Deeper understanding of the planetary crises of our time requires the insights from the arts and Humanities and Social Sciences. The creative, critical and imaginative skills of literary authors and visual and other artists are crucial to overcome some of the epistemological, political, commercial, and technological barriers to journalism, academia and policymaking. These creative agents have the capacity to trigger both the thoughts and senses of a variety of audiences through engaging aesthetics and narrative strategies, presenting a diversity of voices and wisdoms, and exploring alternative forms and platforms of story production, circulation and consumption.

This is not to ignore the environmental impact of parts of the creative industry—consider the carbon footprint of prestigious biennales—or the contradictions between the green messaging in art and the embeddedness or complicity of some of its creators in environmentally unfriendly political, commercial or technological networks and structures. It is not an easy task either: it requires the practical skills of groups and individuals with outstanding creative talent and training as well as their ability to critically and imaginatively renegotiate popular, political, journalistic, academic and creative histories, institutions, languages, genres and styles. Moreover, it can be a risky task: in many parts of the world, the creative, journalistic and academic works addressing politically contentious topics such as the actors behind environmental destruction are prone to censorship or banning, while their creators and personal and professional circles may face psychological or physical intimidation, detention, or worse.

On the one hand, in the era of abundant, fast and never-ceasing flows of media and imagery, textual and audio-visual forms of representation can lose some of their capacity to move, connect and prompt action. In the context of platform and other forms of political and capitalist surveillance, visibility can even turn into ecologically and socio-culturally damaging forms of hyper-visibility. This also justifies calls for ‘the right to invisibility’, particularly for groups that have been subject to histories of marginalisation and power abuse. On the other hand, to combat visual or Anthropocene fatigue caused by the short-hype and spectacle-driven media industry, the innovative and imaginative skills of literary authors, visual artists and Indigenous communities remain crucial for ‘de-anaestheticising’ the public, refreshing stale or stereotypical visual and textual discourses, and keeping the environmental discussions and campaigns going.

Media and genre conventions and varieties

Creative media and genres each have their own strengths and limitations in capturing geological phenomena. For instance, epics are suitable for connecting different ages and human and other-worlds, while science fiction and fantasy, including cli-fi (climate fiction), explore human and technological transformations and adaptions to environmental changes in the far future. The novel, on the other hand, seeks to engage readers primarily by presenting its own, spatially and temporally delimited settings for storytelling. At the same time, the novel has the potential to make environmental threats and challenges relatable as urgent, contemporary issues that are deeply ingrained in individuals’ everyday lives. While represented as fictional settings and characters, the described conditions, events, feelings, thoughts and character developments seem real and happening in the here-and-now rather than in the worlds of legend or phantasy.

Professor of English and author Elizabeth DeLoughrey points to allegory as a central representational bridge between the past, present and future, and between external realities and ‘hyperobjects’—a more-than-human event or object in time and space, such as the planet and Nature, and human forms of storytelling. I argue that allegory goes beyond the use of symbolism and rhetorical tropes for aesthetic pleasure. Unavoidably shaped and limited by human languages and perspectives, allegory such as ‘the island’ can bridge metaphor and ontology by providing a space for the presence and agency of other-than-human beings. In creative work, these other-type ontologies, including ‘ghosts’ or ‘spirits’, themselves often function as next-level allegories for macro-issues, such as global pollution and climate change. Moreover, by triggering the senses and thoughts of their recipients, they can embody a performative call for practical forms of environmental and climate action.

In addition to the potential of and limits to narrative genres such as the novel and written and spoken language more generally, there has been an increase in prominence and effectivity of contemporary visual forms of expression and communication in representing hyperobjects. I argue that this is not only a matter of the relative opacity of language versus the relative transparency of visuality. In fact, it is a matter of presentation rather than representation. The media, technologies, cultural conventions, platforms and institutions around visuality offer possibilities for the presentation of visual work such as painting, installation, performance, or digital video in the public realm, with possibilities for audience participation and co-creation that are normally limited in the more private and individual worlds of novel and other forms of writing. The visual arts can be truly contemporaneous—that is: in, about, and with the worlds of the artists and their audiences—compared with the generally more secluded and autonomous, modern worlds of literary authors and their writings.

It is crucial to acknowledge here much longer histories of Indigenous storytelling, including forms of creativity that are contextual, involve audience participation, blur the distinctions between tradition and contemporaneity, incorporate both visual and oral elements, and interconnect human and more-than-human worlds. Indigenous authors and artists worldwide combine old and new oral, written and visual media, styles and technologies to present their previously marginalised or suppressed stories and wisdoms to the world.

Southeast Asia as creative-critical method

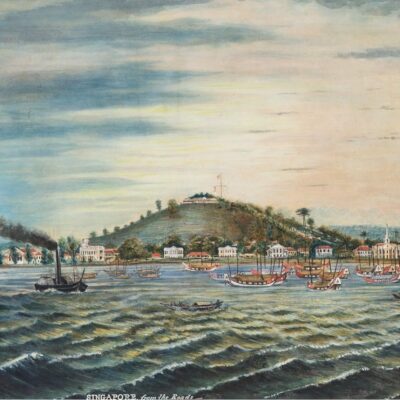

DeLoughrey refers to the common figure of ‘the island’ in literature and other creative forms as a particularly apt allegory for planet Earth, climate change and the Anthropocene. Islands are simultaneously bounded and permeable contact zones between the land and the sea, and humans and more-than humans, with some of the most complex, rich and threatened ecologies and related Indigenous knowledge and storytelling traditions on earth. Moreover, they demonstrate the inextricable links between human activity, social injustice, and environmental destruction, due to their long histories of colonialism, tourism, migration, slavery, war, authoritarianism, extractivism, monoculture plantations, nuclear testing, and waste dumping.

