Around a dozen Australian students went to the People’s Republic of China in the late 1970s as part of an official exchange program negotiated soon after the establishment of diplomatic relations in December 1972. Their experiences, in almost every case, marked them for life and profoundly influenced their future careers.

Anne McLaren, now Professor of Chinese Studies at the University of Melbourne, was one of these students and lived in China from September 1978 to August 1979, studying first at the Beijing Second Foreign Language Institute and then at Shanghai’s Fudan University.

As the Cultural Counsellor at the Australian Embassy in Beijing in 1978, I welcomed Anne and other students on their arrival and tried to help them settle into campus life. While the embassy was not an ivory tower, life for the staff there was relatively protected compared with the privations of campus dormitories and classrooms during this tumultuous time.

This book is a diary of first-hand source material, meticulously collated and translated. It will be most valuable material for future researchers who wish to study China’s transition from the late years of the Cultural Revolution to the economic reforms of the 1980s. It is also a rollicking good read.

The 11 months from September 1978 to August 1979 saw a tectonic shift in Chinese politics and the beginning of change in the economy and society.

Mao Zedong had been succeeded by Hua Guofeng in 1976, supposedly with the blessing of the Great Leader, as evidenced by ubiquitous posters of the two and the caption “With you in charge, my heart is at ease.”

Deng Xiaoping, having been imprisoned during the Cultural Revolution, was making a comeback and by the end of 1978 had gained ascendancy.

The early months of 1979 saw the green shoots of liberalisation before Deng and his lieutenants, including Zhao Ziyang and Wan Li, established step-by-step reforms in various sectors of the economy. A contemporary popular saying referred to the reforms in agriculture successfully implemented in the provinces of Sichuan and Anhui was “If you want grain, look to Zhao Ziyang, if you want rice, look to Wan Li” (“Yao chi liang wen Zhao Ziyang, yao chi mi wen Wan Li 要吃粮见赵紫阳,要吃米问万里”).

Formal diplomatic relations with the United States were resumed on January 1, 1979. Universities revised their heavily political textbooks and experimentally adopted overseas teaching materials.

Thousands of youngsters who had been ‘sent down’ to the countryside from Shanghai during the Cultural Revolution agitated to be allowed to return home. The horrors of that decade were partially revealed, although no official consensus was reached regarding Mao Zedong’s culpability for them.

McLaren’s account of the 1979 protest movement in Shanghai is particularly interesting. Even now, it is not clear to what extent this was a spontaneous popular movement and to what extent it was encouraged or manipulated by factions in the Party and government. The movement was characterised by assemblies of large crowds in public places such as the square formerly used for National Day marches (now a park) and along walls displaying protest posters.

One prominent figure in this movement was Teng Husheng. At that time, he was as influential as Wei Jingsheng. Now largely forgotten by history, I hope that McLaren’s extensive coverage of his political platform, including his eventual arrest and disappearance/probable imprisonment, will restore him to his rightful place in the history of the struggle of Chinese people for their democratic rights.

The seven chapters of this book follow McLaren’s story in chronological order, and there is one appendix, which is a reprint of her account of her revisit to Shanghai in 1986. Much of the material appears to be reproduced from diaries and letters without editing because there is a certain amount of repetition. I hope that the original materials will be properly archived and made available to scholars because this would greatly enhance their value for research purposes in the future.

Jocelyn Chey, AM, Visiting Professor, University of Sydney; Cultural Counsellor, Australian Embassy, Beijing, 1975-78, Consul-General in Hong Kong, 1992-95.

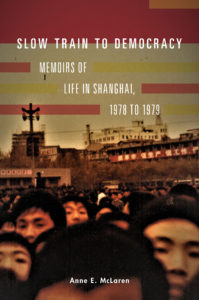

Banner image: The Shanghai Democracy Wall in the People’s Square November 1978. Book cover image: Poster movement in Shanghai People’s Square, November 1978. Credit for both images: Anne McLaren.