At the end of the Second World War, numerous Japanese women who resided in colonised areas of Imperial Japan, particularly Manchuria, were subject to sexual violence at the hands of Soviet troops and colonised local residents.

When the women returned to Japan, the Japanese government directed officials to perform abortions on those who had become pregnant, including on those in very late term pregnancy. In some cases, the government enlisted help from civil society groups.

There remains a collective silence among those involved, especially among the victimised women. There has also been a dearth of academic investigations until very recently: the few exceptions include works by Lori Watt, Inomata Yusuke,[i] and Yamamoto Meyu.[ii]

The women’s silence, the state’s silence as well as public ignorance on this issue can be seen as indications of a lack of democracy in post-war Japan.

Sexual violence against Japanese women in Manchuria

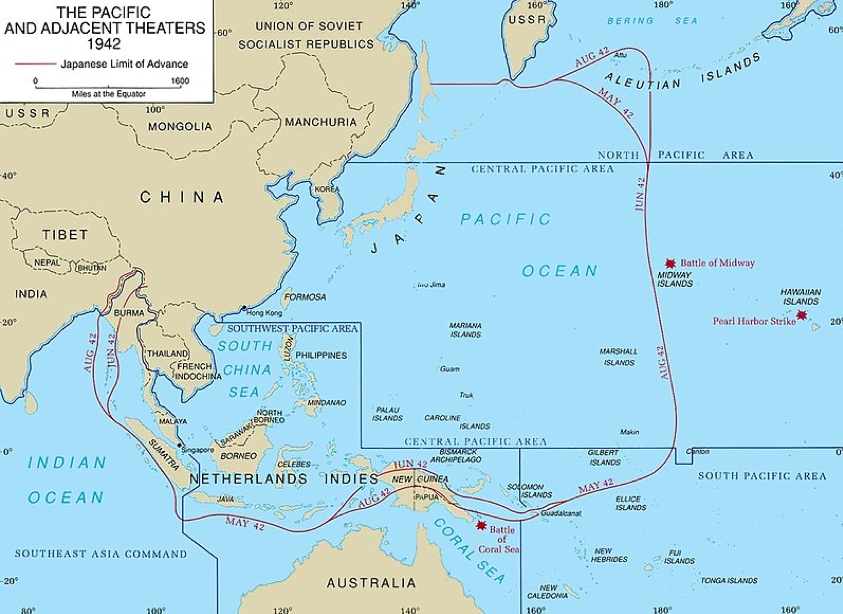

At the end of the Second World War, approximately 6,600,000 Japanese citizens, almost ten percent of the national population, were overseas, and almost half of these were civilians. More than eighty percent of these civilians resided in colonised areas of Imperial Japan (1868―1947), particularly in Manchuria,[iii] following the then Japanese government’s migration policies begun in the early 1930s.

They began to repatriate shortly before the surrender of Japan in 1945, when the Soviet Union suddenly attacked the borders of northern Manchuria and invaded on 9 August. Overseeing this massive movement of people came to be the purview of the Supreme Command of the Allied Powers (SCAP), which in October 1945 appointed what was then the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan as the responsible agency.[iv]

The experience of repatriation depended on where the Japanese had settled. For those who lived in the Soviet zones, such as Manchuria and the northern Korean peninsula, what could be called a ‘forced repatriation’[v] was experienced. It involved violence like pillaging and mass killing, perpetrated by Russian soldiers and also by the local people the Japanese had colonised.[vi]

Japanese women experienced significant sexual violence. The perpetrators committed sporadic rape and detained groups of women for a period of time to rape them repeatedly. In some cases, women were offered to the perpetrators by the Japanese community or their group leaders in exchange for guarantees of the group’s safety. Some women were reported to have offered themselves to protect their groups, families, or younger peers.[vii] There is no accurate record of the total number of victims of sexual violence due to the chaotic circumstances at the end of the war. Approximately 223,000 civilians residing in the Soviet zones died, mostly within one and a half years after 9 August 1945.[viii]

The response of the Japanese Government

The transportation of Japanese citizens repatriated from Manchuria started in May 1946, and most arrived in Japan by the end of 1947.[ix] At each receiving port, a regional repatriation office was established under the administration of the Ministry of Health and Welfare.

