It seems hard to deny that we are in a state of deepening climate crisis, especially in the face of escalating and increasingly regular episodes of environmental catastrophe. And yet, as many organisations, scholars and activists have deplored, there remains a disproportionate response from governments and international bodies. In Southeast Asia, recent public surveys concerningly demonstrate that there are falling levels of perceived climate urgency. A theme that emerges through the work of some of our most critical climate thinkers is that this inaction is exacerbated by challenges of vision and imagination. It is difficult to envision the sea change to our ways of thinking and being that is required to address our climate challenges at scale, and the consequences if we do not.

But, as art historian and cultural critic TJ Demos has argued, art can play a role where imaginative tools are needed to address the climate emergency. Recent research has demonstrated that art can critically contribute to climate communications by offering affective alternatives to raw data that can elicit skepticism and worsen political division. The cultural institutions that hold art objects play a vital role in shaping collective ideas, by presenting stories of self, society and world to the public. In this vein, I argue that an eco-critical re-examination of colonial-era maritime pictures of the Straits of Malacca and Singapore within public institutions can help prompt the attitude shifts necessary for public and political action. These paintings and prints are frequently displayed to frame state narratives. When re-framed, they can reflect the impact of human activity on coastal environments and communities and remind us that these changes were instigated by colonisation. They can also reshape our understanding of the natural world.

The significance of maritime paintings

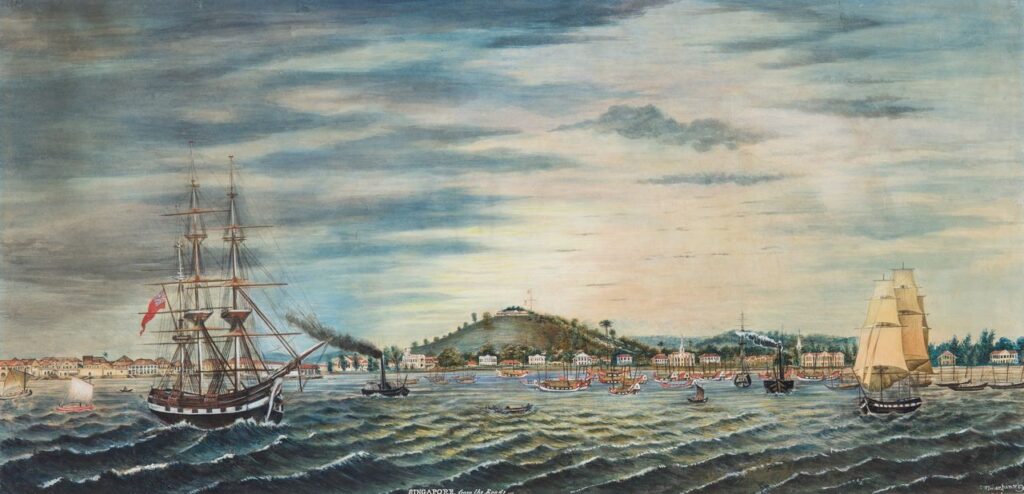

Maritime pictures became hugely popular in the 18th and 19th centuries alongside the rise of the British seafaring empire. As pivotal events of national and imperial importance occurred overseas, there was greater demand for visual representation of them. The genre’s popularity spread to the Straits from the late 18th century, when Britain sought a stronger presence in Southeast Asia because of a series of decisive historical circumstances. These included the American Revolution of 1765 to 1783, which caused an unraveling of the British Atlantic Empire; the victory of the East India Company (EIC) in the Battle of Plassey in 1757, which allowed the rise of British India; the EIC’s export of opium between India and China, in response to large trade imbalances between Britain and China; and the Dutch spice monopoly in Southeast Asia, which enabled their growing dominance.

A British settlement was established in Penang in 1786, with a second in Singapore in 1819, that would eventually become the administrative centre of British Southeast Asia later in the 19th century. In response to these changing historical conditions and demand back home from admiralty, academy and audience, travelling British artists widely represented events and places overseas. Works made in Southeast Asia were taken back to Britain, where they made their way into major public institutions such as the British Library. Some also remained regionally, where they became part of the founding collections of state and national institutions after independence, such as the Penang Museum and the National Museum of Singapore.

