Taking a break from the rich conversations during the 2024 Association for Asian Studies-in-Asia conference in the Indonesian city of Yogyakarta, we take a taxi to the new location of the Pondok Pesantren Waria Al-Fatah. A pesantren is an Islamic boarding school, typically reserved for cisgender men and women looking for religious education. Al-Fatah, however, is unique because it was established specifically for waria, a compound of the Indonesian words wanita (woman) and pria (man). The term roughly translates as ‘transgender woman’ and is used to describe various forms of trans femininity. Al-Fatah’s previous leader Shinta Ratri passed away in 2023 and her friend Yuni Shara now leads the pesantren.

Amidst our conversation about this new space and sharing memories about our previous encounters, a group of American tourists arrive. They are visiting as part of an alternative tourist agency trip to explore hidden spaces during their holiday in Indonesia. Around 10 to 12 tourists, mostly older than 60, come as a group to learn about the practices of Muslim waria. After an explanation of the goals of the space led by Yuni Shara the tourists have an opportunity to ask questions. The visitors’ inquiries, ranging from the structural challenges faced by Indonesian waria to comparisons with queer youth in conservative states of the USA, are asked respectfully, but perhaps reveal a lack of understanding about unequal power dynamics.

The presence of this group leads us to reflect on what it means for this marginalised religious community to become an object of cultural consumption. Their identities as both waria and Muslims are performed in front of an audience that is led by a tour guide acting as the translator between two very different groups. How is their ‘authenticity’ curated for this external audience consisting mainly of Christian American heterosexual couples? In a national climate where anti-LGBTIQ+ rhetoric continues to grow, the pesantren’s self-commodification seems to act as a strategy of economic survival. To what extent do these visits risk reproducing orientalist constructions of the ‘exotic Muslim transgender other’, even when they might be framed as solidarity?

The encounter at the pesantren waria also reveals the emergence of a queer-inclusive Muslim counter-public in Indonesia that we seek to map in this article. Our reflections are shaped by our established relationships with queer Muslim communities in the archipelago. As queer researchers (with Diego being a gay Spanish researcher and Amar identifying as a queer Indonesian transgender Muslim man), our presence was welcomed through an ongoing engagement with the spaces we visited. Our findings draw on ethnographic fieldwork, including interviews, digital ethnography, and participant observation. Amar has been an active member of the pesantren since 2022 and visits every week on Sundays to teach Qur’an and facilitate discussions on inclusive Islam. He has also been invited as a moderator and helped design the pesantren’s strategy.

Rooted in the value of raḥmatan lil-‘ālamīn (‘mercy to all creation’), an increasing number of actors are reworking the social meanings of Islam through lived practices, reinterpretations, and grassroots spaces that centre queer agency. How do queer Muslims in Indonesia navigate spaces of religious belonging and public scrutiny, and how do their physical and digital encounters (from homes and classrooms to online platforms and tourist settings) reshape their visibility and lived narratives? An intersecting set of forces (including, among others, familial frameworks, educational systems, mainstream media representations, physical spaces, theological debates, and economic interests) mediate how these individuals negotiate visibility, safety and religious legitimacy. How might these everyday religious micro-politics reshape, even if incrementally, national debates over whose Islam will define Indonesia’s moral future?

Living rooms and classrooms

Across the world, home is usually the first place where we internalise religious, gender and sexual norms. In Indonesia, many of the LGBTIQ+ people we spoke with as part of our research described how their family home was where they first heard their parents describe gender variance as haram (forbidden by Islamic law). These lessons are often reinforced at public schools and pesantren, where religious stories are often used to condemn LGBTIQ+ identities. Reflecting on their education, 36-year-old non-binary Satu (all names of interviewees are pseudonyms to protect the anonymity of participants), told us that:

‘One day I had to memorise the story of the Prophet Lut. I thought it was right, that gay people were cursed. If you are a little kid and your teacher is indoctrinating you like that, you’re like, ‘wow, we cannot argue against it.’’

