The Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) decision-making system, or ‘consultative reporting system,’ is a complex process which, over the last decade or so has used academic opinion as a source of advice.

Our research looks at the changing role of academic opinion in the CCP’s decision-making system. We conducted in-depth and follow-up interviews in 2019-2022 using the snowball sampling method with six CCP officials engaged in the compilation of consultative information, nine scholars and three university administrators from different provinces.

The CCP’s consultative reporting system assumed its current form in 1985. The CCP’s provincial offices, Xinhua News, as well as direct reporting entities (zhibaodian)—such as selected local CCP general offices, state-owned enterprises, public and private institutions—submit reports daily to the Central CCP General Office (CCGO). Similar to policy proposals, a consultative report includes a brief description of an issue, suggested solutions, and identifies who could take action. The CCGO chooses and combines the material into classified journals such as the General Office Newsletter and Internal Reference, which are circulated among key CCP elites. Consultative reports are incorporated into policy or political actions via pishi, the written response or instructions of a decision-maker.

Beginning in the early years of the 2010s, the CCP expanded its decision-making mechanisms to accommodate policy recommendations from those outside CCP, in response to the increasing complexity of administration. Before Xi Jinping took the leadership of the CCP, non-CCP institutions were largely excluded from contributing to decision-making processes. Since the beginning of the 2010s, the CCP’s increasingly complex governance challenges have made it more difficult for its staff to provide up-to-date, comprehensive, and impartial policy recommendations. Reports from ministerial research institutions have frequently been criticised for being biased in favour of ministerial interests at the national level. Meanwhile, local CCP committees have thwarted important local policy proposals to conceal the local leadership’s incompetence from CCP elites. As a result, in the late 2000s, the consultative reporting systems became ‘rigid and slow’ even in relation to crisis situations and occasionally misinterpreting major national issues (interview with Subject Z).

Early in the 2010s, officials started incorporating scholarly findings into their decision-making process (interview with Subject Z). Academics are generally relatively removed from the competing interests of ministries and tensions between the central and local governments. In addition, scholars investigate topics from views distinct from those of the CCP institutions and apply various research techniques to generate more ‘scientific’ policy proposals.

The consultative reporting system was initially opened up for ‘new-type’ government-funded think-tanks. For instance, in 2015, the CCP Publicity Department established and managed 25 national high-level think tanks (guojia gaoduan zhiku), and their reports went directly to the CCGO (interview with Subject G). At the local level, similar structures have been established, for example, the central office of the CCP in Shanghai obtained information directly from university think-tanks established under the 2011 ‘Implementation plan of enhancing the social service capacity of knowledge in the higher education institutes of Shanghai.’

The participation of individual academics in policy consultation reflects the rising competitiveness among local CCP committees in terms of consultative reporting performance. Due to the CCP’s emphasis on receiving high quality information, the political relevance of the rankings of the local CCPs’ reporting performance has increased, which was conveyed at the 2019 National Forum on Information Work held by the CCGO (interview with Subject C). The message was clear: the CCGO is putting unprecedented emphasis on the performance of local CCP committees in providing high quality consultative reports (interview with Subject C). Low placement on the CCGO’s list suggests that local leaders are incompetent which may jeopardise their career opportunities.

The CCP has recruited an unprecedented number of academics outside government and CCP institutions since the early 2010s. In order to best meet performance targets, local CCP committees launched a campaign to maximise their sources of expert information and contributions from individual scholars are appreciated. The local offices of the CCP leverage this information as political capital with their central counterparts through pishi.

The goal of academic reports: receiving pishi

Due to the concentration of political and administrative power among CCP elites, when one leader issues a pishi in response to a consultation report, all relevant parties are required to comply immediately. The application of pishi typically results in contacts, finance, and ‘face’ (mianzi, professional respect) for local government and leaders. Therefore, local CCP committees generally have a strong incentive to submit reports that may attract pishi.

The political capital acquired via pishi may include permission to establish a new initiative or the right to exercise local discretion on certain concerns. Local government must acquire such permission to avoid exceeding their jurisdiction. As an example, the 2017 pishi by Prime Minister Li Keqiang on creating a National Botanical Museum in Yunnan’s capital Kunming mobilised the establishment of a series of significant projects locally.

‘Face’ (mianzi) may be supplied by academics to government connections via pishi. In Chinese official circles, mianzi is similar to a favourable impression of a particular person’s performance among their colleagues and superiors, which may help their career advancement. Similarly, an entity can earn mianzi in the consultative reporting system by achieving a high ranking under the CCGO’s scheme or gaining a high acceptance rate of its reports and attract pishi from elites of the CCP.

