Pakistan is a Sunni Muslim majority country and its historical and political development relate a compelling narrative of a struggle to define a stable and inclusive sense of Islamic nationhood. Indeed, Pakistan was hailed as an ambitious and unprecedented Islamic experiment.

It was created in the name of Islam in August 1947 and emerged as the culmination of a Muslim nationalist struggle based on the two-nation theory: that Muslims and Hindus in (colonial) India comprised distinct nations and required separate, sovereign states. While the ideological underpinnings of the Pakistan movement often proved ambiguous and at times conflicting, the vanguard of its leadership promised an Islamic utopia often using powerful metaphors including the founding and archetypal Medinan state of the Prophet Muhammad to describe the future state.

Independence, however, brought forth sobering realities. Pakistan was set up not as the first Islamic state, but as a sovereign dominion with a Westminster style secular, parliamentary system of government where both the role of religion and the place of religious minorities remained uncertain and contested. Not surprisingly, the initial process of constitution-making revealed deep divisions between those who reasoned that Pakistan should be an Islamic state and others who argued for a secular Pakistan—warning that entangling religion with state affairs would denigrate religious minorities and involve undue state intervention into their lives. These fundamental differences were frustrating for Pakistan’s constitutional framers, not least since squaring classical conceptions of Islamic government with the framework of the modern nation-state proved difficult. This meant that it was easier to draw on Islam in symbolic or aspirational terms than it was to detail the minutiae of Islamic governance in concrete or specific forms. Indeed, the Objectives Resolution of 1949, a vague and opaque document, laid down the foundational principles of a future constitution and bound Islam to the identity and sovereignty of Pakistan (much to the dismay of religious minorities). But the earliest constitutional drafts said little about the role of Islam in the state except in nominal terms.

The consequence was an unclear situation. This was concerning for both minorities and religious groups pushing for an Islamic state. Despite assurances made in the Delhi Pact of 1950 (Nehru-Liaquat Agreement) and the Report of the Committee on Fundamental Rights of Citizens of Pakistan and on Matters Relating to Minorities (adopted by the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan on the 7th September 1954) that minorities would enjoy full rights and safeguards, the mixed messaging apparent in the constitutional drafts and documents suggested that the fate of religious minorities would be uncertain. The 1949 Resolution, too, promised that adequate provision would be made for minorities to freely profess and practice their religion and develop their cultures. But what those provisions were, and whether they emanated from Islam, and consequently derived from religious mandates insulated from political deliberation, was notably unclear.

The ulama (traditionalist Islamic scholars) and Islamists such as the influential Mawlana Abul Ala Mawdudi petitioned against the contradictions in constitutional drafts, noting in a joint statement entitled the Ulema’s Amendments to the Basic Principles Committee’s Report that concrete policies and detailed steps are required to turn Islamic social and political aspirations into something tangible.

The twists and turns of these developments were taking shape alongside debates over the national language of Pakistan. The differences on this issue generated heated political tension and confrontation over which language and culture was more Islamic than the other. Advocates of Urdu noted the revered founding father of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who reasoned that Urdu was the obvious choice since it was ‘a language which, more than any other provincial language, embodies the best that is in Islamic culture and Muslim tradition and is nearest to the language used in other Islamic countries’. Those who suggest otherwise, he argued, are ‘really the enemy of Pakistan’. Jinnah’s goal was to weaken ethnic, provincial identities which posed a threat to the territorial integrity of Pakistan. Islam and Urdu afforded him the opportunity to build a supra-ethnic identity, but the unfolding politics around the issue of a national language signalled a troubling message that to be more Islamic is to be more Pakistani and that those who were not as Islamic could not be trusted. Bengalis, who formed the majority, opposed the move to constitutionalise Urdu as the sole national language. But this resistance was met with state suppression, suspicion of Bengali culture as a lesser culture of questionable Islamic credentials and a discourse around the need to Islamise Bangla which included a proposal to change the Bengali script to an Arabic script.

