In this Melbourne Asia Review edition on ‘Environmental Creativity in Southeast Asia: Nature beyond the Nation-State’, we focus on individuals and groups who use visual art and other creative media to raise critical awareness about, and provide possible solutions to, some of the key anthropogenic disasters with which the region has been grappling, including droughts, floods, forest fires, and water, air and soil pollution. We are interested in creative actors who go beyond nationalist euphoria about economic progress by critically addressing the intersections between politics, business and the destruction of nature, including historical continuities between colonial and post-colonial trade and agricultural policies and practices.

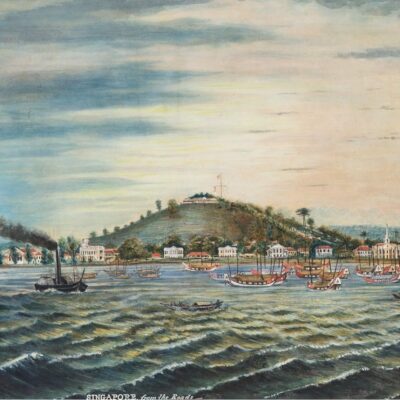

Since the arrival of European colonialism, the biodiversity of large parts of Southeast Asia has been drastically reduced due to the impact of natural resource extraction, monoculture farming, intensified travel and trade, infrastructure development, urbanisation, industrialisation, consumerism, and war, among others. Post-colonial governments in the region have used nationalist discourses around economic development to continue, intensify and justify environmentally destructive policies and practices. At the same time, there has been growing concern among community groups, youth, activists, artists, academics, policy makers and others about the environmental, social, cultural and financial impact of national and regional development projects.

The ongoing, complex and often heated debates around climate change in Southeast Asia and worldwide since the 1980s demonstrate that the core problems of our geological age are not only environmental or ecological as such, but also representational. The representational issues are manifold, ranging from the complexity of the problems, and the lack of human mutuality with the other-type ontologies, temporalities and scales of geological phenomena, to the socio-political power structures limiting access to and participation in climate debate and action.

This edition focuses on environmental creativity from Southeast Asia as a critical, imaginative and affective form of communication that has the potential to reflect on and overcome some of these representational challenges. We analyse a variety of creative media and genres, including visual art, film, literature, photography, design, and curatorial practices to enrich the field of the environmental humanities with regional perspectives beyond the modern state and colonial discourses.

The challenges of representing the Anthropocene

Limitations to creating environmental and ecological awareness and action are due, among other things, to more-than-human objects, such as nature and climate change, resisting representation. Timothy Morton coined the concept ‘hyperobjects’ to refer to phenomena that seem to be beyond human grasp, such as our planet, the biosphere, the sum of natural resources, Black Holes, and the solar system. He explains that these hyperobjects share forms of viscosity, (non)locality, temporality, and interobjectivity that are beyond human scale or understanding.

Similarly, Dipesh Chakrabarty argues that the abstract, astronomical idea of ‘the planet’ as mass of matter deposited somewhere in the universe has been ‘an impossible matter of ethico-spiritual concern’, or ‘merely a background to human dwelling’. Despite ongoing encounters with the planet in the form of natural disasters such as earthquakes, volcano eruptions and tsunamis, and despite the study of ‘deep earth’ and ‘deep time’ with the emergence of the discipline of geology in the eighteenth century, the planet has never settled in humanist thought. According to Chakrabarty, this lack of mutuality is now truly felt in ‘the crisis of the Anthropocene’.

Another key factor is the human politics of representation. Historical and contemporary power structures have determined the selection of groups and individuals participating in and controlling the climate discourse, the nature of the discourse, and the production, distribution and reception circumstances of such discourse. The environmental stories and ecological wisdom of marginalised groups, including Indigenous communities and women, as well as the agency of nature itself, have been structurally excluded or only received restricted circulation and appreciation.

Environmental thinkers and activists have pointed to not only the perseverance of climate contrarianism, but also the claimed authority of ‘anthropocenologists’ who postulate each individual or community as equally responsible for the Anthropocene, thus ignoring histories of colonial domination and inequality among people. Instead of adopting the common notion of the Anthropocene as the geological age in which human activity has become the dominant influence on the natural environment and ecosystems, critical environmental thinkers and activists seek to demonstrate how climate change and histories of political, social, and cultural injustice are interrelated. They have proposed alternative concepts to include more voices, identify the specific social, political, and historical factors behind the environmental problems of our age, and differentiate between the various actors responsible for, affected by, or seeking solutions for anthropogenic disaster. Some of these concepts, such as the Agnotocene, Capitalocene, Eurocene, Homogenocene, Phagocene, Phronocene, Plantationocene, Plasticene, Technocene, Thanatocene and Thermocene, point to the main culprits of environmental disaster, while other concepts, such as the Gynecene and Chthulucene, promote alternative, more environmental-friendly forms of social, political or economic organisation and connectivity.

