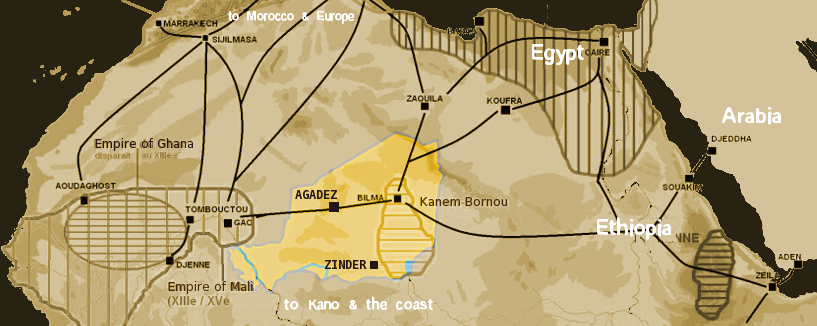

Islamic Arabic culture in the past extended to what is known as “Western Sudan”. In academic literature, “Western Sudan” refers to a large part of West Africa and, in this article, I will be using “West Africa” instead of “Western Sudan”. Associated with this extension were trade and commercial networks. Many historians emphasise the caravan trade routes that connected West Africa and Egypt, North Africa (modern Tunisia), and the far west.

Western Sudan and Interaction Networks through Trans-Saharan Trade Routes in 1400

Source: TL Miles/Wikipedia

Some of these trade routes may have been in operation well before the dawn of Islam in the 2nd century CE; but were abandoned for security reasons in the middle of the 3rd century. With the emergence of Islam and its spread into West Africa, the commercial relationships along these routes became primarily religious and cultural. This is evidenced by the alliance that was forged by the dynasty of the Almoravids and Ancient Ghana, several years after the kings of Ancient Ghana had converted to Islam; and this alliance succeeded in converting the ancient town of Tadmakka and Silla (in the Senegal valley, in the present day Mali) to Islam.

This religious relationship merged the Muslim peoples of West Africa into one nation that drew its way of life and moral values primarily from one source: Islam. The people of West Africa educated themselves about their religion and its language, Arabic.

As a result, the Muslims of West Africa became the intellectual elite of the region at the time. Government officials in pagan countries sought Muslim assistance in running their affairs. Muslims occupied key positions in translation and management in the then pagan Ghana Empire, before it became Islamic in 1076. This continued after the fall of the Ghana Empire and its replacement by the Islamic Mali Empire in the mid-13th century. Muslim Berber-Moroccan scholar and explorer Ibn Battuta (d.1369) described the zeal with which the people of West Africa taught their children about Islam and the Arabic language: ‘they placed a particular emphasis on memorising the Holy Quran, shackling their children if they show[ed] negligence in memorising it, the shackles removed only after they memorised it.’

The Islamic religious, cultural and political influences of West Africa were further entrenched by the famous pilgrimage of Mali’s Emperor Mansa Musa who was the ruler of the Mali Empire from 1312-1337, to Makkah in 1324. He brought large numbers of Islamic books and started the tradition of sending students from Mali to Islamic centres in North Africa for further education in Islamic studies. He commissioned the Spanish architect Abu Ishaq Ibrahim al-Sahili (d.1346) to design mosques and palaces.

Askia Muhammad I, who ruled the Songhay Empire from 1493 to 1528 and the first Askia who established the Askia dynasty (1493-1591), visited Cairo on his way to a pilgrimage in Makkah in 1496, asking the advice of great scholars of Cairo, such as al-Suyuti (d.1505), about the development of education in the region. Their advice had an effective role in developing education in West Africa. The subsequent Askias also did much to encourage education. Some of them had large libraries and added most of the new books and manuscripts that arrived in West Africa from Egypt and elsewhere to their collections.

The Sankore mosque which was founded in 989 and located in Timbuktu, which is situated in today’s Republic of Mali, developed into a flourishing centre of Arabic and Islamic education and became the favourite destination of students in West Africa. Subjects taught there included Maliki jurisprudence, Arabic syntax, morphology and rhetoric, logic, history, geography, astronomy, and arithmetic. The Arabic language was the language of culture and administration, as well as popular communication. Several towns in West Africa became cultural centres in the 14th century. Timbuktu and its institutions of higher education, such as the University of Sankore, was the ultimate goal for many scholars of the period 1307-1591, and many students aspired to be part of its learning groups and circles. Thus, along with its importance for trade, Timbuktu became a significant cultural centre and higher education hub.