From the late 20th century to the present, maritime pictures from these international institutions have been commonly activated in articulations of state and national identity in Singapore and Malaysia. This current framing is due to the way these works illustrate the role of the port in national development. Penang and Singapore were chosen as sites for settlement because of their location in the Straits, which is a critical passage that connects lucrative sea routes between the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. They were designated free ports (tax free zones to stimulate business activity) upon settlement, in a move counter to the existing trade practices of Indigenous peoples and other Europeans in the region. As a result, they developed rapidly, Singapore especially. Within a few decades, Singapore became one of Southeast Asia’s major ports.

After independence, Singapore and Malaysia continued to focus on the growth of their Straits ports. Today, the commercial performance of these free ports are a consistent source of national pride, as observed through media outlets and political rhetoric. When analysed as a considerable body of pictorial records, maritime pictures of the Straits reflect the transformation of the region’s coastal environments and its role in developing the productive and profitable settlements that laid the foundation for contemporary port cities. These works have thus been important touchpoints in framing national identity.

But while the successful control and commercialisation of the waters have undeniably benefited nations after centuries of colonisation and then decades of post-colonial struggle, ever-intensifying maritime industrial activities have taken a serious toll on ecosystems and communities in the Straits, for example through catastrophic oil spills, natural habitat degradation, impact on coastal communities, and loss of Indigenous culture. It is therefore necessary to take a step back from our well-worn narratives and fundamentally rethink humans’ relationship to the natural world.

The impact of colonisation on coastal ecosystems

As has been established, our relationship with the environment today is inextricably linked with European colonial systems of knowledge. Colonisation was a regime that was not only concerned with restructuring societies but also reordering nature. Colonial ideas of the difference between the human and nonhuman worlds cast the latter as inert, commodifiable and separate. This laid the foundation for the current dominant worldview that sees the nonhuman world primarily as a resource for the benefit of humanity. As a prevalent form of cultural production that was widely made and consumed across Britain’s far-ranging empire, maritime paintings played a role in socialising colonial ideas of nature.

Image 1: Ensign Caldwell. H.M. Brig, Viper – 16 Guns Sailing Between the Little Island of Pulo Reyma and Pulo Penang. 1778. Watercolour. 27.5 x 49.1 cm. Penang Museum.

One of the earliest British maritime pictures of the Straits is a painting from 1778, H.M. Brig Viper – 16 Guns Sailing Between the Little Island of Pulo Reyma and Pulo Penang by an artist who signs off as Ensign Caldwell. The watercolour was the first artwork featured in a landmark publication by the Penang Museum. Pre-dating settlement by eight years, it depicts a British warship sailing on the Strait of Malacca in between Penang Island on the right and Pulau Rimau on the left. Along the front banks of Penang Island, tall palm trees rise above the thicket of the jungle canopy. These details indicate the scene’s tropical setting. Behind, the rest of the vegetation is rendered in shadow, hinting at the presence of fecund lands still to be discovered, known and therefore taken. The composition of the work draws our attention to a passage between the islands. Like a stage, the sea is calm. Like stage curtains, the islands part gracefully to reveal Caldwell’s protagonist: the Viper. The ship is shown to be fortuitously catching a tail wind as it makes its way across the waters in the direction of land. Through these pictorial choices in line with established conventions of maritime painting, Caldwell foregrounds human mastery of a passive environment full of natural abundance. As the British Empire expanded in the Straits, more works like this were created.

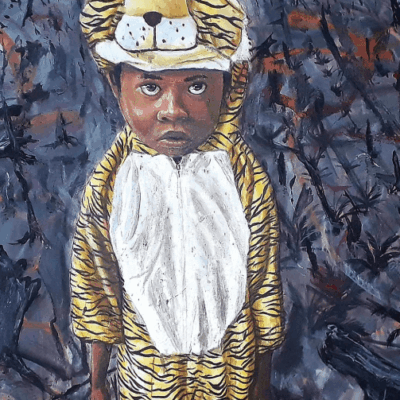

By the mid-19th century, maritime activities exponentially intensified as a result of imperial expansion and developments in technology. Works from this time show a different scene to that of Caldwell’s, as artists highlighted the flourishing nature of Straits ports, changing coastal environments and new maritime technologies. Again, their depictions followed artistic conventions and perpetuated a distinctive visual vocabulary. This mid-19th century colonial imaginary of the bustling, technologically advanced, and cosmopolitan port still holds powerful currency in articulations of national identity.

