The Islamic Republic of Pakistan has a Muslim-majority population of more than 96.4 percent. But it is also home to non-Muslims, who account for almost 3.64 percent of the population, according to official figures, although Pakistani Church leaders put the figure higher. Religious minorities include Christians and Hindus (mainly in the Punjab and Sindh provinces), Ahmadis, Scheduled Castes, Sikhs, Parsi and others. Christians and Hindus are the two largest minority groups and are concentrated in Punjab and Sindh Provinces, respectively. These religious minorities face significant socio-economic and political discrimination, which is well substantiated by various research studies.

Protections in law

The Constitution of Pakistan stipulates Islam as the State religion. It also includes some legal safeguards for non-Muslims to protect their rights and interests, including (but not limited to) Article 20 which establishes freedom to profess and manage religious institutions, Article 36 which specifically aims to protect the rights of minorities and Articles 51 and 106 which sanction reserved seats for non-Muslims in the National and Provincial Assemblies. Moreover, Article 25 calls for equality of citizenry irrespective of caste, color or creed.

However, Pakistan has a historical trajectory of promoting religious nationalism through constitutional change and there is a connection between religious nationalism and the weakening of the rights of religious minorities. For example, Ahmadis were defined as non-Muslims by a Constitutional amendment in 1974. The Constitutional definitions of Muslims and non-Muslims were inserted in Articles 260, 41 and 91 and disqualify non-Muslims from holding the positions of President and Prime Minister.

The exclusionary framing of Pakistani citizenship by the State driven instrumentalisation of Islam in policy and law, also calls into question the reality of equal citizenship and leads to the marginalisation of ethnic and religious minorities. For example, from 1978 until 2002, Pakistan had a system of separate electorates, which allowed non-Muslims to vote for Non-Muslims candidates only, depriving Non-Muslims of the same voting rights and constituencies as Muslims. These non-inclusive and hegemonic notions of citizenship can frequently cause minority groups to experience being relegated to the position of ‘second-class’ Pakistanis.

Pakistan has signed several international treaties on human rights that obligate the Government to protect the rights of disadvantaged groups, including religious minorities. But the reality on the ground is alarming, with little or no enforcement of implementing mechanisms to translate both national and international legal commitments into reality.

Reality on the ground

The persecution of members of the Ahmadi community—such as vigilante violence including killings, and burning of their settlements, graveyards, and places of worship— is ongoing and routinely reported in national newspapers. Allegations of blasphemy often turn into mob violence by extremist groups and can easily result in the accused being arrested. A recent example occurred in July, when an Ahmadi man was arrested after being accused of blasphemy for distributing free food at a Muslim religious event. The Ahmadi community boycotts electoral politics, neither casting their votes nor maintaining any relations with the State, which further creates a distance between the State and the community, hindering dialogue.

Christians also experience mob violence, particularly in the Punjab Province, such as in Jaranwala in 2023, Joseph Colony in 2013, and Gojra in 2009, which have included attacks on Christian houses and places of worship. Several reports by civil society organisations have indicated that blasphemy laws are often misused to settle personal vendettas and demand ransoms.

With rising incidents of religious intolerance and extremism in Pakistan, fear and anxiety have penetrated deeply across Pakistani society. Vulnerable minorities live with the ever-present fear of being maliciously accused of blasphemy in relation to unrelated disagreements with someone from the majority community. Calls for Pakistan’s government to repeal blasphemy laws have been made repeatedly by human rights organisations and minority representatives, but powerful Islamic political parties with a mass support base in majority cities have pressured the government not to make any changes. Violent street protests broke out in 2021 led by a religious political party favouring blasphemy laws.

Intersectional inequalities

The socio-cultural alienation of minority communities has resulted in spatial marginalisation, as evident from the ghettoisation of religious minorities in slums in both urban and rural areas. Christians and low caste Hindus often live in shanty settlements in back streets, far-flung villages, and semi-urban peripheries. This geographical marginality has a negative impact on socio-economic mobility and opportunities.

The right to socio-economic mobility of minorities is eclipsed, as I have previously illustrated, by discrimination such as caste-based occupation, gender, class, and religion. Women and girls are disproportionately affected. Religious conversion of non-Muslim girls and women to Islam is enabled by laws, legal procedures, and popular socio-religious understanding which allow marriage between a non-Muslim girl or woman and a Muslim boy or man, but not the other way around. Incidents of religious forced conversions of women of minority faith, followed by their marriages with Muslim men, are regularly reported in Sindh Province. Religious minorities in Pakistan have long raised their concerns about this at national and international forums.

Child marriages and forced marriages are especially difficult to prevent in poor communities where I conducted interviews in 2021 with six Christian women in Punjab from poor and broken families. The interviews showed that often the girls hoped for a more prosperous life but mostly end up facing stigmatisation and discrimination on account of their previous Christian identity. There is no legal distinction between a marriage of choice made by an underage girl from a minority group with a Muslim man and a ‘forced conversion’, which means that adhering to the age of consent can be evaded under Islamic provisions. The male patriarchs of minority communities fear the religious conversion of underage girls and often prefer to marry off young girls within their communities. This kind of religious patriarchy and cultural conditioning are played out on women’s bodies, commonly practiced in intra-community family structures, which restricts the autonomy of girls and women of non-Muslim communities to choose their husband and puts them in a situation of intersectional discrimination based on their gender, minority religion and low socio-economic status.

In June, Pakistan authorities raised the legal marriageable age of girls to 18 in the Islamabad Capital Territory, to bring it in line with the marriageable age of boys.

While this sends a positive signal to other parts of the nation, child marriages and forced marriages will continue and the move was opposed by the Islamic Council of Ideology, which declared the law illegal and un-Islamic.

