Not all national constitutions deal with languages. But in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), both the official common language (Putonghua) and the officially recognised 少数民族(“minority”) languages are constitutional topics. These languages have been established by the various Constitutions from 1949 onwards as constitutive elements of Modern China, but there is a tension between these official languages of differing status.

What’s new?

I argue this constitutional concern with languages entered a new phase of utilising legal processes this decade, with a 2020 review and decision by the Legislative Affairs Commission of the National People’s Congress Standing Committee that regulations requiring schooling in the medium of certain minority languages were unconstitutional. (NB Google and others translate 法制工作委员会 as ‘Legal Affairs Commission’ but that was, in fact, the name of the Legislative Affairs Commission’s predecessor organisation, 法制委员会, replaced in 1983.)

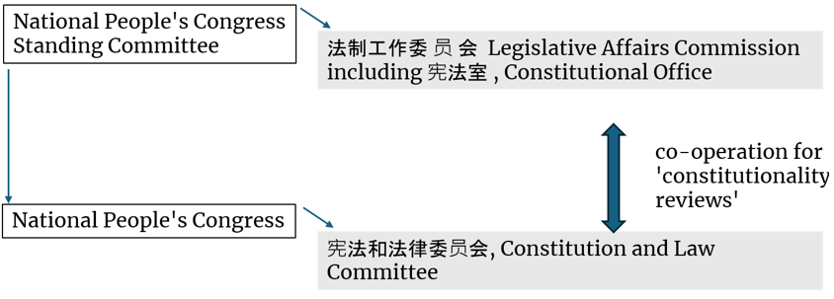

China has a written Constitution, but there is no court tasked with interpreting the Constitution or reviewing the constitutionality of laws. Rather, ‘constitutionality review’ is now undertaken by the 宪法室 (Constitutional Office) of the 法制工作委 员 会 (Legislative Affairs Commission), abbreviated as 法工委 in Chinese and LAC in English. The Legislative Affairs Commission works together with the National People’s Congress’s 宪法和法律委员会 (Constitution and Law Committee). (The National People’s Congress is the highest law-making assembly in China.) As illustrated in Figure 1, the Commission has the power to “推进合宪性审查” (“promote constitutionality review”).

Figure 1: Who reviews the constitutionality of laws in the PRC?

The first constitutionality review undertaken by the Commission concerned regulations about minority language-medium schooling. The Commission invoked Article 19 of the Constitution, which concludes: “The State promotes the nationwide use of Putonghua”. It was this part of the Constitution that the regulations were seen to deny; the Commission determined they were unconstitutional.

Meanwhile, Article 4 of the Constitution still provides that “All nationalities in the People’s Republic of China are equal. […] All nationalities have the freedom to use and develop their own spoken and written languages”. This relates to the 55 officially recognised minority groups and the 54 officially recognised minority languages. The Commission was not required to explain how it read Article 4 alongside Article 19.

A billboard depicting cultural diversity from Urumqi, Xinjiang, China, 2013. Credit: Author.

The Commission then submitted its opinions to the relevant authorities, seeking that they replace the unconstitutional regulations, which they did. (The Legislative Affairs Commission’s report dated 28 December 2022, Section 2, provides this update.) The immediate effect of its decision on the ground was a switch to teaching certain school subjects in Putonghua in the two jurisdictions where these regulations had operated, both in North China. I will return to the specifics of these regulations shortly.

With this review, the Legislative Affairs Commission added a new stone to the wall protecting Putonghua; a large, immovable stone. But the wall was already going up.

What’s not new? Policies juggling majority and minority languages

Well before the 2020 decision, there was the potential for clashing interpretations of “the right to learn and use the standard spoken and written Chinese language” in Article 4 of the National Law on Spoken and Written Chinese (中华人民共和国国家通用语言文字法 2000) and the similar Article 19 of the Constitution, on the one hand; and on the other hand, the “freedom to use and develop” a minority language found in Article 8 of the same national legislation and Article 4 of the Constitution.

Moreover, China’s national “主体性” (Subjectivity) or “主体多样” (Subject Diversity) language policy this decade explicitly prioritises strengthening the national language over linguistic diversity, so the Legislative Affairs Commission’s decision to prioritise Article 19 of the Constitution over Article 4 is unsurprising. The “promotion and popularisation of the state common language” is described as “the main line and direction of our language policy” and is said to “take precedence over ‘diversity’, diversity depends on the subject”.

This political and legal hierarchy is more explicit than language policy was before the 2020s, but there is a long-standing tension in China’s language policies between promoting Putonghua and promoting linguistic diversity. For example, in a study across the 2010s, my book analyses the developmentalist rationale that has long underpinned minority language policies and lowered the perceived value of minority languages.