Image 2: Robert Wilson Wiber. Panoramic View of Singapore from the Harbour. 1849. Watercolour and gouache on paper. 33 x 67 cm. Collection of National Gallery Singapore. Image courtesy of National Heritage Board, Singapore.

An example of this kind of work is Robert Wilson Wiber’s Panoramic View of Singapore from the Harbour from 1849, which was included in a permanent display at the National Gallery Singapore. Beyond the large British merchant vessel at anchor on the left and the European sailing ship on the move on the right are numerous Chinese junks and Indigenous perahu. Two black steam ships leave distinctive trails of smoke, reflecting the pivotal changes in maritime infrastructure that revolutionised shipping. The shoreline, which would have once resembled the thicket of tropical rainforest in Caldwell’s watercolour, is now lined with buildings, including European-style neoclassical landmarks. Rising above the waters over the shoreline is Government Hill, which was cleared to make way for the residence of the colonial governor and the flagstaff that are visible at the peak. From the way these occupy a central and elevated position, the composition implies colonial dominion over the port. Wiber’s work is one of many exploring the thriving nature of the port that have been featured in state institutions across Singapore and Malaysia.

Works like Caldwell’s and Wiber’s have long been used in the region to frame the nation, but if we examine them through the lens of the current climate emergency a different story emerges.

Maritime pictures related to the bustling port gesture to the fact that 19th century Southeast Asia experienced some of the most explosive growth of sea traffic in history. The adverse effects of shipping traffic on ecosystems, such animal behaviour modification and chemical pollution, is well known. In Caldwell’s painting, the 16-gunned British warship and the small, unarmed Indigenous perahu are reminders that colonisation was a form of war-making between imperial players, as well as between these European powers and their colonised subjects. Although it is difficult to tell if Wiber’s steamships are armed, 10 years before the work was made, Britain deployed the Nemesis, the world’s first steam-powered warship, which went on to decimate Qing forces in the First Opium War. This irrevocably changed war-making, by making fossil fuels central to the pursuit. Today, militarisation consumes so much fossil fuels and produces such harmful byproducts that it has been called ‘the single most ecologically destructive human endeavour’.

To enable the expansion of the settlements, huge swathes of rainforest were cleared. In Singapore, this resulted in near total deforestation. Government Hill, which is centrally featured in Wiber’s work, was once called Bukit Larangan (‘Forbidden Hill’) and was a site of spiritual and historical significance to local groups. Its Indigenous symbolism was one reason it was chosen as the site for the colonial governor’s residence. The contrast between Caldwell’s and Wiber’s works illustrate that, with colonisation, the waters became busy, fossil fuels formed a new world order, first-growth rainforests were cleared, and Indigenous sites disappeared. As previously discussed, the consequences of this on coastal ecosystems and communities have worsened with the intensifying commercialisation of the Straits after decolonisation. Maritime pictures visualise the impact of centuries of human activity on coastal environments that was supercharged with colonisation.

