The domestic maritime connectivity of the micro-states of the Pacific islands is a unique and largely overlooked dimension of shipping supply chains. Pacific island states have long represented an anomality in global supply chains, despite occupying the oceans separating the modern strategic competition of west and east.

The problems are vast

The Pacific islands are home to the world’s smallest and most vulnerable populations by any metric. They are micro-economies with extremely limited global trading opportunities, or none at all, scattered at the very end of the world’s longest, thinnest and most expensive supply chains serving states of between 1,800 and 800,000 people (except for Papua New Guinea which has a much larger population). Their trading and connectivity realities are completely juxtaposed to most other Indo-Asian-Pacific ocean rim States, and yet post-WWII these Small Island Developing States (SIDS) have ended up tacked on to other, larger polity and economic boundaries: under ‘Oceania’ with Australia and New Zealand for the purposes of the United Nations, as part of ‘Asia-Pacific’ for development agendas such as the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, the Asia Development Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank; and now included in the newly demarked ‘Indo-Pacific’ boundary set by the US and its allies to curtail their perceived threat of a modern China’s expansion.

The simple reality is that for decades the unique and increasingly chronic connectivity issues facing Pacific states has simply not been visible, largely ignored and unattended—the issue a minimal footnote at best in the priorities of bigger (and usually continental) States. For Pacific maritime island, atoll and archipelagic nations, domestic shipping is an essential service, enabling not only the countries’ fragile economies but their entire societal network. For most of the Pacific, such domestic connectivity is usually aged, inadequate, inappropriate, unaffordable and often unsafe with its often colonial-era infrastructure under constant assault from cyclones, tsunami, storm surges, sea level rise and flooding.

The COVID-19 pandemic proved beyond any doubt that shipping is the absolute lifeline of Pacific small island states. Life without airline connectivity was hard but went on without the tourists on which the economies of many depend. But survival is not possible without shipping for societies now completely dependent on imports of all fuel, most food and virtually every other essential commodity. Once the world’s greatest navigators and seafarers, colonising the greatest ocean under sail a millennia before either Leif Erikson or Columbus ‘discovered’ America, the Pacific is now entirely dependent for transport security on externally owned and operated international liners, often island-hopping from rim ports in the US, Asia, New Zealand and Australia, connecting remote marginal sub-regional hubs with spindly, fragile spokes.

Such international service is generally considered adequate, if the most expensive in the world. It doesn’t make sense for operators like Swire, Matson’s and Pacific Direct to run old or inefficient ships on such remote feeder services and lack of competition means consumers have no choice but to pay the prices demanded. But the domestic service providing essential last mile connectivity within each state is substandard and in crisis, often in extremely poor repair with a vicious cycle of old ships replaced by old. ‘Last-mile’ in a Pacific sense can mean blue-water passages of hundreds of sea miles to connect outer-island communities of only a few hundred people in some of the poorest countries in the world. Routes in Fiji, for just one example, include providing essential connectivity to the 1,500 people of Rotuma to the north, a return voyage of more than 650 nautical miles, or the southern route to the 500 strong community on Ono-i-Lau, over 500 nautical miles return. Such services are not economically viable and the cost falls to already overly indebted state treasuries to either provide directly or subside an inadequate private service.

There are two additional major barriers to add to this already grim scenario:

- The Pacific is already the most dependent region on imported fossil fuels at the highest prices and is likely the hardest region to transition to any alternative energy source given the cost of transporting and refueling of any known alternative. If the Pacific can barely afford its current diesel dependency where fuel is still often dispensed in 200-litre drums, sometimes rolled by hand across a reef, how will it ever afford the refueling infrastructure for any electro-fuel of the future?

- These oceanic States, already the most vulnerable in the world to natural disasters, are now situated as the first collateral damage in a deepening global crisis not of their making and beyond their fiscal capacity to respond or adapt. In a region where a single event can decimate large proportions of local fleets and infrastructure, the years ahead spell only compounding risk for economies that are already amongst the most debt laden and dependent in the world. For the Pacific, the threats to water, food and physical security from climate change are much more real and present than those posed by the short-term war-gaming and economic empire building of great state alliances that ring their great Ocean home. If providing essential maritime connectivity to its citizens is stretching current capabilities, this situation will only worsen as we race past 1.5 degrees of global warming.