These events explicate a troubling pattern of distrust and repression of those rendered either un-Islamic or not Islamic enough; and religious minorities receive the brunt of this suspicion. As Pakistan continued in its struggle to establish a constitutional compact, the political deadlock proved frustrating and raised the stakes of the deliberation. Religious minorities were framed as a potential fifth column and a stumbling block to the realisation of an Islamic Pakistan. Indeed, the debate over separate electorates for religious minorities centred on whether these communities wielded political influence disproportionate to their size and would then conspire to obstruct the Islamisation of the state. Notable ulema-led Islamist groups like the Jamiat Ulema-e Islam propounded this fear urging that separate electorates would contain the political power of minorities. The tensions over the place of minorities and the Islamic commitment of Pakistan’s political leadership climaxed during the anti-Ahmadi riots in 1953 as Islamic groups demanded the removal of politicians and civil servants of the Ahmadi sect from government. The findings of a court investigation into the tumult (famously known as the Munir Report) revealed that no two Islamic scholars agreed even on the foundational questions of who was in fact a Muslim. The investigating judges noted: ‘if we adopt the definition given by any one of the ulama, we remain Muslims according to the view of that alim but kafirs according to the definition of everyone else.’ If an Islamic state was the ultimate goal of Islamist activists, the findings of the court spotlighted difference far more often than consensus in matters of religion, theology, and state.

A fundamental conundrum for the judges was this: ‘None of the ulama can tolerate a State which is based on nationalism and all that it implies; with them millat and all that it connotes can alone be the determining factor in State activity.’ This tension was difficult to square, and the approach of the Constituent Assembly was to ignore suggestions or propositions based on the classical concept of a caliphate.

The Constitutions of 1956 and 1962 emerged under authoritarian rule with little care for, or consideration of, Islamist ideologies and politics. The 1956 Constitution established Pakistan as the ‘Islamic Republic of Pakistan’ and prescribed Islamic provisions which extolled Islamic social and moral virtues, relegated Islamic principles of governance to directives of state policy, featured non-justiciable repugnancy clauses which mandated that all laws should conform to Islamic injunctions and laid down instructions for the creation of advisory Islamic institutions. In other words, these provisions were a far cry from the Islamic sharia state Islamists in Pakistan long struggled for. The 1962 Constitution, drawn up under the dictatorship of Ayub Khan, offered almost an identical set of Islamic provisions and it too was short-lived and lasted as long as the regime itself could endure.

The third and current 1973 Constitution declared Islam as the state religion in Article 2 of the document alongside Islamic provisions similar to those found in both the 1956 and 1962 texts. But more was required to prove the state’s Islamic resolve. The Second Amendment of 1974 which rendered Ahmadis as non-Muslims arose out of this pressure and in a context of both Islamic opposition to the political leadership of then prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and his manipulation of Islam for political legitimacy. The Second Amendment was a defining constitutional moment for the precedents it set against religious minorities since it translated theological difference into legal and political exclusion. It also fixed the finality of the prophethood of Muhammad as a symbol of ongoing political and constitutional contestation. The Amendment was a disastrous moment for Ahmadis in Pakistan.

Nevertheless, these constitutional measures still failed to steer Pakistan towards an agreeable Islamic destination. An opposition coalition to Bhutto’s growing authoritarianism called for the installation of the Nizam-e-Mustafa (Order of the Chosen One), but this vision too was vague. Bhutto was overthrown and executed in 1979 and the dictatorship of General Zia ul Haq, which emerged in its place, sought to appropriate the Islamist cause (and some of its proponents). Zia promised to transform Pakistan into an Islamic state and his method was not so dissimilar to Bhutto in that it included measures which spotlighted the constitutional importance of Islam. Zia, for instance, made the Objectives Resolution a substantive and effective part of the Constitution. A notable point of departure however was Zia’s efforts to initiate a process of Islamising criminal, evidence, and taxation laws and install a structure of religious appellate courts. But this was contested since his Islamisation program was rather superficial, politicised vulnerable groups and designed to broadcast the need for Islamic legal reform without augmenting or limiting his own dictatorial powers.