A complicating factor in facilitating more in-depth, inclusive and diverse debate is the contradiction between the ‘slow violence’ of phenomena such as climate change, and the narrow instantaneousness of the, increasingly algorithm-driven, media industry and consumption practices. Rob Nixon, who coined the term, explains that the representational challenges include the relative invisibility, slow unfolding, past origins, and delayed and changed effects of the environmental phenomena. These challenges are exacerbated by the prioritisation of fast and spectacular representation styles by the commercial media; the increasingly limited concentration span of media consumers; the immediate result and popularity-focused policies of short-sitting governments; the reliance of digital and other communication industries on natural resources for innovation, production, and distribution; and the increasingly faster turnover of consumer gadgets such as mobile phones and computers producing highly toxic e-waste, often with lower income and climate-vulnerable countries as its dumping ground.

While the environmental stories are subject to ideological influence or pressure from the direct or indirect political participation of media oligarchs around the world, the contemporary ‘post-truth’ climate associated with the rise of Artificial Intelligence and digital platforms such as X and Facebook goes beyond ideological propaganda, manipulation, exclusion, or censorship as such. Rather, it is linked to the problem that the data related to the creation and sharing of online content has become a commodity in its own right. Within this economic system, the nature of the content is less or not relevant, as both truths and non-truths about the environment and other topical issues boost the lucrative generation of data. Post-truth is no longer a matter of true or false, or morality and responsibility, but a cornerstone of the political economy of commercial communication platforms and a key challenge to everyone with sincere environmental concerns or action plans.

The role of environmental art and popular culture

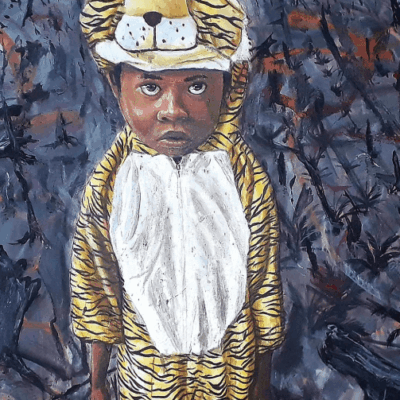

The various representational challenges imply that deeper understanding of the planetary crises of our time cannot rely on scientific analyses and proposed solutions only, but also requires the insights from the Humanities and Social Sciences and their objects of study, including the arts. In this edition of Melbourne Asia Review, we seek to analyse how artist-activists go beyond the discourses or propaganda of states, businesses or prominent ideological groups, by collaborating with or providing a voice to people underrepresented in politics and the media, particularly those with everyday experiences of and deep wisdom about nature and environmental disaster. Some of their creative expressions acknowledge and mediate the agency of nature and planetarity, Indigenous laws and storytelling, and ecofeminist practices and thoughts. We also examine how artist-activists establish online and in-person networks and hubs, as means for sharing experiences, knowledge and ideas, and strengthening the message and reach of their creative work.

Our authors employ interpretative frameworks that resonate with the geographical, natural, socio-political and (art) historical dimensions of Southeast Asia, including ‘a regional eye’ (Roger Nelson), ‘sea change’ (Gillian Daniel), ‘viewpoints on design’ (Juhri Selamet and Alexandra Crosby) and ‘museum climates’ (Nicole Tse). These approaches consider regional continuities and ruptures with colonial regimes of controlling and representing the natural environment. They are not limited to the critical and imaginative perspectives presented in contemporary art and popular culture, but also take into account the materiality of the creative objects themselves. The latter includes the cultural politics and social and environmental conditions of the design, collection and preservation of art works (Tse, Crosby and Selamet).

Other authors (Laurence Marvin Castillo, Gaik Cheng Khoo, John Charles Ryan) analyse the interventions provided by more direct forms of creative activism, including Indigenous artists using contemporary media in their struggles for environmental protection and cultural and political rights. For these and other local artists, traditional genres of storytelling, including epics (Tom Davies), do not contradict, but enrich, contemporary art and literature as sources of creative inspiration and ecological wisdom. A special interview with researcher-artist Elia Nurvista focuses on how creative engagements with food and food production can address environmentally and socially harmful interventions in Indonesian landscapes and agricultural processes. Building on a corpus of pioneering studies, our overall aim is to explore what insights the study of Southeast Asian creative ideas and practices and their relevant socio-political and cultural contexts can contribute to the emerging field of the environmental humanities.

Image: Aerial view of waves crashing on a sandy shore. Credit: RDNE Stock project/Pexels.