Cultural collections transit the world for exhibition, crossing geographic borders and environments between cooler climatic zones and from tropical to temperate and back. Protecting the works being exhibited through climate control is a central concern for museums. An understanding of what climates are best suited for particular collections, their management, loan and repatriation are part of negotiations between loaning and borrowing museums. But these discussions usually represent particular versions of cultural preservation and overlook others. This can have negative implications for collections, and the historical narratives museums located in tropical Southeast Asia present.

The importance of temperature and relative humidity controls for touring exhibitions

Touring exhibitions that provide access to global collections require agreement on several matters before cultural exchanges go ahead. An important one is the agreed climate controls, where the borrower will agree to maintain certain temperatures and relative humidity levels in their exhibition spaces for the collections being loaned. If the parties cannot agree or provide the climate conditions being requested a touring exhibition may not go ahead.

From the Global North to the Global South

The difficulties in reaching agreement on climate control may explain the limited number of international touring exhibitions from the US and Europe that are hosted by Southeast Asian nations. The exception to this is Singapore, where a review of National Gallery of Singapore’s annual reports from 2016 to 2023 shows six loans from European or American museums. An equivalent number of touring exhibitions from the major European or American museums to other Southeast Asian nations is rare. Touring exhibitions are made possible by various factors, primarily economic and cultural resources, but the National Gallery of Singapore’s ability to comply with the specified environmental conditions outlined in loan agreements is very important. The Gallery has a 24-hour HVAC system (Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning) and maintains ‘acceptable’ museum environments which can be further adapted to meet exhibition loan requirements in separately zoned gallery spaces, such as the Singtel Special Exhibition Gallery.

The disparity between the loan rates of exhibitions from Europe and the US to Singapore compared to other nations in Southeast Asia can’t be solely attributable to the borrowing institutions’ climate control capabilities. But environmental factors play a significant role in loan negotiations. This means that access to the well-known global collections is more possible in Singapore than other Southeast Asian nations.

From the Global South to the Global North

With an increasing focus on the Global South, world migration and diaspora communities, there is a greater demand for collections loans and cultural exchanges from the Global South to the Global North. For example, the National Museum of the Philippines recently loaned Juan Luna’s 𝘜𝘯𝘢 𝘉𝘶𝘭𝘢𝘲𝘶𝘦ñ𝘢 to Dubai where it is now displayed alongside Auguste Renoir’s 𝘓𝘢 𝘛𝘢𝘴𝘴𝘦 𝘥𝘶 𝘊𝘩𝘰𝘤𝘰𝘭𝘢𝘵 and Edouard Manet’s 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘉𝘰𝘩𝘦𝘮𝘪𝘢𝘯—just recognition of Juan Luna’s artistic status and a form of validation for diaspora Filipinos residing in Dubai. Likewise the 2017-2018 EUROPALIA at Bozar, Belgium hosted Power and other things, an exhibition of Indonesian collections from the last 300 years.

The agreed environmental controls for these exhibitions are not publicly known or whether the climates provided meet the requested specifications of the collections being borrowed. In some cases the climates provided can exceed what an object has experienced in their lifetime which contributes to increased risks of mechanical damage. Conservator Margarita Villaneuva from the Lopez Museum in the Philippines draws attention to the this and shows how collections from the tropics are more often required to change and adapt to the narrow temperate climates of the borrowing museums. Villaneuva and others refers to this as ‘climate colonialism’, highlighting the unfair sharing of collection risks. Although the paper is one of the few published examples on the topic, such restrictive environmental standards dominate collections loans, and in practice tend to be non-negotiable for collections on exchange between the tropics and the Global North.

Museum operational processes in the Global North continue promote practices that exclude museums who do not fulfill the criteria

Southeast Asian nations are shouldering the greater portion of the risks and mechanical changes to their collections. To my knowledge, there are no museums in the Global North who offer a climate zoned gallery space for incoming collections from the tropics, like that offered by the National Gallery of Singapore. Whilst some risks can be managed with appropriate crating and packing techniques to allow for acclimatisation of collections, this situation underscores a disparity in museum practices which could have profound implications for the longevity of Southeast Asian collections when on loan.

