Major socio-economic and demographic changes in Singapore over the past decade have created a new political economy which has changed the state’s engagement with the transnational Chinese community at a time of globalisation and a rising China. I argue that Singapore aims to politically and socially integrate new Chinese diaspora (those who emigrated to Singapore since the early 1980s) into its multiracial society while capitalising on their transnational economic networks with China constitutes the main policy framework.

Singapore is an illuminating site for an analysis of the changing relationship between the state and transnationalism. It is the only country outside China with an ethnic Chinese majority in the population, and there are thriving and multifaceted linkages between the two nations. My analysis is situated in the broad literature of transnationalism, which is defined as ‘the processes by which immigrants forge and sustain multi-stranded social relations that link together their societies of origin and settlement…. An essential element of transnationalism is the multiplicity of involvements that transmigrants sustain in both home and host societies’.

Social and political transformation

The past decade has witnessed significant change in the social and political environment in Singapore which has in turn shaped the state’s engagement with the new diaspora in general. First was the 2011 General Election in which the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) won just 60.1 per cent of the popular vote, the lowest since the nation’s independence in 1965. The second major event was the demise of the founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew in March 2015, marking the end of an era in modern Singapore. The third was economic restructuring in which the nation has been more firmly geared toward internationalisation and innovation. All these events have a direct impact on the state-society relationship in the context of ethnicity, changing demographics, and transnationalism.

It was estimated that the number of first-time voters in the 2011 election was 200,000 and, together with other voters aged under 35, they numbered about 600,000 out of 2.3 million voters. Born after the mid-1980s, they grew up in a Singapore with an advanced economy and economic prosperity. Their views of the nation, its national and ethnic identities, and its future are different from the generation who lived in a much more difficult period after Singapore’s forced separation from Malaysia. As the younger generation has firmly established their national identity as Singaporeans, their perceptions of China and new Chinese migrants in the country are less accepting, which is partly driven by the English education environment they grew up with. According to the Census of Population 2020, the use of English as the language most frequently spoken at home among the resident population aged five years and older increased from 32.3 percent in 2010 to 48.3 per cent in 2020, while the use of Mandarin decreased from 35.6 percent to 29.9 percent during the same period. This situation has prompted some commentators to regard English as the nation’s new ‘mother tongue.’ This is the socio-linguistic mosaic in Singapore that the new Chinese diaspora have to live with (namely, not take Singapore’s ‘Chineseness’ for granted) and the Singapore government’s changing approach to nation-building.

New demographics

Singapore is rapidly becoming an ageing society with a chronically low fertility rate. In 2020, those aged 65 years and older increased to 17.6 percent of the resident population from 7.2 percent in 2000 and 10.4 percent in 2011. It is projected that 23.8 percent of the resident population will be aged 65 years and over in 2030. In the meantime, the past five decades have witnessed a steady decline of the fertility rate, which is now one of the lowest in the world: from 2.62 (1970–75), to 1.57 (1995–2000), to 1.16 (2017), and to a historic low of 1.1 (2020), which is far below the population replacement level of 2.1.

A liberal immigration policy thus constitutes an important component of the government’s population policy. Former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew believed that Singapore’s diminishing population would slow down the economy and regarded the task of increasing the country’s population as its ‘biggest challenge.’ Pointing to the stagnation of the Japanese economy as a result of the Japanese government’s hostility to immigrants, he put it bluntly: Like it or not, unless we have more babies, we need to accept immigrants.