Other important educational centres developed in Gao and Wallata (which both today form parts of Mali); and Kano and Katsina (which are today in Nigeria). Along with Timbuktu, these were the key Islamic cultural centres in West Africa during the period of the region’s Islamic intellectual history between the 14th and early 19th centuries. In addition to these centres, other sources of cultural dissemination—such as mosques, schools, and arbours—were built throughout the region. Schools were set up under trees and in scholars’ residences, and open spaces were used as primary schools, retreats, and prayer rooms. In this way, Islamic Arabic education flourished and continued excelling in the Songhay Empire during the reign of the Askia Dynasty.

The people of West Africa who embraced Islam from the 13th century also adopted the Arabic language in the urban centres of the region. This created a vigorous connection with Arabic culture, and the intellectual output of West Africa was deeply influenced by it. The intellectual achievements of the region’s prominent scholars and writers are testimony to the fine cultural output of the Muslims of West Africa, such as Ahmad Baba al-Timbukti (d. 1627) who wrote more than 40 books and left behind approximately 700 others. Likewise, later prolific writers such as Shaykh Othmān Ibn Fodiye (d. 1817), the members of his dynasty and many others are testament to the fine intellectual cultural output of the Muslims of West Africa. Most of the region’s intellectual output was in various Islamic disciplines and informed by the academic writing methods and styles that prevailed in North Africa and in the Arab Muslim world generally during that era. In the great cities, such as Timbuktu, Wallata, Kano, and Katsina, there developed a wide circle of scholars, thinkers, and judges who had mastered the Arabic language and Islamic thought. Their diverse works, in fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), hadith (traditions of Prophet Muhammad), tafsir (Qur’anic exegesis), Arabic grammar and morphology as well as history, followed the academic models that the Arab culture had developed in the Arabian Peninsula, Egypt, Levant and North Africa. The Arabic language flourished, and the people of West Africa not only mastered it but also produced innovative works of Arabic literature, including poetry.

The Songhay Empire fell in 1591 as a result of the invasion by the army of Moroccan Amir Ahmad al-Mansur. The invasion was resisted by the people of West Africa but led to the fragmentation of various integral parts of the empire, which sought to assert their independence. The most important centres of trade and intellectual activities in West Africa at that time, Gao, Timbuktu and Jenne, ‘came under a system of Moroccan indirect rule’ in 1591. The subsequent period saw a stagnation of the once flourishing Arabic and Islamic culture of this region. Most of the scholars of Timbuktu fled to Nigeria and settled in the city of Katsina. Many commentators consider the Arabic and Islamic intellectual products of this period as lacking in the eloquence and lucidity of earlier times. This intellectual decay affected the quality of the works of almost all Islamic disciplines, especially Arabic prose and poetry.

This period of stagnation in the 17th and 18th centuries was followed by a resurgence of Islamic Arabic culture during the reign of the dynasty of the Islamic reformer and revivalist, Shaykh Othmān Ibn Fodiye (d.1817) in the Sokoto Caliphate which was established and located in today’s Niger and Nigeria. This renaissance was manifested not only in Shaykh Othmān’s own writings, but also in those of his younger brother and senior vizier (chief minister), Shaykh Abdullah Ibn Fodiye (d. 1829); his son, Muhammad Bello (d. 1837) who was his second vizier and successor (d. 1837); and other writers of that Caliphate. Likewise, the Sokoto Caliphate also witnessed an Islamic political revival. Shaykh Othmān Ibn Fodiye endeavoured to set up an efficient administrative system that conformed to the earliest Islamic caliphate based in Madina and the later caliphates, and he made Arabic the official language of his caliphate. The efflorescence of the Arabic language went beyond technical writings into literature.

Islam’s cultural and political influences on West Africa continued to manifest heavily in the Arabic writings of the region during the Sokoto Caliphate (1754-1903). The Arabic literary tradition of West Africa still maintains a strong dialogue with Arabic-Islamic culture in the Arabian Peninsula, Middle East and North Africa. One of the most important mechanisms of this cultural dialogue is the production of important texts in traditional Islamic disciplines. Numerous writings of political leaders, viziers and scholars of the Sokoto Caliphate are examples of the resurgence of Arabic Islamic intellectual production. They wrote on a range of religious, social and scientific topics in Arabic and other languages. Most of these writers were also poets, composing poems in Arabic for an audience of intellectual elites, and in the vernacular languages using Arabic rhyme and metres for the consumption of the masses. Shaykh Abdullah Ibn Fodiye, Muhammad Bello, Muhammad Bukhari, Nana Asma’ daughter of Sheikh Othman, ‘Isa, Abd al-Qadir b. al-Mustafa for example were prolific poets who composed in Arabic, Fulfulde and sometimes in Hausa.

