Over the last 50 years China has experienced tectonic shifts in its place in the world.

Professorial Fellow of Chinese studies at the Asia Institute, Anne McLaren, was one of very few Westerners to study in China in the 1970s.

Over her distinguished career she has witnessed an impoverished nation with a significant democracy movement transform into a global power displaying increasing political repression. She spoke with Melbourne Asia Review’s Managing Editor, Cathy Harper.

You were a PhD student in Beijing and Shanghai in 1978 and 1979 at a time when only a handful for foreign students were there, and months before American students were allowed to study in China. Can you paint a picture of what China was like before diplomatic relations were established and the changes through the 1970s?

Australia established diplomatic relations with China as one of the first acts of the new government led by former Prime Minister Gough Whitlam in December 1972. From around 1975 it became possible for a very small number of Australian students to go to China to attend Chinese universities for one or two years. I was fortunate enough to be one of those able to go in 1978. The United States established diplomatic relations on 1 January 1979, although they had an office in Beijing a few years before that time.

In 1978, China was in a period of transition. Chairman Mao Zedong, the founder of socialist China, had died only two years earlier. His chosen heir, an obscure man called Hua Guofeng, was the new Party Chairman and he was vowing to follow whatever Mao had instructed during his life—so it didn’t look like much would change.

Under Mao, China underwent 30 years of more or less continuous campaigns. The most ruinous were the Great Leap of the late 1950s, followed by three years of famine and the so-called Cultural Revolution that reached a heyday of violence and mayhem from 1965 to 1968, followed by military repression thereafter.

In 1978, the Chinese population that I saw was impoverished, malnourished and disease-ridden. Food was very tightly rationed (especially grain, rice, oil, meat and eggs). Vegetable and fruit supply tended to be limited in range and often in volume. Bolts of cloth (most people wore cotton cloth) was rationed, as were bicycles, sewing machines and much more. Many people did not have modern facilities of hot and cold water, proper sewerage or clean water to drink; Shanghai did not have heating in winter. Due to the crush of people in densely populated dwellings and the lack of basic sanitation, there were numerous health problems including tuberculosis and hepatitis

We foreign students shared in some of the hardships. However, we were not subject to food rationing and did not go hungry, but many things were scarce and hard to buy (such as fruit). We were given vouchers to buy a bicycle. At Fudan University in Shanghai we did not have hot water in our building, only cold water. The only drinking water came from a thermos that we filled ourselves. However, we were able to have a shower in the communal university shower block during a two-hour period most days of the week. There was very limited heating and we were often cold.

The other aspect was psychological—many of the people we met had very concrete grievances because of 30 years of stagnant economic growth and political campaigns that had disadvantaged their family. Young people in particular felt a sore lack of opportunity and many had a sense of hopelessness.