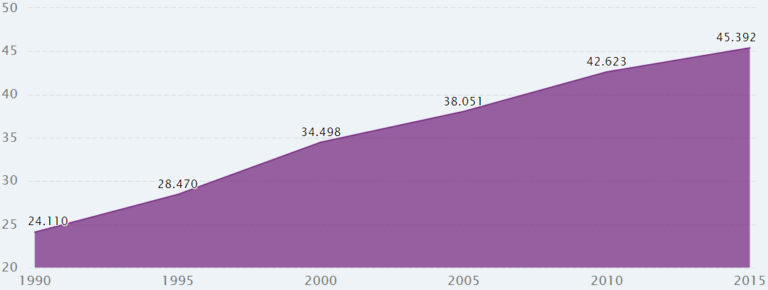

As a result of the government’s proactive initiatives in recruiting ‘foreign talents’ and a liberal immigration policy regime, the first decade of the 21st century had seen a rapid growth in the foreign permanent resident (PR) population. Singapore’s total population was 5.08 million in 2010 which increased to 5.68 ten years later. There were 4.04 million Singapore residents, comprising 3.52 million citizens and 521,000 permanent residents, and 1.64 million non-resident foreigners who were on various work permits or long-term visas. The number of international migrants to Singapore has increased rapidly, from 24 percent of the population in 1990 to 45 percent in 2015. According to United Nations data released in early 2020, the largest source of migrants (defined as naturalised citizens, permanent residents, and long-term work pass holders who were born outside of Singapore) came from Malaysia (44 percent of 2,155,653 in 2019, or 948,487 individuals), followed by those from mainland China (18 percent of total migrants, or 388,000 individuals).

Figure 1: Number of International Migrants to Singapore (1990-2015)

New Chinese immigrants to Singapore

While Singapore is a Chinese-majority nation, new Chinese immigration to Singapore is mainly a post-1990 phenomenon, facilitated by the establishment of diplomatic relations in the year. As mentioned earlier, beginning in the late 1980s, Singapore confronted two urgent challenges: The need for talent to keep its global economy competitive, and the need to deal with problems associated with its below-replenishment fertility rate. The state implemented a series of policies to address these challenges. First, the government would encourage and work closely with companies and recruitment agencies to recruit foreign talent. In 1988, for example, a Singapore government-sponsored delegation came to Los Angeles to set up a booth at a Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) hotel to interview potential job candidates for multinational corporations based in Singapore. Qualified candidates were offered jobs on the spot. ‘Contact Singapore’ was established in 1998 by the Prime Minister’s Office, administered by the Ministry of Manpower and later allied with the Economic Development Board, to serve as a ‘one-stop’ centre to assist highly skilled professionals and entrepreneurs to live and work in Singapore.

Second, the government would acquire foreign talent via its own educational system. Starting from the early 1990s, Singapore has used a combination of American-style programs taught in English and free or subsidised tuition to attract foreign students. It started offering full scholarship to high school students from China in 1992 to enrol in the local junior colleges and universities. It has also, perhaps more importantly, eased routes for permanent immigration after graduation to attract foreign students. For example, one of the main strings attached to some of the scholarships is that awardees must work in Singapore for six years upon graduation. A survey shows 74 percent of such students became permanent residents after completing their studies.

Third, the government would provide financial assistance and generous start-up funds to promote entrepreneurship among new immigrants. This strategy is also associated with the encouragement of mainland Chinese firms to list on the Singapore Exchange Mainboard.

As a result of deliberate policy intervention, the foreign permanent resident population represents the fastest-growing segment of Singaporean population. Although Singapore’s foreign talent initiative was not aimed at a particular ethnic group or nation, China has become a major source over the past three decades (second only to Malaysia), thanks in no small part to relaxation of China’s emigration controls and Singapore’s long-standing immigration history and its cultural and geographical proximity to China.

New Chinese diaspora emerged as a significant group in Singapore. They are not a homogenous entity but are composed of people of different socio-economic, regional, and sub-ethnic backgrounds. They are a highly selective lot: disproportionately well-educated with the majority holding post-graduate degrees from the United States, U.K, Japan, Australia, and other Western countries; they have ‘portable’ or ‘transferable’ job skills and work experience, and generally hold high-paying professional occupations, as the government applies stringent criteria in terms of applicants’ educational credentials and salary levels when granting permanent residency. According to the World Migration Report 2020, the number of migrants from China is 10.7 million. These new immigrants with portable skills are generally much better educated than the local population, and they are overrepresented in some research and higher education sectors. This reflects the deliberate policy of the government in recruiting foreign migrants who are categorised as highly skilled and low skilled. The former meet the nation’s drive towards the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution and low-skilled foreign laborers are needed for manual work that few Singaporeans want to do, and they have no prospect of settling down in Singapore due to policy restrictions.