Online spaces and social media

Religious discrimination has taken on a new dimension in online spaces and social media platforms, where hate campaigns, inflammatory language and abuse and disinformation targets minority communities with increased intensity. Human rights defenders use these spaces to push back and respond to extremist narratives, but the largely unchecked hate speech against religious minorities intensifies discriminatory behavior and incites violence against religious minorities.

Pakistan has seen a surge in digital hate, racism, gender-based violence, and sectarian and religious extremism. The Government of Pakistan has developed a strategy to prevent the spread of hate speech targeting individuals based on their religion, ethnicity or beliefs. The strategy includes maintaining a Database of Incendiary Hate Speeches, as well as the promotion of religious harmony and interfaith dialogue. However, online intolerance and bigotry goes unregulated partly due to political apathy and lack of monitoring mechanisms.

Discrimination in employment and education

Religious discrimination in the workplace is another significant issue faced by members of religious minorities in Pakistan. Religious discrimination in the workplace is not a legally protected category, so complainants have no legal redress. A sizeable majority of non-Muslims are employed in low-paid jobs, mostly concentrated in waste-removal work, which is despised socio-culturally and adds another layer of social exclusion and caste-based discrimination. A commonly-used epithet is ‘Chura’, a term which is has historically been used to refer to outcaste groups in the Indian sub-continent, and presently used to degrade and disgrace low caste groups for their intergenerational association with dirty work. This prejudice hugely contributes to their marginalisation.

Caste is a historical category through which social stratifications and exclusions are materialised and reproduced in Pakistan and across South Asia. The State of Pakistan denies the prevalence of caste hierarchies and prejudices by promoting an Islamic identity that contributes towards the erasure of caste from the political discourse in Pakistan. The Pakistani State espouses egalitarian values of Islam that do not allow any distinction based on caste, colour and creed. However, the reality on ground is that caste discrimination is pervasive. Used as a social identity, caste is a significant determinant in contracting marriages, mobilising local politics, and maintaining social status. In contrast to the political mobilisation and political agency employed by low caste communities in India, Pakistan has not witnessed the visible articulation of low caste-based identity politics by grassroots communities.

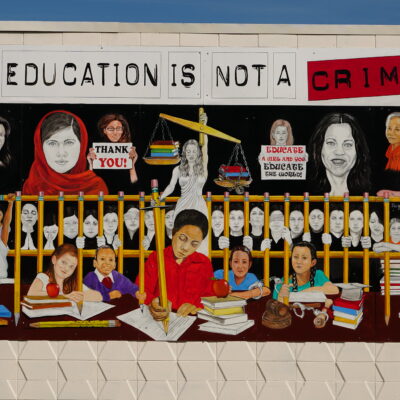

Minorities also face discrimination in educational institutions and Pakistan’s education system is does not adequately support religious pluralism and harmony. Several studies pointed out that educational curricula have ‘otherised’ religious minorities in Pakistan and also act as a catalyst towards other forms of exclusion, discrimination, and aggression that minority youth face within schools and in the community.

Weak political representation and policy change

Political representatives from religious minorities are accommodated in parliament through reserved seats, as set out in the Constitution: 10 out of 336 seats in the national assembly and four of the 96 seats in the Senate; as well as 24 seats in total in the four provincial assemblies. Elected political parties nominate members for the reserved seats on the basis of the proportion of the number of seats won in the parliament. As of 2022, there were 4.43 million registered voters from religious minorities, but no institutionalised selection mechanisms have been put into place by political parties to choose candidates from minority communities. Only those who are close to the leadership of the political parties get the privilege of being selected. This situation excludes more independent candidates, such as those who have political support from their communities.

Important issues affecting religious minorities are therefore left unaddressed. For instance, the Christian Divorce Law 1869 specifies that the only ground for divorce is adultery and in the Hindu community, inheritance matters are governed by the Hindu Law of Inheritance Act 1929, which gives preference to male relatives over female relatives of the deceased and further strengthens male patriarchal privilege. Lack of personal laws for religious minorities leaves family matters such as marriage, divorce, child custody and inheritance subject to misogynist socio-cultural norms which presents another barrier within the community to navigate. In addition, as mentioned earlier, issues and concerns about the misuse of blasphemy laws in Pakistan and mob violence against the settlements of religious minorities have not been addressed.

The Federal Government of Pakistan has a Ministry of Religious Affairs and Interfaith Harmony. However, the ministry focuses on organising religious activities for members of the majority community and sporadically grants scholarship support for students of religious minorities. Provincial governments have specific departments for minority affairs, but they have also been ineffective.

Conclusion

This year, the Government of Pakistan passed a bill to constitute a National Commission for Minority Rights, a statutory body given a mandate to safeguard minority rights. It may help give visibility to minority voices in the higher echelons of the government-run institutional structures. However, whether it’s effective in preventing the violation of minority rights depends on the level of resources allocated to it, whether its members are selected in a transparent way and how committed they are to enforcing minority rights.

Equality for all is supposed to be guaranteed by the Constitution, however translating these protections into concrete realities requires significant change at many levels. There needs to be sustained enforcement of minorities’ rights and better representation of religious minorities in mainstream political parties. Pakistan also needs to radically alter socio-cultural discourse on religious minorities. Concrete measures could include teaching religious harmony in schools, developing monitoring mechanisms to ensure swift response of the police to mob violence, providing judicial redress for the victims of mob violence, regulate and penalise hate speech against minorities on social media, introduce amendments in the personal laws of religious minorities to provide them fair access to justice and require political parties to elect deserving candidates to reserved seats in the parliament.

Main image: Protestors, including the author, at a rally in Pakistan in 2007. Credit: Author.

An error relating to a date was corrected after publication.