This hierarchic national language policy is assumed by some commentators to be necessary because promoting the national language and reducing linguistic diversity is “a basic national policy that profoundly affects national identity and national security”. This assumption, that allowing people to use minority languages breeds secession, is not new despite politically stable bilingual/multilingual communities having been widespread across China. By contrast, the Zhuang case study in my research last decade reveals people identifying as both Chinese and Zhuang. (Zhuang is the name of China’s most populous official minority group and the language associated with it.) This concern with national instability along ethnic lines is reflected, too, in the 2018 addition of “和谐关系” (harmonious relationships) to those which the State “develops […] among all of China’s nationalities” as articulated by Article 4 of the Constitution.

Many language policy initiatives have focused on increasing the number of people literate in Putonghua and raising the standard of the Putonghua that people speak. In the last decade, the framing of ‘poverty alleviation’ through education in Putonghua became prominent. For example, the current rural revitalization plan states that “Teachers shall insist on using Putonghua to communicate with young children, encouraging them to speak Putonghua boldly in their daily lives and in games, and creating an environment in which they can communicate in Putonghua daily.”

There’s no dispute that the people classed as belonging to the 55 official minority groups are, overall, poor compared to people from the majority (Han) group. They are also more likely to be illiterate in either Putonghua or a minority language. These overall trends are borne out in my specific case study; Chapter 2.7 of my book compares poverty and illiteracy rates for the Han majority and the Zhuang based on Census data. But Zhuang people, at least, are also increasingly likely to speak Putonghua and regional Mandarin dialects in addition to or even instead of Zhuang language. It’s not clear to me that Zhuang language is a burden that needs alleviation; that is, one might question whether growing up learning Zhuang language causes poverty, and whether getting out of poverty requires its disuse. Could policy assist people to be both bilingual and richer?

Since 2015, there’s also been a “resource orientation” to the national language policy with which the Legislative Affairs Commission’s decision remains consistent. This national project is called 语保, short for 语言保护, the ‘Yubao’ or ‘Language Protection’ Project in English. But only some languages are treated as resources for further economic development, for instance because they facilitate international trade. There has been significant investment to increase and co-ordinate the number of university graduates with these language skills. Minority languages are not the focus of that investment, however, at least in my research context of South China, even though some of these languages are already spoken across borders, used locally in cross-border trade, and provide a head-start for their speakers when learning the related languages of the PRC’s southern neighbours.

By contrast, Yubao, as implemented in relation to minority languages, tends to mean the investment of time, personnel and resources into recording or documenting language varieties for archival purposes. The scale of this investment is said to be world-leading, but the point is to protect languages from being completely forgotten rather than protecting their ongoing, everyday use by living people.

In effect, Yubao is nationalising many diverse linguistic and cultural resources of minority peoples. The heritage resources it creates are disembodied, controlled by state institutions and available for the state to use in performing a local-affiliated identity or in place branding, amongst other uses. To build on an example from my 2010s research in the Guangxi Zhuangzu Autonomous Region, Standardized written Zhuang language is rarely displayed in public by anyone but government institutions and inaccessible to most would-be-readers because Zhuang literacy is not widely taught, and moreover because people are socialized to not expect public, written Zhuang. This form of the language, therefore, could be seen as a nationalised resource mainly used for place-branding Guangxi’s capital, Nanning, and constructing a local government identity. Zhuang and other minority languages are increasingly being documented and digitised, but if people are not also supported to continue using minority languages and passing them on to children, it’s not clear how these heritage resources will remain (a) linguistically and technologically accessible or (b) socially meaningful in the construction of minority identities or minority cultural practices in future decades.

This focus on preserving linguistic heritage rather than supporting lived multilingualism is part of a reduction across many fronts in the value accorded to, and the opportunities for, knowing and using a minority language. Those other fronts include shifts in bilingual education policy— some caused by the Legislative Affairs Commission’s review of bilingual schooling regulations and some occurring in parallel—and the Commission’s recent decision, reported in 2023, that regulations allowing for preferential employment in (unnamed) Autonomous Counties for candidates who answer recruitment exams in a minority language are inconsistent with the National Law on Spoken and Written Chinese.

In terms of bilingual education, there has long been national policy support for schools in some areas with high proportions of people from official minority groups to use both Putonghua and a locally common language. The exact form has varied across the country, with some schools teaching bilingually throughout secondary school while others include a minority language only verbally as a teaching aid, and just for the first few years of primary school.

Across the board, everyone has had to start studying some subjects in the medium of Putonghua from Grade 1. From 2021, this includes mandatory instruction in Putonghua for some of the pre-school curriculum, following the ‘Children Speak in Unison’ Plan (儿童普通话教育 ‘童语同音’ 计划). Pre-school itself is not mandatory but is publicly funded.