The influx of large numbers of new (Chinese) migrants in Singapore created mixed public responses, including hostility and discontent among many Singaporeans, who have expressed their concern in newspapers, in parliament, and online. Not all the discontent is targeted at the new Chinese immigrants, but most is.

As I have demonstrated elsewhere, there are three different, but related, perceptions of them:

- Although of the same ethnicity and more or less of the same language as native Chinese Singaporeans, they are socially and culturally different;

- they compete with locals for jobs, education, housing, etc; and

- the newcomers, including those who are naturalised, are sentimentally and politically loyal to China.

These public perceptions differ significantly from the government’s policies, but they are also expressed, from time to time, in officially controlled news media like the Straits Times and Lianhe Zaobao.

The public discontent directed at migration issues were among the main reasons behind the ruling People’s Action Party’s worst performance in the 2011 General Election since the country’s independence in 1965. It received 60.1 percent of the popular vote while opposition parties won a ‘landmark gain.’ This watershed event in turn perpetuated a series of policy changes including popular nationalism. As historian Jason Lim puts it, ‘Popular nationalism is concerned about local issues concerning national identity, social cohesion, and an appreciation (or at least an understanding) of local heritage. Proponents of popular nationalism……view Singapore as a nation-state with a unique and evolving identity destabilised by a liberal immigration policy.’

The underlying logic of the ‘new diaspora’ policy framework

The development of the new Chinese diaspora has been significantly shaped by the Singapore government’s policies. The largest source of international migrants come from Malaysia, but this group does not have difficulty ‘integrating’ because the two countries have long-standing social, economic and cultural links dating back to the colonial period when both territories were under British rule. Indeed, they were united as one country for a short period of time before Singapore’s independence in 1965. Integration, therefore, focuses on the second largest source of international migrants, those from mainland China. The drive for greater integration is also a reflection of the government’s attempts to address public opposition to the growing numbers of migrants in the small island state, as already mentioned.

There are two main reasons behind the government’s position on the new diaspora. The first is economic and demographic—the need to attract foreigners with educational credentials and skillsets to facilitate the country’s economic transformation; and to help with Singapore’s declining fertility rate. The second is political and identity-driven—to ensure the newcomers are political loyal to Singapore (if they have naturalised to become Singapore citizens) and be closely integrated into the local multi-ethnic socio-cultural mosaic.

The two reasons have different priorities, and the government has given priority to the second over the past decade. As a young nation in the process of forming its own national identity, Singapore’s government wants to avoid any potential obstacles that might be detrimental to this larger and more important project. This is especially the case in relation to new migrants from China, a rising power with a long cultural tradition. Mounting US-China tension over the past decade has reinforced this policy preference in nation-building and strengthening a Singaporean identity. As Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong stated in June 2020, the existence of a significant number of ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia is a ‘politically sensitive issue’ and an ‘obstacle that would prevent China from taking over the security role currently played by the United States.’ He highlights specifically the delicate challenges faced by Singapore:

Singapore is the only Southeast Asian country whose multiracial population is majority ethnic Chinese. In fact, it is the only sovereign state in the world with such demographics other than China itself. But Singapore has made enormous efforts to build a multiracial national identity and not a Chinese one. And it has also been extremely careful to avoid doing anything that could be misperceived as allowing itself to be used as a cat’s-paw by China. For this reason, Singapore did not establish diplomatic relations with China until 1990, making it the final Southeast Asian country, except for Brunei, to do so.

Guided by these two key considerations, the Singapore government has formulated a series of policies towards the Chinese community in general, and new migrants in particular, with interconnected agendas. In 2015 at an event for the Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations (SFCCA), the then Deputy Prime Minister and Coordinating Minister for National Security, Teo Chee Hean, highlighted the role of the SFCCA: ‘First, a bridge between our people; second, a bridge between new and old; and third, a bridge between countries.’ The first role of the Chinese community, he said, was to enhance ‘multiracial society and multicultural traditions which are what ‘make Singapore unique.’ The second is to help the assimilation of ‘new immigrants into our society. SFCCA should continue to create opportunities for new immigrants to better understand Singapore’s customs and culture, and to deepen interactions. The third is for ‘a deep understanding of China and maintains many connections and networks in China.’

