Over a year into the COVID-19 crisis, questions linger about the social, economic, and political repercussions of the pandemic on the Arab world. To this end, we suggest moving beyond reactive and defensive responses to the virus to consider how crises can provoke dramatic moments of awakening to negative aspects of modernisation, such as capitalism, statism, and technological ‘progress’ that do not always improve the quality, freedom, and dignity of human life. Intellectual and practical implications ensue from the questioning that comes to the fore on the unequal burden-sharing of the downsides of ‘progress’.

The pandemic is engendering a kind of reflexive identity. This article attempts to consider how this reflexivity may develop and what its substance may look like in the context of COVID-19 within the Arab world.

The importance of the theory of ‘risk society’

Well-known sociologists Ulrich Beck and Anthony Giddens’ concept of ‘risk society’ is a critical approach to modernisation and capitalism, which, in looking at the underside of economic, political, technological, scientific ‘progress’ gives rise to reflexivity. Beck’s notion of ‘reflexive modernisation’ underscores a moral agenda, which remains unfulfilled in the Arab world due to the persistence of inequity and discrimination.

We seek to dwell in this moment of reflexivity before us. This takes us a step back from the immediate demands and challenges of the COVID-19 epidemic, such as infection and mortality rates, quarantine, unemployment, and access to vaccines. Instead, we consider questions of inequality and human rights—hoping to spur debate. Researchers can thus flag important issues for policymakers, in rising to the challenge of pandemic-related ‘risks’.

We undertake this brief exploration of Arab risk society and the potential for reflexivity with two assumptions. First, vulnerability to crises, in this case, a global pandemic, in Arab states has been structural. Second, the distribution of burden is unequal. Post-colonial state-building, and the economic, bureaucratic, and political structures that came with it perpetuated inequality, within and between Arab states and societies. COVID-19 has not created problems of marginalisation, political exclusion, or other human rights transgressions. Rather, it has made existing problems more pronounced. It has highlighted and laid bare trenchant predicaments in the ‘who gets what, when, and how?’ in the lives and experiences of millions across the Arab geography.

Inequality in healthcare

In the Arab world, inequalities and power asymmetries manifest themselves partly in unequal access to healthcare. The 2019 UN Human Development Report made an explicit link between power and inequality. Neoliberal economic policies and an emphasis on individual rather than collective rights exacerbate how social policies shape people’s health across countries and within them. The Arab world is no exception to this trend.

Problems of inequitable access and weak capacity for healthcare provision and lagging public health outcomes are arguably intertwined with the global capitalist system. The skewed distribution of power and resources that international economic structures generate are important to keep in mind. Entrenched inequality and an uneven distribution of the health burden is a moral question. It should concern not just national Arab elites, but also global economic and political power holders and policymakers. COVID-19 may afflict without discrimination, but not all polities, economies and societies can equally withstand its damage and rebuild in its aftermath. That is no coincidence. Social or distributive justice, from Algeria to Yemen, Libya to Palestine and Syria to Tunisia, is not a solely local matter. The interconnections between local, regional, and global inequalities loom large. Honest reflection is in order.

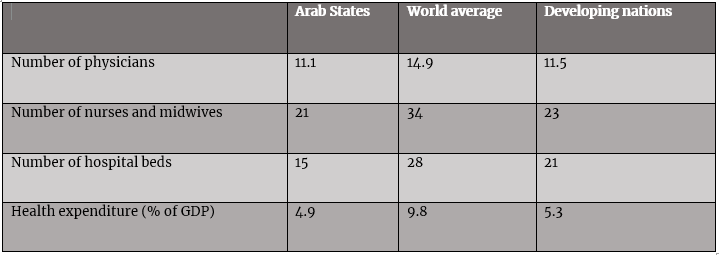

A UNDP report assessed Arab health rankings through quantitative indicators early on in the pandemic. These numbers, that flag the extent to which countries are prepared to take on COVID-19 according to the UNDP, give us some idea of where Arab states stand regionally and globally. The numbers of physicians, nurses and hospital beds, and spending on healthcare, are telling. According to these indicators, the Arab world trails Europe, as well as regions such as Latin America and the Caribbean.

*Figures per 100,000 people. Source: UNDP

Inequality-within-inequality

Compared to other regions, the Arab world has been struggling to meet the healthcare demands of the pandemic. In addition, within the Arab periphery exist populations and regions that are more marginalised than others. Not all residents and citizens within Arab countries enjoy equal opportunities in relation to healthcare.

Tunisia is one example of how disparities in income, employment and health correlate with one another. These have magnified over the past year, through economic and social impact wrought by COVID-19. As the Arab world’s first nascent democracy, the small north African country is particularly significant. It has been a tumultuous decade since Tunisians ousted dictator Ben Ali in 2011, as they cried for freedom, dignity and social justice. That many of the socio-economic grievances remain, or are worse in 2021 than in 2010, is very concerning. One study by a Tunisian rights group and advocacy center notes that lockdown measures (curfews, closure of businesses, etc.) result in unequal outcomes: the marginalised and ‘fragile’ in Tunisia experience lockdown differently. The life expectancy and overall health of groups living in poverty and deprivation is already compromised relative to the rest of the population. An inability to earn one’s daily bite to eat, cramped living arrangements, interruption to education in households where parents may be ill-equipped to home-school children, and more pronounced domestic violence against women have all been cause for concern. These issues raise the cost of lockdown measures for some sectors of the population less equipped to withstand them than their more affluent compatriots. Higher poverty rates in the interior and south of the country reflect the regionally-manifested ‘multiple marginalisation’ in Tunisia. This pattern also features in other Arab countries.