The effects of climate change, including rising temperatures and sea levels, are most clearly felt and visible in islands and archipelagos in Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean, and the Pacific. While each unique in their socio-political and cultural histories and natural conditions, they all present allegorical models to grasp the seemingly abstract and incomprehensible dimensions of more-than-human hyperobjects, and to imagine pathways to political change and environmental sustainability.

In Southeast Asia, archipelagic ‘liminal spaces’ between land and water, such as mangrove forests, marshlands, wetlands, and tidal zones, have shaped Malay and other ‘semiotic lifeworlds’. Scholars Agnes S.K. Yeow and Wai Liang Tham argue that allegory in Malay oral traditions, literature and other creative forms present ‘a methodology of reading where nature and culture co-evolve and co-develop via the mutual reading and interpretation of signs—through which various discourses are re-read, interrogated and critiqued’. Similarly, the authors in this edition of Melbourne Asia Review, approach Southeast Asia as a creative and critical method into the environmental humanities rather than merely a geographic or administrative site.

In various traditional and contemporary cultural expressions from the region, metaphor eliminates rather than reinforces the boundaries between fiction or symbolism and the real world, and interrelates different ontologies, including self and place, and culture and nature. For instance, alam in Malay, Malaysian and Indonesian refers simultaneously to nature and world or universe, and to the agency, communicative power, and interconnections of both their human and more-than-human constituents. Semangat means ‘spirit’, but also connotes a vital force or soul shared by humans and nature in the realm of alam.

Malay literary genres such as pantun poetry and Indigenous beliefs, rituals and storytelling, including mantera (invocations), bridge the human and more-than-human realms. However, both colonial and post-Independence power structures and rhetorics have fractured such ‘ecological ties between communities as well as with their terrestrial and littoral environments’ . This includes political interests and boundaries overwriting the natural land (tanah) and water (air) conjunctions between neighbouring states such as the Philippines and Sabah with the abstract, nationalist notion of tanah air. Commonly translated as ‘homeland’, the latter separates not only nations from each other, but also humans and nature.

In The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis, literary author Amitav Ghosh argues the Linnean system—the abstract, binomial nomenclature for organisms developed by Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778)—has contributed to the perception and exploitation of nature as a mere resource. In Ghosh’s view, the Linnean name ‘Mystica fragrans Houtt’ for nutmeg turns the seed into an isolated object without any agency or interconnection with the world around it. The very materiality of the nutmeg and its fruit, however, suggests multiple layers, textures, shapes, colours, and smells that embody and trigger connections, memories and actions.

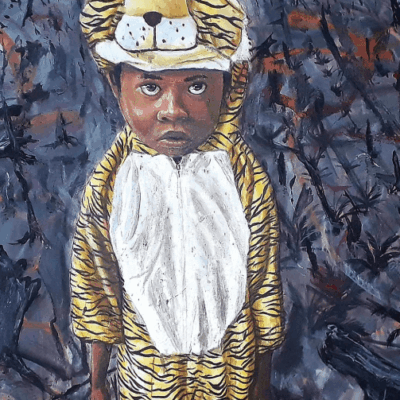

The everyday references in Malay/Indonesian (pala), Bengali (jâyaphal) and even Dutch (nootmuskaat), do not foreclose possibilities to see the nutmeg as ‘a tiny planet, or as a maker of history, or as something that hides within itself a vitality that endows it with the power to bless or curse’. The people of the Banda archipelago, home to the nutmeg tree and starting point of the Dutch spice trade, still sing songs about the nutmeg that are closely interlinked with memories of their ancestors and connections with their land. In his own fictional work, Ghosh attempts to gives voice and agency to the elements of nature, and the stories and wisdom of people interacting with them, such as the tides, mangrove forests, tigers and crocodiles of the Sundarbans in his 2004 novel The Hungry Tide.

Other contemporary storytellers also employ a biosemiotic lens as ‘a corrective to alienating discourses of essentialism, purity and authenticity’. This includes Malaysian poet Muhammad Haji Salleh (b. 1942) as well as visual artists such as Setu Legi (the creative pseudonym used by Hestu Nugroho, b. 1971). In 2015, Legi had an exhibition titled ‘Tanah Air’ in the Indonesian city of Yogyakarta, in which a variety of multi-media works referred to the environmental conditions, nationalist politics, business strategies, and social and cultural practices and wisdom behind both the literal (‘land-water’) and symbolic (‘Homeland’ or ‘Father/Motherland’) meaning of tanah air.

Moreover, local artists and communities, including Indigenous groups, increasingly use popular media such as film, comics and social media to engage younger audiences and establish global connections. The comic Dead Balagtas Tomo I: Mga Sayaw ng Dagat at Lupa (Dances of the Sea and Land, 2019) by Philippine comic artist Emiliana Kampilan tells the story of the formation of the Philippine archipelago ‘from its cosmic genesis to its modern national assemblage’, including forms of ‘trans-corporeality’, contact zones between human bodies and more-than-human nature, and queer histories. Anthropocentric, colonial and male perspectives are also challenged by the Palangka Raya-based youth collective Ranu Welum (est. 2016), which shares its environmental activism and explorations of Dayak indigeneity with the outside world through the documentary When Women Fight, parts 1 (2016) and 2 (2019) and other films and media. To this list, we can add the large variety of other border-crossing environmental art, film, literature, photography, design, and curatorial practices analysed in this special edition of Melbourne Asia Review.

Image: Person holding nutmeg. Photo by Na Hur/Pexels.