Possible solutions

One small bright spot in a fast-darkening horizon is the potential to build local resilience by re-fleeting the domestic fleet currently providing last-mile supply with green, affordable and appropriate replacements using the climate financing unlocked by a universal mandatory price on intentional shipping emissions.

Since 2015, an alliance of Pacific states that have been pressing for the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) to adopt a high ambition approach to shipping decarbonisation have proved catalytic to greatly increasing the levels of ambition for this ‘hard-to-abate-sector’ to full decarbonisation around 2050, including the introduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) pricing and a commitment to contributing to an equitable transition that leaves no State behind. Persistent Pacific diplomacy has prevailed at the IMO as shown by the current commitment to a complete decarbonisation agenda for international shipping in the space of a generation.

In what is being termed a ‘trillions transition opportunity’, IMO is committed to implementing economic and technical measures to achieve this ambition by 2027, with member states negotiating a price in shipping GHG emissions from proposals ranging from a low price of USD 20/ton/CO2 equivalent to the most ambitious call for a universal flatline GHG levy with an entry price of USD 150/ton/CO2-equivalent that would generate upwards of USD 100 billion in annual revenues into a dedicated IMO fund. The revised IMO Strategy sets three primary objectives that the use of these revenues will need to achieve; promoting the energy transition, incentivising the fleet and contributing to a level playing field and a just and equitable transition. Negotiations continue at IMO over what share of revenues this will unlock for the Global South, and particularly the States most vulnerable to climate change. There appears strong consensus at IMO that the particular needs of Small Island Developing States and Least Developed Countries must be prioritised. In theory, there must now be strong potential to find sustainable long-term solutions to the Pacific’s connectivity issues.

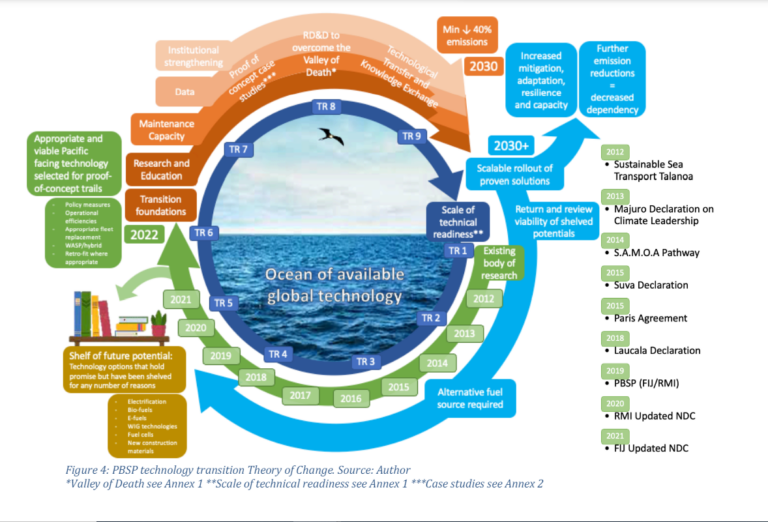

But achieving a paradigm shift in relation to decarbonisation at Pacific domestic scale is not simply a case of scaling-down proven international trends. The unique geography and economies of Pacific maritime States require a bespoke solution. The alliance of high ambition Pacific states is attempting to design exactly that with the Pacific Blue Shipping Partnership (PBSP). The PBSP is a call for an initial USD 500million investment spread over a group of countries to allow a coordinated program of change to be built. The alliance is co-chaired by Fiji and the Republic of the Marshall Islands, who have already committed to complete maritime decarbonisation by 2050 in their Nationally Determined Contributions (a climate action plan) under the Paris Agreement on climate change.

The PBSP recognises that a complete revolution is needed in technology and fleet management and operations, as well as financial investment and program delivery away from existing structures. The Pacific’s minute size and high commercial risk means that there are no economies of scale to allow any access to maritime investment finance and insurance. Full regional decarbonisation of shipping at the scale required is thought to require an investment of more than USD 10 billion into this sector and will ultimately need to be accompanied by a shift to as-yet-unknown future fuels. This transition is beyond any national capacity to resource. Regional programming in this past decade has proved inadequate for catalysing any paradigm shift of scale or speed required.