The formulation and strengthening of a unique Singaporean identity have been at the core of the state’s policies over the past decade. In celebrating Singapore’s bicentennial in 2019, Lee Hsien Loong spoke at length about the emergence and characteristics of this unique identity and tradition. He pointed out that before the arrival of the British in 1819, ‘Singapore had a long history that could be traced back to the 14th century’ which ‘made us quite different from our neighbours and friends.’ Further, he stated ‘Over two centuries, all these different strands wove together into a rich tapestry, a shared sense of destiny, and eventually a Singapore identity and nation’ but that nation-building is an on-going project: ‘[W]e are never done building Singapore. It is every generation’s duty to keep on building, for our children, and for our future.’

Integrating new Chinese migrants into Singapore’s multiracial society while engaging them for business networks with China has, therefore, become the overarching framework of the government’s position toward new Chinese migrants. In November 2016 at an event for the Singapore Hua Yuan Association, a major voluntary association representing new migrants from China, then Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office Chan Chun Sing (who also chaired the government’s Chinese Community Liaison Group at the time) noted that Chinese clan associations more than a bridge, they ‘are like a construction crane, with a solid foundation capable of rising and helping Singapore to reach out and connect with different parts of the world, not China alone.’ He emphasised that ‘the new Chinese immigrants must not only integrate with the older immigrants with their younger generations all Singapore-born, but also those from the minority races.’

In a similar vein, in March 2017 Chan spoke in the founding ceremony of the Singapore Jiangsu Association, another new migrants’ association saying: ‘New citizens are a part of our social fabric, and it is critical that they can integrate well and at the same time, contribute to society to ensure sustainable growth for Singapore. The Association will play an important and active role in facilitating and promoting social integration, thereby further strengthening the harmony and growth of Singapore.’ He urged the Jiangsu Association to ‘further promote exchanges and cooperation between Singapore and Jiangsu, as well as the whole of China, in areas such as trade, technology, culture and education.’

Community groups representing Chinese migrants in Singapore have publicly supported the government’s messages. In 2017, the Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations, a consortium of more than 300 locality/kinship associations, opened a Chinese Cultural Centre ‘to integrate newcomers to Singapore and showcase the local Chinese identity’, with Lee Hsien Loong as its patron. Its stated vision is ‘a vibrant Singapore Chinese culture, rooted in a cohesive, multi-racial society’, and its mission is to ‘nurture Singapore Chinese culture and enhance social harmony.’ The Singapore Hua Yuan Association has organised the New Migrants Outstanding Contribution Awards which focus on the awardees’ contribution to Singapore (the awards are open to non-Chinese). Another new migrants’ association, the Singapore Tianfu Association, has vowed that ‘Singapore is our home’ and that it aims to contribute to ‘our society and serving our country [Singapore]’ while maintaining links with China which have provided significant social and economic capital for its leadership and business members in their activities.

A vibrant force

In conclusion, significant changes have taken place in the past decade with respect to Singapore’s political economy and society.

The three interconnected forces behind the transformation of new Chinese diaspora are:

- the government’s policy, especially in terms of identity-building in a multi-racial Singapore and their role in contributing to the nation’s future economy through cross-border business networks;

- changing demographics and the growing number of new Chinese migrants in the nation; and

- the rise of China as the largest economy in Asia and its growing presence in Southeast Asia.

China also engages with its diaspora, welcoming diaspora investment in China and actively encouraging Chinese enterprises abroad in which Singapore has been one of the key destinations, especially in the context of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

The construction of Singapore’s national identity is a key focus of government in relation to Chinese migrants. Also key, are economic imperatives such as population growth in a country that is facing the dual challenges of declining fertility rate and a rapidly ageing society. The Chinese diaspora are a vibrant force in business transnationalism between China and Singapore, a nation which has made internationalisation one of its fundamental economic strategies since the mid-2010s.

Hong Liu Tan Lark Sye Chair Professor of Public Policy and Global Affairs, School of Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. LiuHong@ntu.edu.sg. ORCID-0000-0003-3328-8429

Main image: Singapore National Day parade. Credit: Jeffery Wong/Flickr.