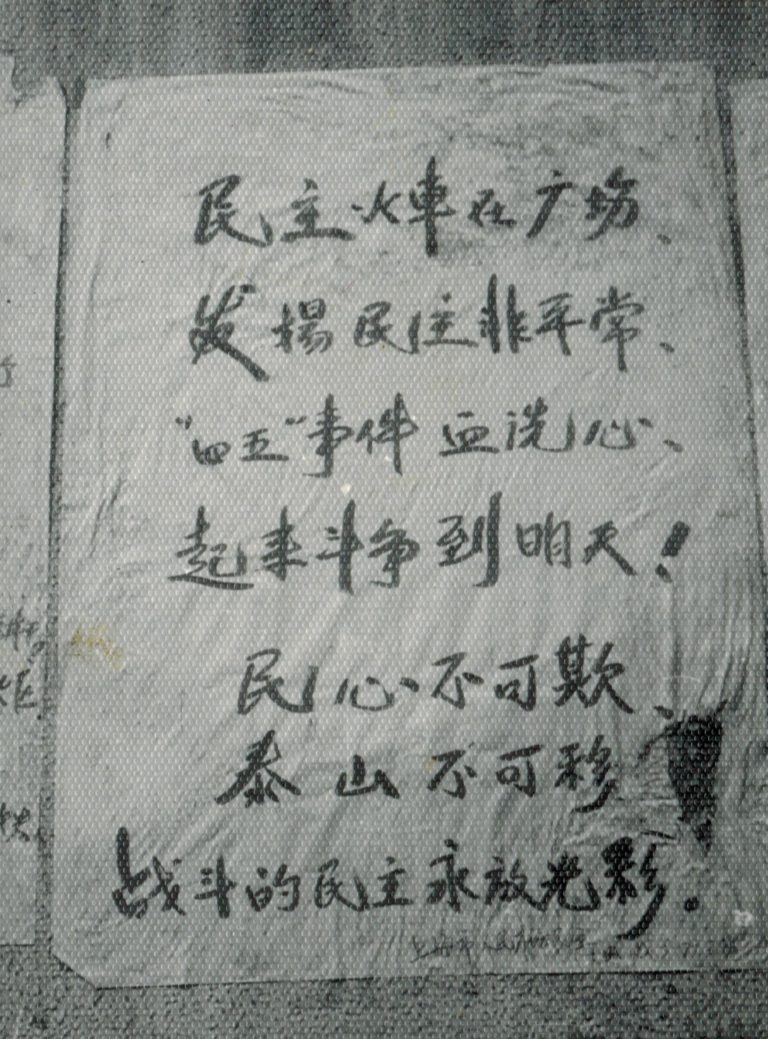

Your recently-published memoir ‘Slow Train to Democracy’ is an account of a time in China when there was a democracy movement in Shanghai, when posters were published in prominent public places criticising the failed policies of the Chinese government, and Chinese students spoke much more freely about politics. What’s your analysis of the impact and significance of this period in China?

The democracy movement in Shanghai and in Beijing in late 1978 was particularly interesting because it arose directly from grievances with the Chinese government and was not influenced by foreigners, it was an indigenous movement. If we compare the poster protest movement of 1978 with the Tiananmen protests of 1989, the really big difference is that the latter drew from Western democratic symbols (the Statue of Liberty for example) and some of the student protestors drew from Western ideas. They were in fact inspired by Western notions of democracy (often heavily romanticised), but this was not the case in 1978. At that time China had been sealed off from the outside world. The educated population did not learn English, they learnt Russian. Western literature, books of ideas, even Western music like Beethoven, were banned as bourgeois and not acceptable for much of this period.

The other interesting thing is that some of the Shanghai protestors strongly condemned Chairman Mao and implicitly the leadership circle of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Mao was blamed as the instigator of the Cultural Revolution that had ruined the lives of so many in the younger generation. They were deprived of an education as schools and universities largely shut down in the late 1960s. In the aftermath of the peak violent period, hundreds of thousands of young people were sent away from the cities to work in communes and state farms, often in desperately poor circumstances. Now they felt they had been robbed of a future.

What was really interesting about the protest movement of the late 1970s is that they called for a rejection of the agenda of the first 30 years of socialism in China. They were the first generation in China to directly condemn Chairman Mao, which they did in numerous wall posters and harangues in public sites. This was really unprecedented. Mao had died only two years before and you would have to say this was a really courageous thing to do. If you did this in China today it would not be tolerated. The other interesting thing was that this group sought to put into practice the rights theoretically guaranteed to citizens, such as freedom of speech, freedom of the press, the right to hold gatherings, to establish societies, to hold rallies and to go on strike.

All were united in calling for democracy, although it was unclear exactly what they meant by this. The most radical group I came across, “The People’s Democracy Forum”, told me they were interested in parliamentary democracy and hoped to establish their own party. Their leader was later arrested for “attempting to overthrow the communist party”. However, I think that for most of the protesters, democracy meant the right to hold the government to account, to voice their grievances, and have their concrete problems addressed. The more thoughtful of the protesters wanted the government to reflect on the systemic problems that had led to the disastrous campaigns of the Maoist era, particularly the cult of the Great Leader. The protest movement continued for several months but was ultimately repressed by the authorities and leading figures were arrested.

The protest movement of 1978 in Beijing and Shanghai has been covered up in China and the younger generation is not informed about these movements. Nor are they told much, if anything, about what happened in 1989, especially the brutal repression of the Beijing population by the Peoples Liberation Army in June 1989. But it is important to call these events to mind because they still frame the judgement of the CCP leadership in the present day.

In retrospect, we can say that the protest movement of the late 1970s laid the foundation for a series of political clashes between the people and the communist party. There have been numerous democracy movements in China since 1978. In Shanghai there was another one in 1986 (which I also witnessed) then the convulsive events of 1989 at Tiananmen Square. In 2008 there was the constitutional movement led by Liu Xiaobo and artist, Ai Weiwei. Liu was later awarded the Nobel Peace Prize but died in a Chinese jail in July 2017. Even this year there have been voices calling for political reform and voicing disgust with the new Chinese “emperor”. Tsinghua University professor Xu Zhangrun has written a series of essays that have been published in Chinese and in English. He has now lost his university post and even his university pension. The regime is vindictive to those who voice complaint. The 1970s movement is still relevant because the key demands of the people, that is, for political reform, protection from arbitrary justice, and greater democracy, have still not been met.