The blue-water ships servicing much of the Pacific’s domestic routes are small by international scale (under 5,000 gross ton, most less than a 1,000 ton). But this scale, combined with the plentiful wind power in many Pacific countries, allows for innovative new designs for wind-assisted ship propulsion capable of achieving up to 80 percent improved efficiency with known technologies. An example is Ae Juren, the 48 metre Marshall Islands Shipping Corporation general service vessel being commissioned currently in a small yard in South Korea. This vessel is the result of German development funding and academic collaboration with local researchers and demonstrates proof of concept of the fuel efficiency achievable at Pacific scale using wind, innovative hull design and ancillary systems.

Locally-led research has identified a range of available technologies that can be harnessed to meet the Pacific’s ambitious targets. New vessels and well maintained, regularly serviced ones, will always be more efficient than old ships. Yet the maintenance facilities and ship slipways of the Pacific, essential for the ongoing repair, upkeep and operation of the fleet, are in woeful repair, where they exist at all. Flettner rotors are obvious candidates for a large percentage of the international and local tanker and bulk cargo fleets, with modern design retrofits offering around 20 percent saving potential and newbuild designs considerably more. Re-invigorating traditional sailing knowledge is key to revitalising small sail hybrids for local village use. Technologies like Wing-in-Ground craft are potential game changers.

There is an ocean of technological opportunity. The challenge for the Pacific Island nations is to plan what will work at Pacific scale and then convince the global climate financing community that this is a priority that must be viewed through a Pacific lens to develop a Pacific-centric solution. The innovative use of blended and no-regrets climate financing modalities (including access to the Green Climate Fund, IMO’s greenhouse gas emissions levy revenues, bilateral assistance from development partners, etc) presents as the only option for breaking the current lack of investment capacity available for the Pacific’s domestic transition. A durable and sustainable solution requires a shift to a high initial capital expenditure, medium operational and low fuel cost, fully insured model. This requires the politically difficult issue of agreement on the international funding necessary, but it is essential for providing appropriate shipping solutions in these countries.

Figure 1. Pacific Blue Shipping Partnership Technology transition theory of Change.

Source: Micronesian Centre for Sustainable Transport PBSP Technology Working Group Working Paper #4 ‘PBSP governance, finance and technology narrative’, November 2022.

Does the Pacific have a choice other than attempting to decarbonise at speed and scale? Failure to undertake the transition now will see the same states increasingly disadvantaged by their ongoing diesel dependency. Advances in shipping design, technologies, fuels and operational practices is a fast-moving field and there is a widening technology inequity gap between the smallest small states and the global decarbonising economies. Globally, full decarbonisation of all sectors is the only available option to address the climate emergency. However, this transition, while essential, is beyond any national capacity of Pacific Small Island Developing States to resource or sustain in the foreseeable future and, in many instances, unlikely to result in overall positive commercial investment returns. Domestic shipping in a Pacific island context has always been a marginal economic enterprise at best, and this is unlikely to improve in the foreseeable future, even with an optimistic economic forecast. A fully cost-recoverable transition is not possible or realistic and the sector will require ongoing external assistance for the foreseeable future, most likely rising as the full effects of climate change manifest.

It should not be assumed that a transition to alternative technologies will result in a fully profitable domestic sector; after all, this has not been achievable in a century of cheap fuel. Therefore, at least a portion of the requisite investment must be made on a ‘no regrets’ basis and on the understanding that this is the initial step in a generational process. The costs of inaction are higher than taking action and will only increase with delay.

Peter Nuttall is the Scientific and Technical Advisor at the Micronesia Center for Sustainable Transport based in the Marshall Islands. Since 2013 Dr Nuttall has led the development of a multidisciplinary research and teaching programme to underpin transition to low carbon sea transport for Pacific Island countries. His recent work includes research design of a universal mandatory GHG levy for shipping. In a pre-academic life, Peter worked as a wooden boat builder, sailor and captain and has sailed much of the Pacific Ocean over 40 years. He lives with his captain and sons on a small wooden sailing ship that operates primarily on low carbon technologies and renewable energy.

Main image: Lautoka, Fiji. Credit: photobomb/Flickr

This article is part of the ‘Blue Security’ project led by La Trobe Asia, University of Western Australia Defence and Security Institute, Griffith Asia Institute, UNSW Canberra and the Asia-Pacific Development, Diplomacy and Defence Dialogue (AP4D). Views expressed are solely of its author/s and not representative of the Maritime Exchange, the Australian Government, or any collaboration partner country government.