It is therefore no surprise that as COVID-19 unfolded, neighboring countries displayed similar regional disparities in healthcare provision. Spatialised inequalities rose more clearly to the surface. Morocco has a sharp rural-urban divide. Algeria, where an estimated 80 percent of hospitals are located in the country’s northern provinces, is another example. Other types of inequalities and structural vulnerabilities abound. Migrant workers in the Gulf states, on whose cheap labor rentier economies depend, have been particularly susceptible to COVID-19 and its economic blows. This has prompted outcry from human rights groups. In other Arab countries, violent conflict has stretched on for years, further destabilising already weak health infrastructure. Bombing, for instance by the Russians, has repeatedly targeted medical infrastructure in Syria and displacement puts further strain on both public and communal healthcare.

Time for reflexivity

Inequalities and vulnerabilities heightened by COVID-19 demand reflexivity and constructive policy critique. Conflict settings, for instance, cry for attention: Libya, Syria, Yemen, and occupied Palestine. Special policies and interventions are in order for such conflict-ridden locales. The fragility of the state and its social institutions amplifies risks to health and life. Huge refugee or displaced populations create additional challenges in access to aid and COVID-19 vaccines. How can policymakers, activists, and scholars ensure that those living through the ravages of war are not left behind? This is a hugely difficult challenge even in countries on the cusp of ‘post-conflict’ reconstruction, such as Libya.

Further, we see a ‘return of the state’ across the Arab world. There is a huge price to pay for this revitalised state-ness. We witness rollbacks of newly acquired individual democratic freedoms for individuals (e.g. in Tunisia), the deployment of the army, surveillance, lockdowns, shutdowns, and categorisations of human beings created along age lines, sickness/health delineations, and the probability that vaccines will be more available to those with means—raising questions of equity. Individual and institutional advocates of democracy stress that it is not only authoritarian states who have abused emergency powers, curbed free speech, and circumvented the rule of law in the COVID-era. Democratic governments may engage in similar curbing of freedoms, as the ‘Call to Defend Democracy’ cautioned last year. Other advocacy groups, such as the International Center for Not for Profit Law, have been monitoring emergency laws that detract from human rights and civic freedoms across the world. In the name of ‘biosecurity’, imposed hotel quarantine even for citizens traveling back to Australia and bans on holiday travel in the UK are some examples where established democracies have been curtailing basic freedoms related to mobility, for instance.

In the Arab world, COVID-related measures over the past year all bode ill for the freedoms desperately demanded by publics and willfully curtailed by political elites, who seem eager to pounce on the opportunity to militarise and securitise. In our view, using the pandemic to strengthen the state is at the expense of society and threatens already feeble protection of human rights in the region. Governments have limited freedom of speech and movement, declared and/or extended states of emergency, used excessive force to impose lockdowns and curfews, and imposed electronic/drone surveillance—all presumably to combat the pandemic. It is as though states are reclaiming whatever ‘space’ (public or private) society wrested from them during and since the 2011 ‘Arab Spring.’

In considering the full gamut of socio-economic and political ‘risks’ brought to the fore by COVID-19, the pandemic crisis, we contend, invites reflexivity. That is, the ownership of problems, by responsible citizens who earn the freedom to self-empower and self-govern. Beck suggests a collective responsibility in risk society. There is potential for transforming the burdens of the pandemic, including the new forms of ‘governmentality’ it has inaugurated, into opportunities to limit centralised interventions and intrusiveness. Newly devised instruments of French philosopher Michael Foucault’s ‘biopower’, control over living populations, flourish. Mandated social distancing, surveillance, testing and tracking of those who (might) carry the disease, vaccination requirements, and travel restrictions are some examples.

Active, aware, and engaged citizens (even in authoritarian contexts, albeit at greater danger), can thus be the bottom-up, agentic side of ‘reflexivity’. However, political elites too must engage in self-critique to recalibrate their discourses and policies. They should take heed and exploit this reflexive moment. Otherwise, deepening inequality threatens people’s health as well as governance and weak legitimacy beleaguering Arab states.

To this end, the dialogic ethos of German philosopher Jürgen Habermas’ communicative action is relevant to grappling with normative issues related to social change. It highlights the place of language and deliberation in shifting the focus of power from the state to society. This can complement Beck’s reflexivity and attendant pursuits of critically, justly, and practically reconfiguring power relations and social change. Habermasian-type dialogue in the COVID-stricken Arab world must be bi-directional: global-local, but also local-global. Internal (intra-Arab) deliberation would enhance such reflexive dialogue, in contextualised responses to international expertise recommendations. Importantly, it is not enough to ‘think globally and act locally’. In and outside the Arab region, citizens and leaders must be additionally prepared to ‘think locally and act globally’, so to speak.

COVID-19’s perils have augmented the risks of human existence, especially for the have-nots: individuals, communities and states. Arabs are scrambling for new mediums—material, immaterial, moral and political—to weather the pandemic and its manifold socio-economic-political repercussions. Reflexivity as dialogue and debate can be one step in blunting the blows wrought by COVID-19. Risk might engender an opening for civic, political, and economic players to ponder policies and activisms that can begin to reign in inequality, vulnerability, and exclusion in the Arab region.

Professor Larbi Sadiki and Associate Professor Layla Saleh.

This article is an adapted version of Sadiki, Larbi and Layla Saleh. 2020. ‘Reflexive Politics and Arab ‘Risk Society’? COVID-19 and Issues of Public Health.’ Orient: German Journal for Politics, Economics and Culture of the Middle East, Vol. 61, Issue 2, pp. 6-20.)

Image: Women’s rights march, Cairo, 2013. Credit: Ella/Flickr.