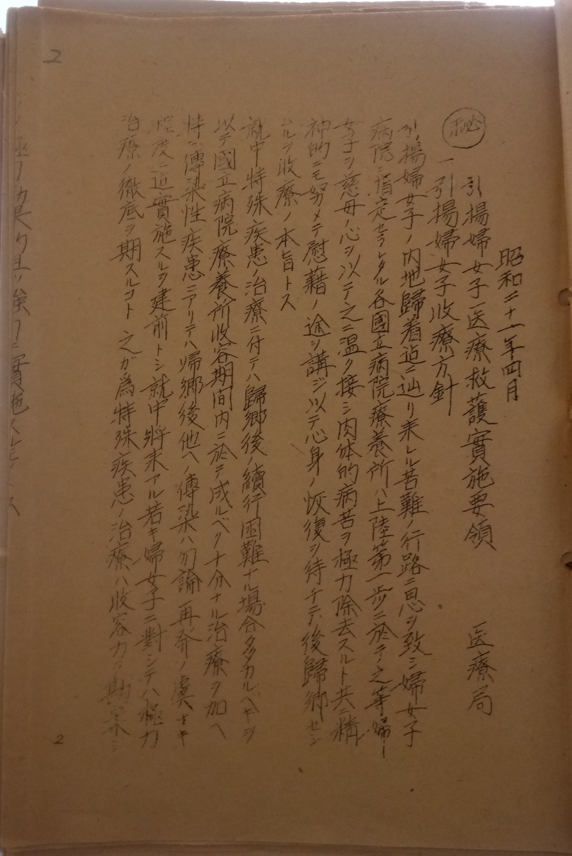

Because the mass violence against women in Manchuria was a known issue at the time, in April 1946 the Ministry of Health and Welfare issued Medical Order No. 151: Regarding Medical Aid for Female Repatriates from Manchuria and Korea.[x] This order directed each regional repatriation centre to establish a medical facility and a female counselling office for women who were ‘under extremely miserable situations’.[xi]

An appendix to the order, the Outline of Operating Medical Aid for Female Repatriates (Figure 1), required that officials ‘make every effort to abort the pregnancy of those pregnant women who are not suitable for regular labour for some reason’.[xii] The order gave no specifics as to what constituted ‘regular’. Abortion was generally prohibited with very limited exemptions under Japan’s penal code at the time.[xiii]

Figure 1

While the order itself was ambiguous in its aim, in 1987 a former member of the medical staff at a regional repatriation centre stated that there were two specific goals: preventing the spread of venereal disease and preventing ‘births of children who are contaminated by foreign blood’.[xiv] This indicates that the aim of the medical order was primarily to quarantine in two senses: in terms of public health; and ethnocentric ideology in pre-war Japan, which emphasised maintaining the biological ‘superiority of ethnic Japanese’.[xv]

Due to strict requirements of confidentiality set out in the order, there is a lack of recorded detail on the medical treatment of female repatriates who had experienced sexual violence, including the number of women involved. At the Sasebo and Hakata repatriation centres, however, the civil society groups who were involved in running medical facilities and female counselling offices archived reports, took photographs, and later spoke of their experiences publicly. I will focus on the case of the Sasebo centre, to which a large women’s group was attached.

The involvement of civil society groups – the Sasebo Tomo no kai

In 1946, the responsible officer of the administration of the governmental repatriation project contacted his old friend Hani Motoko to ask for her help with the project.[xvi] Hani was the founder of one of Japan’s oldest women’s magazines, Fujin no tomo (Women’s friend), and its readers’ organisation, Tomo no kai (Friendship societies). Most Fujin no tomo readers were wives and mothers from middle-class backgrounds, and Tomo no kai was an economically and politically independent organisation from its foundation in 1930.[xvii]

In the pre-war period, Hani Motoko and Tomo no kai had often cooperated with the Japanese government to disseminate their skills and ideologies in managing the sphere of domestic life,[xviii] thus aligning themselves with the state.[xix] Because of their political position and well-known volunteerism, Hani Motoko was asked to send members of the Tomo no kai’s Sasebo branch to the regional repatriation centre.

While Tomo no kai members aimed to ‘protect the women’,[xx] they were expected to assist the state’s ethnocentric quarantine by conducting screenings and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases, as well as assisting in the termination of pregnancies that were the result of sexual violence.[xxi] In addition, they were actively involved in providing vocational training for the victimised women while they were in recuperation.