Indeed, Zia’s Islamisation program and constitutional reforms sought to reign in state and political institutions under his control. The specific Sunni flavour of his Islamisation reforms was motivated to appease Sunni Islamists in a context of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, US-Saudi backed Afghan jihad and the growing Shia Muslim political consciousness in Pakistan in the wake of the Iranian revolution. Zia’s Islamic reforms should be seen more as a political instrument seeking to capitalise on and respond to regional and international developments then a genuine, broad or consensus driven Islamic agenda. A Sunni-bias in his Islamisation program, in other words, paid him handsome political dividends for his foreign policy and domestic political ambitions. And although his Islamic reforms are often characterised as puritanical, the Islamisation agenda was far more a manifestation of his politics than a demonstration of doctrinal coherence. While classical Sunni or Quranic doctrine may have provided some reference or inspiration for particular laws, it was politics and political considerations which would determine their amorphous and unusual shape. This meant that these laws sought to appease or address the goals and concerns of one group, while marginalising another, facilitating a process of in-group/out-group relations centred principally around sectarian and theological boundaries.

The infamous blasphemy laws were promulgated under Zia through changes made to the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC). These laws were drawn up not just to protect Sunni Muslim sensitivities through the criminalisation of the beliefs and practices of non-Sunni Islamic sects, it also laid the burden of blame on these sects for their supposed innate capacity to injure or enrage Muslim feelings simply through their existence or religious practice. Section 298-C of the PPC, for instance, stated that Ahmadis who, in ‘any manner whatsoever outrages the religious feelings of Muslims’, shall be punished with imprisonment and shall also be liable to a fine. The striking and fundamental design flaws of Pakistan’s blasphemy laws open the door for abuse, exploitation, stigmatisation, and the persecution of vulnerable or marginalised communities. Section 298-A (which is aimed at criminalising Shia Muslims and outlawing fundamental elements of their belief system) and Section 295-C (which relate to punishing derogatory remarks against the Prophet Muhammad) do not require proof of intention for an offence to take place. The vagueness of what constitutes a breach of Section 295-C renders this law an ongoing danger for religious minorities as their beliefs differ from foundational Sunni beliefs about the theological status of the Prophet.

While sectarianism and suspicion of minorities were present since the creation of Pakistan, historians have long noted that the policies, laws, and politics of the Zia era transformed Pakistan significantly for the worse. The Islamisation program he left behind has proved difficult to reform, let alone repeal. Intimidation and the threat of violence continues to silence critics of Zia’s legacies. The assassination of Salman Taseer, the former governor of Punjab, following his efforts to reform the blasphemy laws is a notable case in point. The troubling inheritances of the Zia era continues to facilitate the growth of religious intolerance and vigilantism, the rise of violent sectarian extremism, and a virulent and divisive discourse vilifying religious minorities (including minority Islamic sects) as active and hostile detractors, agents or fifth columns working towards the unravelling of an Islamic Pakistan. This view of minorities as villainous miscreants is not just a fringe position held amongst far-right Islamist groups but is often a stance emanating from the state itself. The government of Pakistan issued a pamphlet justifying the introduction of Section 298-C in 1984 on the basis that ‘The most sinister conspiracy of the Qadianis after the establishment of Pakistan was to turn this newly Islamic state into a Qadiani kingdom subservient to the Qadiani’s pay masters. The Qadianis had been planning to carve out a Qadiani State from the territories of Pakistan’. Ahmadis, in other words, posed a danger to both Islam and Pakistan. This discourse on minorities as enemies from within continues through to the present and has a direct relationship to the discourse of keeping Pakistan ‘Islamic’.