With Dr Gegentuul Baioud, I have elsewhere examined how Putonghua-medium preschool fits into the educational landscape of the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, as a case study. We expressed concerns about whether children will be able to master Mongolian sufficiently for the remaining school subjects taught in that language, given their reduced exposure to it. We also touched on the “despair and hopelessness” these shifts create, such as the Legislative Affairs Commission’s 2020 decision which specifically reduced Mongolian-medium education in Inner Mongolian schools.

What was deemed unconstitutional by the Commission, given bilingual schooling is allowed?

One of the two sets of regulations the Legislative Affairs Commission ruled unconstitutional was from the Standing Committee of the Inner Mongolia People’s Congress. The other set of regulations were from the Standing Committee of Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture People’s Congress in Jilin Province. The Inner Mongolian regulations had been in force since 2016 and the Yanbian regulations since 2004. It appears these regulations were previously uncontentious, but now the politics of language have changed.

Some of the commentary suggests the offending regulations required monolingual schooling in Mongolian or Korean. This is untrue. The reputable NPC Observer blog tracked down these regulations and noted that both allowed Putonghua to be taught as a language subject. The Inner Mongolian regulations also seemed to allow Putonghua as the medium of instruction in other school subjects, consistent with the bilingual schooling allowed by the national legislation about education (中华人民共和国教育法1995, see Article 12) and the Regional Ethnic Autonomy Law (中华人民共和国民族区域自治法 1984). As I have explained in my book (p.74), “schools may use a minority language in addition to Chinese, but they may not use a minority language instead of Chinese except in places within autonomous territories that meet certain criteria, and even then […] schools must ensure that higher-grade primary school and secondary school students learn Mandarin Chinese and that Putonghua is popularized”.

A different explanation from Chinese constitutional law expert, Wang Jianxue, citing a Gazette of the Standing Committee of the NPC, is that these regulations erred in providing merely that teaching “可以” (may) be undertaken in Putonghua. The amended 2021 regulations from Inner Mongolia bear out Wang’s analysis, in that they now say “应当” (must/shall) instead: e.g. Article 9, “the state common language and script shall be the basic language of education” (as translated).

Final thoughts

The effect of these various recent moves in language policies has been not simply to promulgate Putonghua, but to expand its domains of use and its prestige at the expense of minority languages and their speakers. There is a decreasing range of permitted applications of the constitutional freedom to use and develop a minority language, and of legitimate expectations for minority language support.

Scholars within and outside of the PRC have documented many phases of language policy since the 1950s’ radical turn towards mass literacy in minority languages and teaching local languages to cadres, to the 1960s’ distain and defunding, to the changes once the PRC ‘opened up’ in the 1980s. At that point, “bilingual education had renewed government and popular support in many parts of the PRC […] Since the early 1990s, however, the PRC’s language policy for minority education has gradually shifted […] to an integrationist approach that emphasises assimilation and unity.” My book has referred to the 2010s’ “trend towards securitized language policy that mistakes homogeneity for unity” (p.278). There’s now a reactive discursive trend in Inner Mongolia, at least, to emphasise national loyalty by “anonymising” the ethnic diversity of the region.

The Legislative Affairs Commission’s 2020 decision is consistent with these shifts in the 2000s and 2010s. It also reflects a focus on increased economic integration and a rationalisation of the nation’s human resources, aligned with the “National Language Capacity” approach the PRC now takes, the central concern of which is Putonghua capacity, evidenced at high levels including 2020’s Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Comprehensively Strengthening the Work of Spoken and Written Chinese for a New Era. The National Language Capacity approach itself builds upon the ongoing Yubao Project, commenced in 2015, and an overarching developmentalist rational that predates and underpins both. That is, updating regulations so that they no longer support the ‘unproductive’ learning of minority languages may well be seen as an uncontroversial means of improving the uptake of Putonghua to increase economic integration; why support schooling in languages that are no longer deemed important for economic development?

This assumes, of course, that people cannot bring their languages with them when they are integrating into the national economy and being lifted out of poverty. And it assumes that minority languages themselves have very little to offer the nation economically or as an element of social cohesion, rather than a force undermining it.

Moreover, while the current policy aspires to contain both the national and minority languages within a hierarchy, linguistic hierarchies are not stable. The prestigious and well-resourced languages at the top typically dissuade and displace the lower-ranked languages until they fall out of use. Moreover, linguistic hierarchies are generally co-constructed with persistent social, racial, geographic and economic hierarchies. Distinct ways of talking therefore become identifiable as new indices of social and racial groups, of urban or rural origin, of class and other such hierarchies. Even if the minority peoples of the PRC cease speaking minority languages in order to speak more or ‘better’ Putonghua, the common language is nevertheless unlikely to become entirely uniform across the nation, nor are its varied speakers likely to become equally valued.

Main image: A school bus in Beijing, 2023. Credit: Author.