In the 1970s, Nishimura Fumiko, a representative of Tomo no kai, recounted their tasks and testified that Tomo no kai members had mixed feelings in fulfilling their duties.

Because we are mothers beyond national boundaries, we had very complex emotions toward those lives [lost by abortions]…I have never forgotten it to this day.[xxii]

It is unclear whether the Tomo no kai women were aware that the victimised women might have had similarly conflicted feelings about their pregnancies and might have thought of themselves as mothers too.[xxiii]

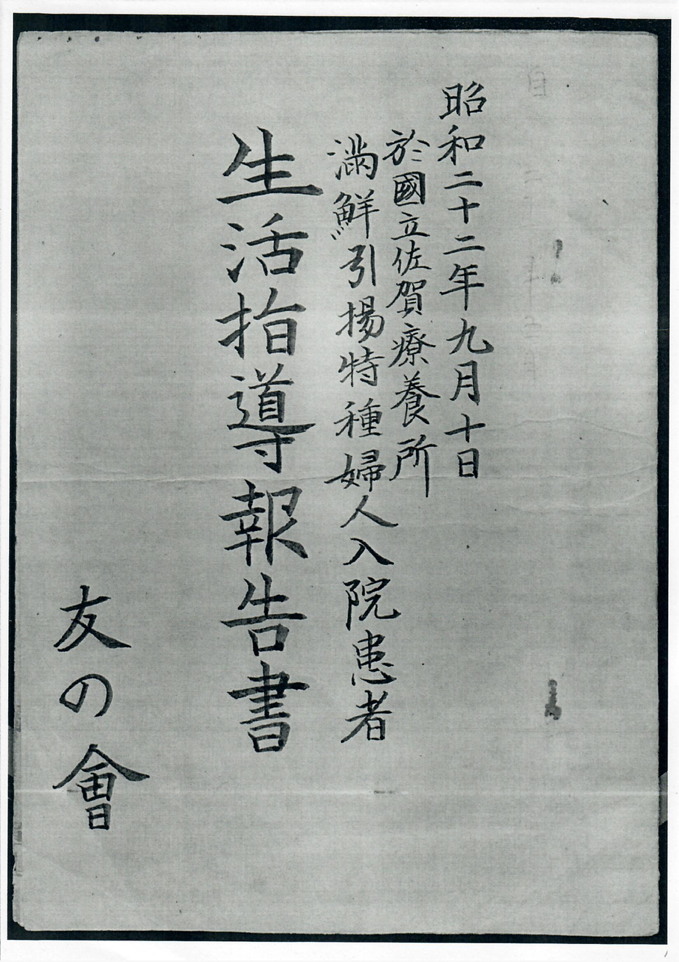

A record of Sasebo Tomo no kai activism, The Report on Daily Life Guidance, indicates that the Tomo no kai members acted as mentors of a ‘self-disciplined and diligent lifestyle’[xxiv] for the repatriated women. According to available documents, the Sasebo members muzzled their emotions in the belief that the medical treatments were necessary to help the victimised women and to follow the government’s direction. One member remarked that they understood that the purpose of the female counselling office was to quarantine rather than help women but insisted, ‘In the end, it was a good measure for victimised women’.[xxv] After two years of work at the repatriation centre, the Sasebo Tomo no kai received a certificate of appreciation from the government.[xxvi]

The role of the Tomo no kai has two implications: first, the relationship between the government and Tomo no kai seemed rather vertical, with Tomo no kai basically cooperating with state direction. Second, the members seem to have paid little attention to diversity among victims and their agency.

Tomo no kai’s limitations were shaped by the state’s intervention in citizens’ sexuality during the war, which divided Japanese women into two categories: faithful wives/mothers on the home front who were protected by men’s military activity and women who were sexually available to soldiers.[xxvii] This gendered categorisation of women can be found in many parts of the world across histories, because women are often constructed as the ‘cultural symbols of the collective society, of its boundaries, as carriers of the collective “honour”’.[xxviii]

Repatriated women from Manchuria were not categorised as proper women but deemed sexually deviant.[xxix] The distinction was clear in the official documents of the repatriation project, which described them as ‘special ladies [tokushu fujin]’ as opposed to ‘general ladies [ippan fujin]’.[xxx] The main function of the medical care, then, can be understood as correcting ‘deviant’ women to make them ‘proper’ Japanese women by getting rid of the contamination attached to their bodies.