Unfortunately, commenting on the Arabic writings of West African Muslims of the time, some Western scholars have concluded that the literature was generally copious and unoriginal. This judgment ignores the nature and norms of Islamic writings in the Islamic peripheries outside West Africa during that period, whose understanding explains better West African Arabic writing.

The Arabic Jihad poems of the Sokoto Caliphate sought to create group cohesion by evoking and echoing concepts related to Islamic issues in the Qur’an and Hadith—such as the necessity of establishing justice, unity, resisting oppression, defending the weak and establishing a just and righteous community and society. The views of prominent Islamic scholars who are held in high esteem among Muslims on these matters are sometimes evoked as well. This aspect of West African Arabic poetry is under-studied despite the role Arabic poetry played in Islamic resistance activities in this region in general and, more specifically, in the Islamic Jihad in the Sokoto Caliphate. The West African Arabic poetry of this period particularly served as a medium of Islamic propaganda among Muslim elites to foster religious, social, and political change. The elite scholars in turn mobilised the public to support Islam and its socio-political agenda, which was exemplified by the Sokoto Jihad.

Regarding prose production, West African Arabic literature engages in a dialogue with foundational texts of Islam, Arabic literature in general, and other Arabic Islamic texts in the Arab Muslim world. This dialogue was manifested in forms such as quotations, citations, commentaries, and intertextuality to emphasise the legitimacy of what is seen as a global Islamic cultural identity. This phenomenon also aims to participate and contribute to the production of Islamic cultural and intellectual developments that consolidate an Islamic global sense of belonging and unity of purpose despite geographical diversity and ethnicity. Books authored by West African scholars such as Ahmad Baba al-Timbukti, Shaykh Othmān Ibn Fodiye and his brother Sheikh Abdullah and numerous scholars of Sokoto Caliphate are just a few examples.

With these glimpses of Islamic cultural and political influences in West Africa, it is unbelievable to see Margery Perham (d. 1982), a British historian of African affairs, writing about Africa in 1951: ‘Until the very recent penetration of Europe, the greater part of the continent was without a wheel, the plough or the transport animal; without stone houses or clothes; without writings and so without history.’ Perham’s statement could have been made out of ignorance, or was possibly a deliberate statement meant to serve the objectives of imperialists.

The brief exploration in this article of Islamic cultural and political influences in West Africa challenges colonialists’ views and narratives that portray the colonised in the way that justifies colonialism as enlightening and humanising. Perham’s statement, I believe, represents that kind of imperialist narrative and serves its purpose.

Recognition of Islamic cultural and political influences in West Africa and the role that the Islamic and Arabic literary traditions played in shaping the course of West African history had to wait until after the mid-1950s, the era of independence. Until then, one could only presume that there was a deliberate effort on the part of colonialists to suppress the important contributions that Islamic and Arabic literacy offered to sub-Saharan Africa as a whole, which could only be referred to as academic imperialism. It is interesting to see that the abovementioned recognition has led to the emergence of a group of Western scholars who could be considered the pioneers of objective Western scholarship on African history. The efforts and writings on West African history of the following scholars, among others, are notable: Nehemiah Levtzion, John Spencer Trimingham, Michael Crowder, Thomas Hodgkin, Peter Clarke, Mervin Heskett, Ivor Wilks, John Hunwick, and David Robinson. Hunwick’s tremendous efforts in helping with the preservation of West African Arabic manuscripts, besides his numerous writings on different aspects of West African Islam, is well recognised.

This is an area that remains understudied, and the nuances of the influence of Islam on West Africa at both the cultural and political levels have not been fully explored. The recent discovery of large quantities of Arabic manuscripts in various academic disciplines in Timbuktu, could lead to further insights regarding the cultural and political influences of Islam on West Africa. Rigorous study of these manuscripts may also foster understanding of the contemporary Islamic social and political dynamics in West Africa and Muslims’ endeavours in preserving and consolidating Islamic identity in the region.

Image: Sankore Mosque. Credit: Johannes Zielcke/Flickr (image has been cropped).