The tolerance of critical views, even if brief, during your time in China contrasts starkly with the heavy crackdown on any political dissent currently being shown by the Chinese Communist Party. What are some of the factors that have contributed to this?

It is certainly interesting that today it is not possible to come forward in a public forum and condemn Mao Zedong or the communist party leadership in the same fashion as the 1978 protestors in Beijing and Shanghai. And, needless, to say, you can’t come forward and criticize the current Chinese leadership at all. This reminds us again that China has engaged in economic opening up and reform, but not in political reform. The young people of the late 1970s wanted both economic and political reform. Their hopes were not realised.

Concerning the factors contributing to the current repression in China, the CCP has never learned to trust its own people. This is why it has set up such a repressive regime under the leadership of Xi Jinping. This is strange in some ways. Many people are much better off economically and there is little organised resistance to CCP leadership. In fact, surveys point to a general acceptance of the rule of the CCP largely by default, as there appears to be no alternative. China is a big and complex country and many people still have ‘the emperor complex’, that is, you need a big and powerful leader to weld a country like this together or it will fall apart.

The CCP fears it may go the way of the former USSR if there is too much opening up and free-wheeling thinking. I think this is a big mistake. If you repress people too much there will be a push back sooner or later. This pushback may come when it is time for Xi Jinping to step down (or he may find himself pushed out of power by his numerous political enemies).

I think there are various reasons for the current situation of repression. One is that the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 led Xi to think that the West is weak. And after the GFC, even though we’ve recovered to a certain extent the US doesn’t really look like it can keep its role as the world’s leading economy for that much longer. So Xi cast aside the earlier policy of Deng Xiaoping that had been followed since 1978, which is basically ‘bide your time, lie low’ and he’s now promoting China’s so-called “peaceful rise”. From that we get the Belt and Road initiative, we get more diplomatic assertiveness, we get the takeover of the islands in the South China Sea, and so on.

China will have grave problems in the future with climate change and food security, and its aging population. So from Xi’s point of view, now is the time to move.

However, the China of 2020 is not at all the impoverished nation of 1978. It’s not just that China is wealthier, the people are more highly educated and sophisticated. One could quote here the words of Li Fan, Director of the World and China Institute, and an early advocate of direct elections at village level in China. He wrote in July 8 this year: “The ideas of rule of law, civil society, freedom and democracy have been deeply planted in the hearts of the Chinese people”. Writing from outside China, scholar Ci Jiwei argues that the current past of Xi Jinping will ultimately lead to the downfall of the CCP and a new more democratic China. Both of them argue that civil society and self-organised groups have already taken hold in China and are pushing back against authoritarianism.

What’s your assessment of the current relationship between the West and China, particularly Australia and the United States? Beyond recent developments, what’s your more historical perspective on the last 50 years or so of diplomatic relations.

When I see the current state of Sino-Australia relations I feel sadness and grave concern. Relations are at a nadir. It’s not quite as bad in 1971, but we unfortunately look like getting back towards that time when here was a Cold War situation and China was isolated. It was still a threat because it had nuclear weapons and Australia saw China as a threat.

But what we have achieved in 48 years is very substantial people-to-people relationships. Students and businesspeople and lots of tourism. Throughout my career I have been most engaged in people-to-people relations with China such as teaching Australian students Chinese, sending them to China, visiting China myself to do research, meeting fellow scholars in China with similar interests and welcoming Chinese scholars to Australia. I do really hope our universities will not feel constrained in continuing these very important people-to-people relations. The Asia Institute and Asialink promote people-to-people links in culture and business and it’s vital that this sort of engagement continues. People-to-people contact needs to be quarantined from the more fractious issues of diplomacy and security. It should be possible to do this while remaining sensitive to the areas of concern on both sides, both in China and in Australia.

Main image: Street scene in the old city, Shanghai (1978-1979). Credit: Anne McLaren.

Secondary images: Boy hauling concrete in Tai’an Shandong (1978-1979); poem poster: The Democracy Train is in the Square, Shanghai (1978-1979). Credit: Anne McLaren.