As mentioned above, the members of Tomo no kai were mainly from middle-class backgrounds, being proud wives and mothers who worked hard to contribute to the state during the war. The imperial gender ideology dividing women into ‘proper’ and ‘deviant’ was likely inscribed on Tomo no kai members, and the ‘correction’ could be justified and go uncriticised as a way of helping repatriated women. The Sasebo regional repatriation centre was closed in May 1950. Tomo no kai members did not talk about their activity at all until 1975.[xxxi]

Post-war collective silence

In the post-war period, the most striking characteristic of the issue of repatriated women from Manchuria has been the silence[xxxii] of the government, civil society, broader Japanese society, and among the victimised women themselves. Despite some sporadic media coverage of the issue since the late 1970s, there has been no political discussion and/or investigation by the government nor any recognisable civil action on the women’s behalf.

As the government has not taken responsibility for endangering women in Manchuria through its migration and war-related policies,[xxxiii] it has not openly acknowledged the women’s victimisation yet. At the same time, the state has persisted in ideologically distinguishing between ‘proper’ and sexually ‘deviant’ women.[xxxiv]

Although at various points Japanese feminist movements, particularly in the 1970s, tried to deconstruct the state-led segregation of women, later generations of feminists have not taken up the mission.[xxxv] In this sense, Japanese feminists and women’s groups in general have a history of alignment with the state’s propensity to divide women into those two categories. This structured maintenance of the specific gender ideology in Japanese society has deepened the silence around women repatriated from Manchuria, even if there have been a few recent cases in which the silence was broken.[xxxvi]

In order to analyse the silence surrounding the issue of sexual violence against Japanese women repatriated from Manchuria, referring to existing studies on different types of war-time sexual violence against Japanese women is useful. Researching socio-historically constructed invisibility of Japanese victims of the so-called ‘comfort women’ system of the Japanese military, sociologist Kinoshita Naoko explains that their victimisation has tended to be overlooked because they were ‘victims from a perpetrating nation’.[xxxvii] She argues that Japanese civil society groups, researchers, feminists, and politicians have placed excessive emphasis on the ethnicised and nationalistic aspects of the issue.[xxxviii] As a result, the dominant discourse has depicted Japanese as a homogenised group of the colonising power.[xxxix]

Furthermore, some Japanese feminist historians have criticised feminists in Japan[xl] for complicating issues around both Japanese and non-Japanese victims of wartime sexual violence under Japan’s militarism and imperialism, due to their failure to dismantle the state-led gender ideology. Japanese feminists, these historians say, must undertake a ‘critical self-reflection’[xli] on the history of Japan’s feminist movements.

Post-war Japan as a democratic nation?

Imperial Japan (1868—1947) was a military nation with a strong authoritarian tradition before it implemented the revised Constitution in 1947, which was drafted by the SCAP. The three basic principles of this post-war Constitution are renouncing war, upholding popular sovereignty, and human rights. This Constitution has thus sometimes been described as the ‘Constitution of Peace’.[xlii] In the post Second World War era, Japan has presented itself as a nation striving for public good and peace.

The recent political direction taken by the government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, however, aims to increase the state’s interference in the private matters of citizens, such as family relationships.[xliii] It also seeks to strengthen the power of Japan’s Self Defence Force by revising the post-war Constitution.[xliv] Japan can now be considered to be under scrutiny as one of the nations that have been backsliding to authoritarianism.

In recent studies, indicators of democracy have been described not only in relation to voting systems but also with regard to practices towards democratic ideals. For example, examining post-war Japan, political scientist Chiba Shin lists ‘dialogue, discussion, participation […] self-reflection, pluralism […] and accountability’[xlv] as crucial practices underpinning democracy. Based on this understanding, political scientist Okano Yayo argues that Japan has not yet been democratised, considering the government’s failure to demonstrate these democratic practices in responding to demands from the victims of sexual violence under Japan’s military occupation and colonisation in the Asian region. According to Okano, ‘continuous critical examination of how “we” are [and what “we” do]’[xlvi] is indispensable in practicing democracy.