If scholars provide a large number of reports, they can become principal ‘face earners’ for the benefit of their contacts in the government. ‘[Local governments] have clearly realised the benefits of working with scholars. If you submit a lot of information, Laoda [the CCP elites] will remember you, and that adds to the mianzi of the local leaders’ (interview with Subject Z).

For party-state institutions that support think tanks, known as ‘leading institutions’ or ‘supervisory entities,’ the ‘return on investment’ for well-performing think-tanks consists primarily of the CCP elites’ approval, as they gain mianzi for the patrons and their leaders. In turn, the CCP patrons expand political funding for these think-tanks. ‘Why did those high-ranking officials appear at [discussion forums, ceremonies, etc. at the think tank]? Because we [think tanks] have been doing well [in providing consultative information] and they felt they gained mianzi by attending’ (interview with Subject W).

Likewise, funding and relationships with key government departments are essential resources to which the local government aspires via pishi. While implementing pishi, relevant ministry representatives frequently investigate the issues addressed in the report. ‘Ministries visit at least two to three times a year because of pishi on consultative information submitted by scholars (interview with Subject D).’ These events provide opportunities for local officials to secure ministry financing and develop professional ties, since ministries are more likely to invest in individuals and bodies that are already known to the CCP elites’ due to frequent pishi.

To achieve a high ranking in the CCGO’s consultative reporting system and garner pishi from the CCP elites, local CCP general offices must consistently provide reports that address the CCP elites’ concerns. Local CCPs are interested in academics because of their potential to recruit pishi. According to Subject C, the quantity of pishi given to academic reports is considerable. Among the highest-ranking cities in the consultative reporting system, in locations including Shenzhen, Hangzhou, and Xiamen, academics may have supplied up to 50 percent of pishi (interviews with Subject Z and W).

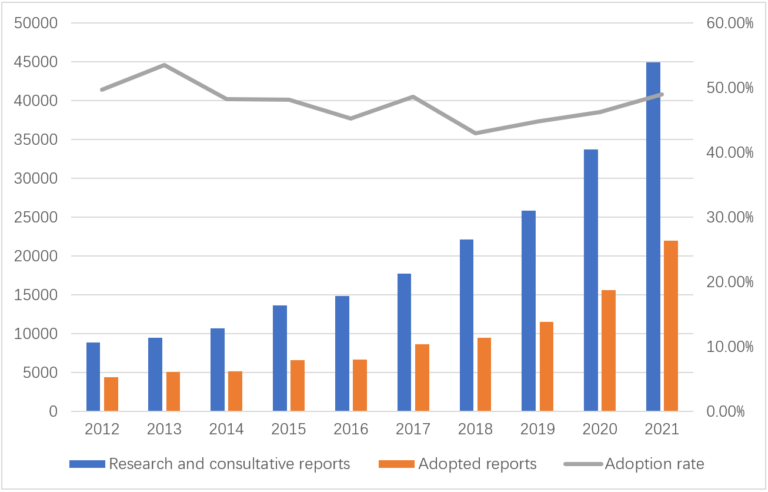

Consultative reports submitted by academics increased significantly between 2012 and 2021, according to data from the ‘Chinese Higher Education Humanity and Social Sciences Information Net (CSSN).’ Meanwhile, the number of academic reports adopted by local and central CCP committees or awarded pishi has increased since 2012 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Chinese Universities’ Consultative Reports, Adopted Reports and Adoption Rate, 2012-2021.

Data compiled from CSSN Statistics 2012-2021.

The number of consultation reports filed by Chinese universities rose by 405 percent between 2012 (8,878) and 2021 (44,874), showing an annual growth rate of 19.73 percent (see Figure 1). Meanwhile, the average annual growth rate of accepted consultative reports is 19.54 percent, rising from 4,407 pieces in 2012 to 21,967 pieces in 2021 which shows that the CCP has progressively incorporated scholarly perspectives into its decision-making processes.

However, between 2012 and 2021, the adoption rate of consultative reports submitted by university personnel has fluctuated. The average adoption rate is 47.6 percent and the adoption rate peaked at 53.49 percent in 2013 (see Figure 1). The adoption rate, however, dropped to a minimum of 42.9 percent in 2018; and while the numbers have increased since 2019, they didn’t return to the 10-year average in 2021. This trend indicates that obtaining pishi has become increasingly complex, although the total number of reports submitted by universities remains high. The findings are supported by an interview with Subject Z, who describes the leaders as ‘becoming increasingly cautious in giving pishi.’ Therefore, earning pishi through academic reports may no longer be sustainable for local CCP committees.