Other LGBTIQ+ Muslims indicated that, even though they never came across LGBTIQ+ inclusive statements from their teachers, they also never heard such homophobic interpretations. However, classrooms, too, carry emancipatory power since memorising verses equips students with tools they can later deploy against exclusionary readings.

Domestic experiences growing up in religious families can also be very varied. While some family members expressed rejection of and were even violent when our interlocutors disclosed their identities, others continued to accept and embrace their children disregarding any religious LGBTIQ+ condemnation. As one of our interlocutors shared regarding her journey as a waria:

‘[When I came out] there were no expressions of shock, because we all grew up together, so my sisters and my parents knew me already because since I was a child I was like a woman, wearing skirts, playing feminine games, and dolls. (…) I feel lucky to have a family who can accept me.’

When considering these issues, it is important to distinguish between patriarchal exegesis and the everyday experience of faith and belief, which reveal very different approximations to what being LGBTIQ+ and Muslim constitute.

Media and technology

While domestic spaces and school classrooms provide an entry point to reflect on what it means to be LGBTIQ+ and Muslim in Indonesia, devices such as computers and smartphones have increasingly enabled challenges to normative religious interpretations. Earlier LGBTIQ+ generations found their role models in variety-show icon Tessy or trans presenter Dorce Gamalama. Today, role models and progressive narratives often arrive via online forums, TikTok and Instagram videos. For example, progressive ustadz (Islamic scholars) dissect the story of Lot through online articles, arguing that the sin found in the people of the biblical cities of Sodom and Gomorrah was due to coercion, not consensual homosexual love.

Digital activism has become a mobilising force among the queer Muslim community. Online platforms act as networking spaces to find queer religious communities and exchange ways to campaign for inclusive narratives. Several new collectives have strengthened their community base through social media. For example, Narasi Toleransi and the Youth Interfaith Forum on Sexuality (YIFoS) have initiated meeting spaces and educational content based on the experiences of queer individuals themselves. Additionally, Pelangi Nusantara is an LGBTIQ+ group that often explores Indigenous pre-colonial gender and sexual expressions to challenge the belief that gender and sexual diversity is a Western ‘export’.

IQAMAH (Indonesian Queer Muslim and Allies), which defines itself as ‘a safe faith-based space’, was initially created as a weekly online gathering for individuals interested in discussing Islam and queer acceptance. The organisation has held several online courses on Islam, gender and sexuality, with facilitators who identify either as queer or as allies, including activists and professors from Islamic universities. They have also published a digital open-access ‘zine entitled ‘Perjalanan Menemukan Rumah’ (‘The Journey to Find Home; Fragments of Collective Works on Faith, Bodies, Gender, and Sexuality’), which includes poetry, short stories, comics, and articles written by 27 different authors. Unfortunately, IQAMAH has been inactive since late 2023 due to constant online harassment from conservative groups.

Further support from non-LGBTIQ+ allies can be found in online spaces from individuals and organisations. For example, the writer and researcher Masthuriyah Sa’dan has turned her social media account into a space for inclusive queer campaigning. When she released her book Sejarah Waria Yogyakarta (‘The History of Yogyakarta’s Waria’), published by the State Islamic University (UIN) of Yogyakarta, the launch was made public and received support from her university colleagues. Another example of allyship can be found in Kabar Sejuk, an online platform that explores human rights and diversity in Indonesia, arguing that religious institutions must include queer individuals.

Queer religious geographies

Digital connections and alternative exegesis often crystallise in physical spaces. The Pondok Pesantren Waria Al-Fatah is one such example. Here, Muslim waria receive weekly lessons on Islamic practices from kyai (religious leaders), recite Qurʾānic verses together, debate ritual purity with religious leaders and scholars from Islamic universities, and get together to organise charitable activities. Such a geography also acts as an economic project. The pesantren’s willingness to host the tourist group described above, however awkward, helps pay rent and support the waria members. The pesantren currently receives financial support from the ITF (International Trans Fund), and they have developed creative solutions to generate income by selling books and souvenirs to visitors. Commodification becomes a survival strategy and, paradoxically, a form of dawah (proselytism) since tourists leave with a narrative that queerness and Islamic faith can cohabit. The risk of exoticisation is an issue to consider, but the waria hosts themselves have the power to decide what is shown and withheld, preserving their agency. Complementing this example, other Muslim waria prayer groups meet regularly across Javanese cities such as Surabaya.