This kind of rigorous democratic practice has also been missing in Japan’s civil society, at least in relation to issues of wartime sexual violence against Japanese women including those repatriated from Manchuria. The ‘absence of democracy in Japanese society’[xlvii] has been conjointly kept by the state and its citizens.

To end the collective silence surrounding these victims, it is crucial for the state and civil society to properly understand the diversities among victims of wartime sexual violence and engage in critical self-reflection. Moving towards capturing the complex nature of the issue of sexual victimisation of women under Japan’s imperialism can be an important first step for Japan’s fuller democratisation, after more than 70 years since the nation’s beginning as a democratic state.

Main image caption: Cenotaph located next to the pier of Maizuru port, one of the points of repatriation, built for those who faced tragedy in Siberia and Manchuria April 1999. Image credit: Mayuko Itoh.

Footnotes

[i] Inomata, Y. (2018) “Kataridashita Seibōryoku higaisya: manshū hikiagesha no giseisha gensetsu o yomitoku [breaking silence by victims of sexual violence: deciphering discourse of victimization of repatriates from Manchuria]”, in Ueno, C., Araragi, S., and Hirai, K. (eds.) Towards a Comparative History of Sexual Violence and War, Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 171–198.

[ii] Yamamoto, M. (2015) “Senji seibōryoku no saiseijika nimukete: ‘hikiage josei’ no seibōryoku higai o tegakari ni [towards re-politicisation of wartime sexual violence: sexual victimization of repatriate women as a clue]”, in Joseigaku: nihonjoseigakkai gakkaishi 22: 44–62.

[iii] Ministry of Health and Welfare (1997) Engo 50 nen shi [50 years history of support], Tokyo: Gyosei, 28.

[iv] Hikiage kō Hakata o kangaeru tsudoi (2017) Arekara 70 nen: hikiage kō Hakata o kangaeru [70 years passed: thinking about Hakata repatriation port], Hakata: Kyushu akaibusu: 50.

[v] Park, Y. (2016) Hikiage bungakuron josetsu: arata na posutokoroniaru e [introduction for repatriate literature theory: towards the new post-colonial], Kyoto: Jinbun Shoin, 16.

[vi] Yamamoto, “Senji seibōryoku no saiseijika nimukete”, 44–45.

[vii] For example, Inomata, “Kataridashita Seibōryoku higaisya”; Nagoshini, A. (2001) Daitōa sensō to hisenryō jidai [the great East Asian war and the occupation period], Tokyo:Tentensha: 90–91.

[viii] Nagoshini, Daitōa sensō to hisenryō jidai, 100; 73–4.

[ix] Ministry of Health and Welfare, Engo 50 nen shi, 38.

[x] Kyu Maizuru Hikiage Engokyoku (1961) Hikiage engo shi [the history of supporting repatriation], Ministry of Health and Welfare, 252–4.

[xi] Ibid., 252.

[xii] The Ministry of Labor and Welfare (1946) The Outline of Operating Medical Aid for Female Repatriates, archived at Uragashira Hikiage Kinen Shiryōkan.

[xiii] The Penal Code (1907) Act No. 45 of April 24, Article 212–216. Exemptions were made on eugenic grounds by the National Eugenic Act implemented in 1940. Other exemptions were introduced in 1948 through the Eugenic Protection Law, which was revised and reimplemented as the Maternal Health Act in 1996.

[xiv] Iwasaki, T. (1987) “Kuni ga meijita chūzetsu shujutsu [the state-ordered abortion operation]”, in Nikkei Medical (August): 216.

[xv] Fujikawa, N. (2003) “Pedagogy between Racism and Negation of Different Cultures: On the Pedagogy of Masatarō Sawayanagi”, in Forum on Modern Education 12: 98; 97–108.

[xvi] Ozeki, T. (2015) Rationalization of Life and Modernization of Home, Toyko: Keisō Shobō, 134.

[xvii] Ibid., 1.

[xviii] Garon, S. (1997) Molding Japanese Minds: The State in Everyday Life, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 132–3.

[xix] Ozeki, Rationalization of Life and Modernization of Home, 119–132.

[xx] Ibid., 135.