Chinese academia: aligned to the CCP’s thinking and needs

Participation in the consultative reporting system by academics has resulted in a number of changes inside Chinese academia. Previously, the relationship between Chinese academics and the government was that of client and patron, as the CCP and the government dominated China’s primary research funding, academic publication, and talent programmes. Chinese academics and their government therefore have a relationship of interdependence.

Since 2013, the CCP has included consultative reporting into academics’ performance evaluations, promotions, research funding, and talent programme applications. This tendency has resulted in a greater congruence between the academic community in China and the CCP’s ideas and needs. The CCP, the State Council, and a growing number of research institutes have evaluated academic achievement based on the number of consultation reports which have received pishi. In 2014, the National Office for Philosophy and Social Sciences specified that academics may utilise pishi from ministerial or higher-level leaders to waive the double-blind peer review by the National Social Science Fund (NSSF), which is a method of evaluating applications for NSSF projects. In 2018, the Ministry of Education included pishi as an assessment factor to the national talent programme ‘Changjiang Scholar’ (changjiang xuezhe). Pishi may also influence the ‘Ten Thousand Talents Program’ (wanren jihua), a national talent program managed by the CCP Organizational Department, which contradicts the program’s declared objective of eliminating bureaucratic interference in scientific research (interview with Subject W).

Since 2014, consulting reports by academics can attract monetary reward. Several research organisations decided that consultation reports that obtained pishi from members of the Politburo Standing Committee would be given up to 100,000 yuan (equivalent to 20,000 AUD). Reports adopted by the CCGO or the General Office of the State Council would be awarded between 15,000 and 30,000 yuan. These are substantial amounts in relation to the average annual salary of Chinese academics in 2021 of between 117,000 and 140,000 yuan).

Universities have also included pishi into their assessment standards. A Politburo Standing Committee pishi is comparable to a Q1 SSCI journal article (journals with an impact factor ranked in the top 25 percent among all journals listed in a given research category). In contrast, those approved by the CCGO correspond to a Q2 SSCI journal publication.

What this means for Chinese academia, which has grown more entwined with the political interests of the party-state, is unknown. Some contend that consultative information strengthens the Chinese academic community by exposing academic research to a broader and more powerful audience (interview with Subject Z). But an increase in academic consultative reports may reduce scholars’ available time to conduct research. In this regard, it is questionable whether the production of consultative reports is beneficial for the Chinese academic community.

Consultative information and academic research are not comparable. One key difference is that the CCGO only accepts topics that address pragmatic and urgent issues favoured by CCP elites, whereas academic research investigates a much broader range of topics. The second difference is the secrecy surrounding the editing and reviewing of consulting reports. As the contents of the leaders’ pishi are confidential, it is difficult to track the policy implications of the reports. Even when receiving pishi, the CCGO cannot always ensure that approved reports will have policy results.

The inclusion of Chinese academic institutions in the CCP’s consultative reporting mechanism has varied outcomes. Scholars who actively contribute to the production of consultative reports may find it simpler to advance their careers via pishi as opposed to academic output. On the other hand, the inherent distinctions between consultative reports and academic research made it difficult for academics to succeed at both. In this regard, it is challenging to conclude that involvement in the CCP’s consultative channel is advantageous to Chinese academics.

Conclusion

Since the early 2010s, academic viewpoints have been included in the CCP’s consultative reporting system as part of the ‘dig deep and reach wide’ effort due to the growing need for high quality policy proposals by the central CCP and the following performance pressure it passes onto its local equivalents .

The CCGO has since tied scholarly advice to the performance ratings of local CCP committees, compelling the latter to extend their existing reporting channels. Academics are valued owing to their independence from institutional interests and capacity to use a variety of research techniques to enhance ‘scientific’ decision-making.

However, the patron-client relationship between academics and the CCP has evolved into interdependency, with academics being able to provide political assets for local CCP leaders; which has also resulted in the academic ecosystem becoming closer to the demands of the party-state. Consultative performance is now completely incorporated into scholar evaluations, promotions, funding requests for research and award submissions.

Authors: Associate Professor Taotao Zhao and Ke Xiao

Image: Tsinghua University main building. Credit: Tagosaku /Flickr