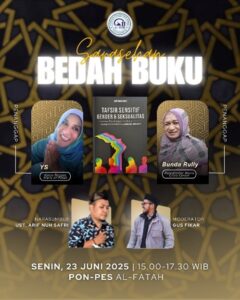

A poster from a book launch event for Tafsir Sensitif Gender dan Seksualitas. Credit: Authors.

At the national level, the Young Queer Faith and Sexuality Camp, run by YIFoS, convenes young Muslims, Christians, Buddhists and Penghayat Kepercayaan (Indigenous Faith) for a week to explore religion, gender, and sexuality. Typically, the camp has hosted around 30 participants each year, though it will not take place in 2025 due to a funding freeze. Participants combine tafsir (interpreting the Qur’an) workshops during the day with dangdut (a popular genre of Indonesian dance music) karaoke at night. These camps provide practical tools to comfort a marginalised youth while equipping them to challenge discrimination with religious arguments when they return to their home towns. Narasi Toleransi, the network introduced earlier, was established by the camp’s alumni network and has grown into an active digital space for queer activism at the intersection of faith and inclusion. They hold queer-affirming interfaith events and campaigns and play a key role building interfaith queer leadership. Each year on IDAHOBIT (the International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia), Narasi Toleransi invites religious leaders to publicly share their support for queer communities and condemn discrimination in the name of religion.

These queer religious geographies are not only spaces initiated by LGBTIQ+ people, but also by Muslim organisations that are supportive of them. For example, the eco-conscious pesantren Misykat Al-Anwar combines environmental activism with inclusive faith practices and welcomes queer Muslims who are looking for safe spaces to pray and participate in dialogue. In Cirebon, a city known for its rich Islamic boarding school tradition and progressive Muslim thinkers, there is a growing presence of queer-friendly religious activities too. These diverse spaces are reshaping how religion and queerness co-exist in supportive ways.

Local Islamic tradition

Progressive Muslim scholars and religious leaders have responded to anti-LGBTIQ+ discourses by framing their arguments in local traditions of diversity. They often refer to Islam Nusantara, the various forms of Islam that have developed across the Indonesian archipelago (Nusantara), to justify their statements. This archipelagic version of Islam promoted by influential Islamic organisation Nahdlatul Ulama celebrates the differences that local forms of living Islam reveal across the country. As a professor of Islamic Studies at Fahmina Institute, told us:

‘Islam in West Java is different to Islam in East Java. Islam in Indonesia is based on that locality (berbasis lokalitas), on the local traditions that exist here. Islam is blended with the elements of acceptance (elemen penerimaan) emerging from local traditions.’

The late chairman of Nahdlatul Ulama and former Indonesian president Abdurrahman Wahid, also known as Gus Dur, represented this philosophy. His followers in the Gusdurian Network (Jaringan Gusdurian) have been implementing diversity and inclusion programmes, grounded on the Indonesian national principle of Bhinneka Tunggal Ika (‘Unity in Diversity’). The network, led nationally by his daughter Alissa Wahid, is present across Indonesia through more than 155 local groups, as well as abroad in Malaysia, Iran, Thailand, and England. Shinta Nuriyah Wahid, his widow, also plays an important role in strengthening pluralism. Since 2000, every Ramadan, Shinta travels across Java leading sahur keliling (sahur touring), the ritual of waking people for the pre-dawn meal (sahur), visiting more than 30 locations including churches, mosques, Ahmadi and Syii centres and other spaces where marginalised communities live to promote living in harmony. Gender and sexual minorities are invited to these spaces where, for example, marginalised people can listen to Shinta’s speech and share experiences of discrimination such as people living with HIV/AIDS having difficulty accessing healthcare.