[xxi] Nishimura, F. (2000) “Hikiage engo to Sasebo Tomo no kai [Supporting repatriation and Sasebo Tomo no kai]”, in Zenkoku Tomo no kai (eds.) Zenkoku Tomo no kai 70 nen no ayumi: Kaiin ga tuzuru sōritsu kara genzai made, Tokyo: Zenkoku Tomo no kai Chūōbu, 228–232; 229.

[xxii] Kamitsubo, T. (1979; 1993) Mizuko no uta: dokyumento hikiagekoji to onna tachi [the song of unborn babies: documentation of repatriate orphans and women], Tokyo: Shakai Shisosha, 233.

[xxiii] In a fictionalised document based on interviews with medical staff at a repatriation office, there was an episode of a repatriated woman who was determined to give birth to her child. See Takeda, S. (1985) Chinmoku no 40 nen: hikiage josei kyōsei chūzetsu no kiroku [40 years of silence: the records of forced abortion on repatriate women], Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha, 86-100.

[xxiv] Fukushi Fusa (1947) The Report on Daily Life Guidance, archived at Jiyū Gakuen.

[xxv] Kamitsubo, Mizuko no uta, 225.

[xxvi] Ozeki, Rationalization of Life and Modernization of Home, 135.

[xxvii] Mackie, V. and Tanji, M. (2015) “Militarised sexualities in East Asia”, in McLelland, M. and Mackie, V. (eds.) Routledge Handbook of Sexuality Studies in East Asia, London and New York: Routledge, 60-63.

[xxviii] Yuval-Davis, N. (1997) Gender and Nation, London: Sage, 67.

[xxix] Watt, When empire comes home, 123–4.

[xxx] Kyū Maizuru Hikiage Engokyoku, Hikiage engo shi, 253.

[xxxi] Satake, Y. (2011) “Sasebo Tomo no kai and women’s protection”, in Christian Social Welfare Science 44: 72–77, 76.

[xxxii] Watt, When empire comes home, 125; also Park, Hikiage bungakuron josetsu, 10–11 for repatriates as a whole.

[xxxiii] Ibid., 71; 122.

[xxxiv] Chimoto, H. (1998) “Rōdō to shiteno baishun to kindaikazoku no yukue [prostitution as labor and modern family]”, in Tazaki, H. (ed.) Kau karada/Uru karada, Tokyo: Seikyu Sha, 141–194; 163–170.

[xxxv] Kano, M. (2018) ‘Jūgoshi’ o aruku [cruising the ‘history of after the war’], Tokyo: Impakuto Shuppankai, 314-7.

[xxxvi] Inomata, “Kataridashita Seibōryoku higaisya”,180.

[xxxvii] Kinoshita, ‘Ianfu’ mondai no gensetsu kūkan, 2–3; 3.

[xxxviii] Ibid., 242–3.

[xxxix] Ibid., 240; 243–4.

[xl] Fujime, Y. (2001) “Joseishi kenkyū to seibōryoku paradaimu [women’s history research and the paradigm of sexual violence]”, in Ōgoshi, A. et al. (eds.) Feminizumu teki tenkai [feminism-like revolving], Tokyo: Hakutakusha, 197–235, 208–212; Kano, ‘Jūgoshi’ o aruku, 324.

[xli] Fujime, “Joseishi kenkyū to seibōryoku paradaimu”, 211.

[xlii] Hashimoto, A. (2017) Nihon no nagai sengo: haisen no kioku, torauma wa dou kataritugarete iruka [the long defeat: cultural trauma, memory, and identity in Japan], Yamaoka, Y. (Trans.), Tokyo: Misuzu Shobō, 167.

[xliii] Honda, Y. and Ito, K. (2017) Kokka ga naze kazoku ni kanshō surunoka [why the state interferes in the family: behind the proposed legislations and policies], Tokyo: Seikyūsha.

[xliv] Hashimoto, 174–5.

[xlv] Chiba, S. (2009) ‘Mikan no kakumei’ to shiteno heiwa kenpō: rikken shisō shugi kara kangaeru [the peace constitution as an unfinished revolution: thinking from the standpoint of constitutionalism], Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. 67.

[xlvi] Okano, Y. (2011) “The issue of ‘comfort women’ and democratization in Japan”, in Ritsumeikan Gengo Bunka Kenkyū 23 (2): 247–259: 254.

[xlvii] Ibid., 257.