Nature’s agency

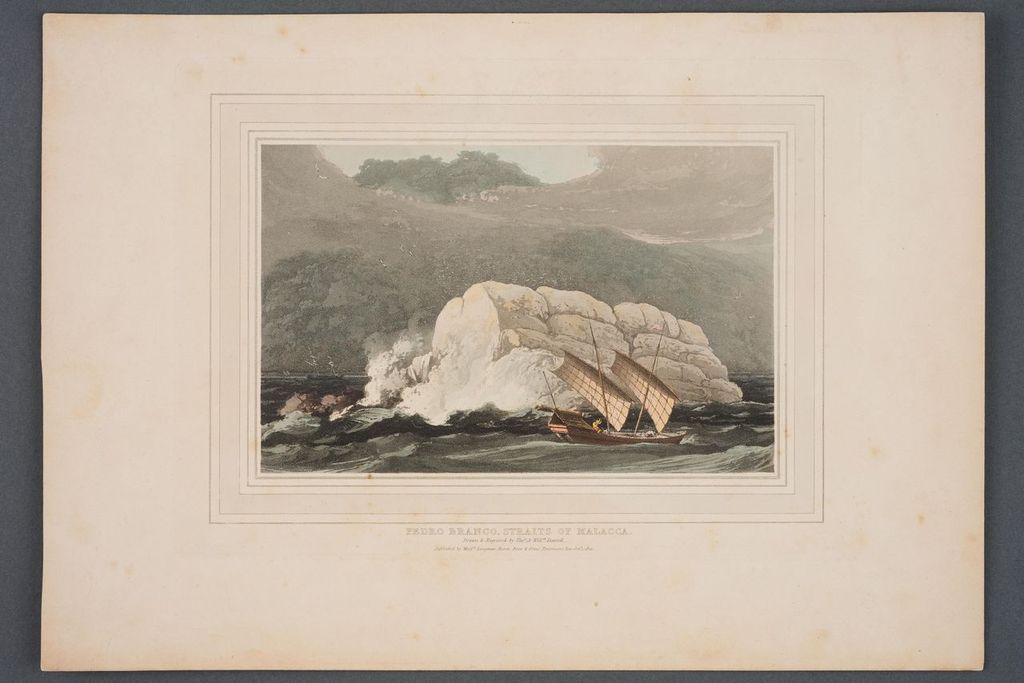

There exist less featured works that point to how the Straits have always shaped and limited human efforts to control them. Throughout the colonial period, the Straits had a reputation for being a particularly perilous stretch. Equatorial monsoon winds bring regular vigorous thunderstorms known as Sumatra squalls. Ships passing through the narrow waterway must navigate hidden sharp rocks and reefs. Europeans thus frequently relied on the guidance and knowledge of Orang Laut (Indigenous ‘people of the sea’) for safe passage.

Image 3: Thomas and William Daniell. Pedro Branco, Straits of Malacca. Published in 1810. Aquatint. 18 x 24.5cm. Collection of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board. Gift of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee.

The professional artists Thomas and William Daniell travelled through the Straits in the latter half of their journey between 1785 and 1794 from Britain to China and India, which was published as an account in 1810 with 50 prints. One of the memorable experiences they documented was sailing the waters around Pedra Branca, at the Eastern exit of the Strait of Singapore. In the work, the islet’s rock face is characteristically white from the guano that gave it its names: ‘Batu Puteh’ in Malay and ‘Pedra Branca’ in Portuguese, both meaning ‘White Rocks’. Wrote the Daniells, ‘So violent is the surge at this point, that the boldest navigator might rejoice to leave it behind him.’ The work uses scale to illustrate the immense power of nature over human beings. The breakers that crash upon Pedra Branca rise high above the sails of an Indigenous perahu sailboat and a European ship that veer sharply to stay clear of the islet, dwarfing the two sailors struggling with the perahu’s lines. As the British empire expanded in the early 19th century and more ships passed through the Straits, the stretch of water around Pedra Branca caused numerous shipwrecks and other maritime disasters.

To alleviate the situation, the colonial government in Singapore constructed the Horsburgh Lighthouse in 1851. An oil painting by John Turnbull Thomson, the Government Surveyor who led the project, uses scale and composition to emphasise the lighthouse’s height and sturdy nature as it is surrounded by swirling seas. The first of its kind in Southeast Asia, the Horsburgh Lighthouse improved safety and formed part of a heated race between the British and the Dutch to light the seas for better imperial oversight. However, in the Turnbull work, a ship on the left swerves precariously, recalling the vessels in the Daniells’ print. Even with impressive new technology, the natural conditions of the Straits remained difficult to navigate and survive. Infrastructure has improved since the mid-19th century but this stretch of water is still the cause of maritime disasters. These works are reminders that the Straits cannot be controlled.

Figure 4: John Turnbull Thomson. Horsburgh Lighthouse. 1851. Oil on canvas. 46 x 69 cm. Collection of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Conclusion

In response to the systemic sea change needed to address the climate crisis, and in line with current research about the potential of art in climate discourse, maritime pictures of the Straits can be useful tools to prompt attitude shifts. The works discussed in this article are held in cultural institutions with consequential reach. Wiber’s painting was on long-term display at National Gallery Singapore, where over 3 million people experienced exhibitions, programs and digital content in 2024. The Daniells’ print and Thomson’s painting are held by National Museum Singapore, which reported visitorship of over 1 million and digital viewership of over 105 million in the same year. In these contexts, rethinking which works are presented and how they are framed to also pay heed to the climate crisis has the potential to significantly impact public imagination. These works can emphasis the need to re-examine our relationship to the natural world by offering visual evidence of how coastal environments have changed and how our current relationship to them emerged from colonial ideas. By alerting us to the vitality and significance of nonhuman actors, they can also help shift dominant understandings of the natural world as inert resources. In these ways, re-examining maritime pictures can help shape the public attitudes necessary for political, economic and social change.