Theological work by Indonesian Muslim scholars and queer Muslims themselves has been a key source of inclusive religious exegesis. One example from history is the case of Vivi Rubian, a trans woman who, in 1973, filed Indonesia’s first gender confirmation legal petition. Her case received public support from one of Indonesia’s most respected Qur’anic scholars, Buya Hamka. Speaking at the hearing, alongside Christian priest Eka Darmaputera, Hamka stated that ‘Islamic teachings guide us to use our knowledge for the welfare (maslahah) of humanity. Legal efforts to change the birth certificate from male to female, in Vivian’s name, does not contradict God’s law and aligns with Islamic teachings that prioritise human welfare.’

A growing body of theological work by scholars who are also activists for women’s rights is reshaping how Islam is interpreted concerning gender and sexuality drawing upon Indonesian Islamic tradition. Key publications by Islamic scholars include Fikih Seksualitas (Muhammad et al., 2011), Santri Waria (Masthuriyah Sa’dan, 2014), Benang Kusut Fiqh Waria (Muiz, 2015), Mengupas Seksualitas (Mulia, 2015), Memahami Keragaman Gender dan Seksualitas (Safri, 2020), Spiritualitas Waria (Sa’dan, 2022), and Tafsir Sensitif Gender & Seksualitas (Safri, 2025). Building on this, queer Muslims, at times in partnership with allies, have also authored theological works that engage with questions of gender and sexuality. These include Seksualitas dan Agama: Dialog tentang Tubuh yang Terus Tumbuh (Anam & Napitupulu, 2019), Tafsir Progresif Islam & Kristen Terhadap Keragaman Gender dan Seksualitas (Alfikar, 2020), Islam dan Tubuh-tubuh Queer (Alfikar et al., 2022), and Queer Menafsir (Alfikar, 2023). These books have reached readers outside academic and LGBTIQ+ communities and have been launched in both Islamic institutions and Christian spaces.

Allies of LGBTIQ+ Muslims have varying strategies for advocacy. Some prefer discrete conversations with village kyai (local experts on Islam), while others push for bolder public challenges to theology that describes homophobia as sin. Both groups, however, share a language rooted in the Islamic concept of keadilan (justice) and Indonesian diversity rather than relying on Western rights discourses. This localisation, linking LGBTIQ+ inclusion to local values, is a strategic tool to reduce potential backlash and invite local Muslims to approach mercy as orthodoxy.

Despite progressive voices, LGBTIQ+ inclusion continues to be threatened. The 2022 Criminal Code criminalises all extramarital sex and allows local governments to police ‘public decency’. These provisions have been criticised by activists and scholars, who argue that they can be used selectively against LGBTIQ+ individuals. Under the current presidency of Prabowo Subianto, Indonesia is witnessing a shift toward the marginalisation of queer people. In this context, in West Java, Governor Dedi Mulyadi, has enforced hardline policies that reflect the authoritarian style of Prabowo. The regent of the West Javan town Cianjur, Muhammad Wahyu stated in May that ‘If there are indeed indications of LGBT they will also be given guidance’ at military barracks. Meanwhile, in Aceh, where Sharia law is enforced, queer communities continue to face violence. In February, Sharia police arrested four men accused of sodomy and raided a house where a transgender woman was living with her partner, illustrating the ongoing criminalisation of LGBTIQ+ lives.

There is a possibility that confected moral panic about LGBTIQ+ will be used as a political tool to distract from problems such as corruption, as has happened before. The LGBTIQ+ community and their allies are also trying to combat anti-gender movements in other nations, which can negatively affect local discussions and policies. The question is no longer whether Islam can accommodate LGBTIQ+ Indonesians, but whose interpretation will continue to shape the nation’s religious trajectory. Amid the increasing influence of Wahabi voices bringing more conservative approaches to Indonesian Islam, and in the shadow of populist politics and moral panics, a queer-inclusive Muslim counter-public rooted in the notion of rahmahtan lil alamin (‘mercy to all creation’) is drafting an answer slowly but steadily.

Authors: Amar Alfikar and Dr Diego Garcia Rodriguez.

Main image: Students and faculty from an Islamic University at a dialogue event at Pondok Pesantren Waria Al-Fatah, 2025. Credit: Al-Fatah.