In 2014, the Supreme Court directed the government of Pakistan to constitute a National Commission for Minorities in order to probe into the ‘dismal state’ of minority rights and ensure that textual guarantees of rights matched empirical realities. The construction of this Commission, however, proved to be a contentious affair especially in negotiating its composition, jurisdiction and function. The government of recently former Prime Minister Imran Khan argued that Ahmadis should not have representation in the Commission. Noor-ul-Haq Qadri, Pakistan’s Federal Minister for Religious and Inter-faith Harmony Affairs, defended this position arguing that ‘Whoever shows sympathy or compassion towards [Ahmadis] is neither loyal to Islam nor the state of Pakistan.’ Ali Muhammad Khan, State Minister for Parliamentary Affairs, further labelled Ahmadis as ‘agents of chaos’. That Shia Muslims are Iranian proxies seeking to turn Pakistan into a Shia state remains a concerning discourse since the Zia period, and the ‘Sunnification’ of the Pakistani state is often an electoral promise of right-wing Sunni Islamist groups. There is also a growing campaign to declare Pakistan as a Sunni state and Shias as non-Muslims. Meanwhile, Shia, Hindu and Christian places of worship are frequent targets of terror, vandalism, and desecration. These communities face mounting safety and security concerns from radical or far-right Sunni militants.

The indiscriminate killing of minorities signals the message that non-Muslims have no place in an Islamic Pakistan and that their lives are dispensable. A contracting definition of who is a Muslim amongst these militant groups means that it is open season on more and more communities in Pakistan including the institutions and personnel of the state itself. The most disturbing manifestation of this development has been the growing intra-Sunni violence between Deobandi and Barelvi Muslims and the emergence of the radical Islamic State militant group which renders most Muslims in Pakistan as apostates.

Political opposition to the building of a Hindu temple in Islamabad in 2020 spotlights the spatial dimension of political exclusion. While the incident demonstrates the continued contestation over the place of minorities in the country, it also brings to the fore questions concerning the kinds of rights minorities have to space in an Islamic Pakistan. The debate further reveals a dissonance between constitutional guarantees afforded to minorities to practice and profess their faiths, and religious arguments that the construction of new places of worship of non-Muslims is impermissible and against the spirit of Islam and the sharia. The debate revealed that minorities continue to find themselves squeezed between Islam and the Constitution with little room or autonomy to manoeuvre in matters which profoundly impact their lives and are adjudged without consideration of their input. It also revealed ongoing ambivalence in the state’s governance of religious matters since arguments for or against the temple’s construction were all grounded on Islam. This also meant that what the Constitution had to voice would be in contest with various interpretations of Islam. What happens when Islam diverges from constitutional norms and prescriptions is a complex, manifold, and difficult question to resolve. The Supreme Court judgement in the Asia Bibi v. The State blasphemy case spotlights some of these tensions as the verdict defended Section 295-C on Islamic grounds even though the law continues to infringe upon the constitutional rights and protections allotted to religious minorities. Both the Court and then Prime Minister Khan argued that Section 295-C is the solution, rather than the cause, of blasphemy despite convincing evidence to the contrary. Khan has gone so far as to urge other countries to introduce blasphemy laws.

Concluding remarks

Religious minorities in Pakistan have been constructed as the ‘Other’ in the process of searching for and defining a collective sense of Islamic ‘Self’. But both the ‘Self’ and the ‘Other’ have proven to be unstable and contested categories since mapping the boundaries of theological tolerance between unbelief, heterodoxy and orthodoxy in Pakistan remains the subject of intense political contestation. Furthermore, as violence and coercion, especially through law, state policy, vigilantism, formal politics, and acts of terror, form the means to decide and institutionalise theological positions, the results are tenuous and fragile. The subsequent implication of these developments in Pakistan is that the parameters of who constitutes minorities continues to expand, while who or what constitutes the ‘Islamic’ fragments into further division and disintegration.

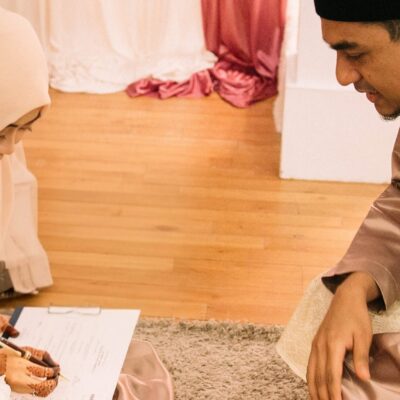

Image: Ashura Islamic holy day for Shia Muslims, Multan, Pakistan, 2021. Credit: thsuleman/Shutterstock.