works from Greek, Syriac, Pahlavi, and other languages into Arabic. Arabic is at once local and familiar yet transportable and universal such that Arabic written in Minang, Lucknow, Timbuktu, Zanzibar, Kazan, Cordoba, Damascus, or Fez could be read by anyone in these places.

Arabic is a product of the interaction of many peoples, and each has left its mark on it. Such a language is ideal to broaden horizons and diversity curricula.

3. Historical connection to the West

Arabic’s proximity and connection to Europe means its influence on Western thought and civilisation is direct. This makes it ideal for diversifying an English-speaking university’s curriculum. The connection is wide: from literature and philosophy to science and engineering and agriculture and cuisine to trade and fashion.

One of the major achievements of this cosmopolitan culture was to form the institutions for knowledge to flourish. The university itself is based on the Islamic Madrasa, along with its ability to provide certification and degrees (ijazas). Arabic literary culture spread paper into West Asia, Africa, and Europe, a technology that entered the Muslim world from China in the ninth century. Paper, and Arabic book culture, passed onto Christian Europe through Islamic Spain in the thirteenth century. Also, the earliest instances of peer review are in Arabic learning, with the first known occurrence in a book by Ishaq b. Ali al-Ruhawi (d. 931).

Arabic was the pre-eminent language of science for 1,000 years from the Baghdad translation movement in the mid-eighth century until the eighteenth century. Astronomer Edmond Halley (of Halley’s comet fame) translated mathematical works from Arabic into Latin. Muslims synthesised Hellenic and Indian mathematics to give birth to a type of mathematics we recognise today (today we use ‘Arabic numerals’ to study ‘Algebra’). Early Muslim scientists (al-Kindi (d. 873), Jabir b. Hayyan (d. c. 806–816) and Ibn al-Haytham (d. 1040)) invented the method of experimentation. Arabic knowledge has profoundly affected philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, physics, medicine, pharmacology, agriculture, and irrigation. Arabic knowledge is part of the story of the world.

The point here is not to illicit praise or recognition from the West, nor is it to deny the West credit for its achievements. It is to show that the West is historically and inextricably intertwined with the Arabic literary world. It is not some foreign entity. This makes Arabic a natural way to broaden the curriculum in Australia.

Conclusion: unshackling Arabic

In this article, we’ve argued that Arabic language teaching in Australia should focus more on the culture and global impact of Arabic than its utilitarian value. Studies in Australia, the US, and Scandinavia show that students of the Arabic language are more motivated by the culture and impact of the Arabic language. By focusing on the global, cosmopolitan and civilisation aspects of Arabic we can help diversify and decolonise the university curriculum. For this to happen, Australian universities and the government must put aside their prejudices about the role of Arabic, and other languages, within the tertiary education system. Establishing a Global Arabic Studies outlook will enrich university curricula and boost enrolments. This process should be guided by up-to-date studies on student motivation and the current state of Arabic programs.

If the university’s role is to cultivate critical thinking and produce engaged citizens, then no other language can provide the historical and temporal reach and theoretical depth of Arabic.

Authors: Tarek Makhlouf and Dr Abdul-Samad Abdullah

Image credit: Rémi Mathis/Flickr.