Established international museum environmental guidelines

Museums in the Global North have historically prescribed environmental standards of 20 oC ± 2oC and 50% Relative Humidity ± 5%, which were adopted due to the understanding that these parameters were universally applicable. This ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach has led to confusion and difficulty for Southeast Asian museums as they try to meet these standardised expectations which have been costly, environmentally unsustainable and somewhat inaccurate for specific collections and local climate conditions.

Fortunately, assumptions about the best museum climates have been critically examined in recent decades. With a focus on sustainability and diversity within museums, many museums have adopted revised guidelines, drawn from new research and recognition of the real costs of tight environmental controls on museum budgets and effect on greenhouse gas emissions (although this discussion is ongoing). Two peak museum conservation organisations, the International Council for Museums-Committee for Conservation (ICOM-CC) and the International Institute for Conservation (IIC), have adopted the 2014 Environmental Guidelines ICOM CC and IIC Declaration. Several others also advocated for change, such as the Bizot Group—the international network of art museum directors from major institutions around the world. The Group endorsed the Bizot Green Protocols in 2014, and a refresh in 2023, and handbooks #1 and #2 for the adoption and touring of collections. In addition, the Australian Institute for Conservation of Cultural Materials (AICCM) guidelines, and a chapter of the 2023 handbook of the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning (ASHRAE) Engineers on ‘Museums, galleries, archives and libraries’ have adopted revised guidelines.

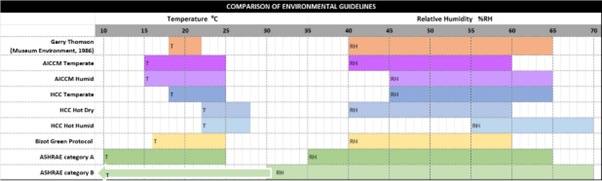

Figure 1: An overview of museum world standard environmental guidelines and their varying environmental commitments.

From the AICCM environmental guidelines. Used with permission from Amanda Pagliarino, Queensland Art Gallery.

Garry Thomson’s influential 1978 book The Museum Environment has informed museum climate guidelines for much of the 20th century, while the 2002 Heritage Collections Council of Australia established temperate, hot dry and humid recommendations in 2002, in acknowledgement of Australia’s diverse climatic landscape and recent conservation research. In 2018 the Australian Institute for Conservation of Cultural Materials followed suit by establishing temperate and humidity guidelines, illustrating more progressive controls than those internationally practiced and perhaps acknowledging Australia’s engagement with touring exhibitions from the region such as the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT) at the Queensland Art Gallery / Gallery of Modern Art. It was not until 2015 that the Bizot Green Protocol and the 2019 ASHRAE standards were released, which are now globally consulted, although, as already mentioned, narrow environmental standards still endure.

Some well-established museums have embraced the Bizot Green Protocols. Of the 16 museums, two are from the Asia Pacific region, the National Gallery of Singapore (NGS) and M+ in Hong Kong, while the others include the likes of the Guggenheim and MOMA from the US, the Tate in the UK, the Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands, and in Australia the National Gallery of Victoria and the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Together they have established a working group with 54 members, but museums still facing the challenges of hot, humid conditions are under-represented and the transition towards more flexible environmental guidelines has not been adopted worldwide. Further, conservation practice is still, in the main, informed by research undertaken in Europe and North America, and while useful and reliable references, these may not be directly applied to regions with different climates like in tropics.

The challenges of tropical climates

Museums in Southeast Asia manage collection care amid challenging climates. In this region, temperatures are often above 27oC and above 75% RH, with a greater variation in Bangkok and Manila compared to the more equatorial levels recorded in Kuala Lumpur and Singapore. It is not surprising that museum environments in these climates often exceed the parameters of the revised environmental guidelines presented in Figure 1 (above).

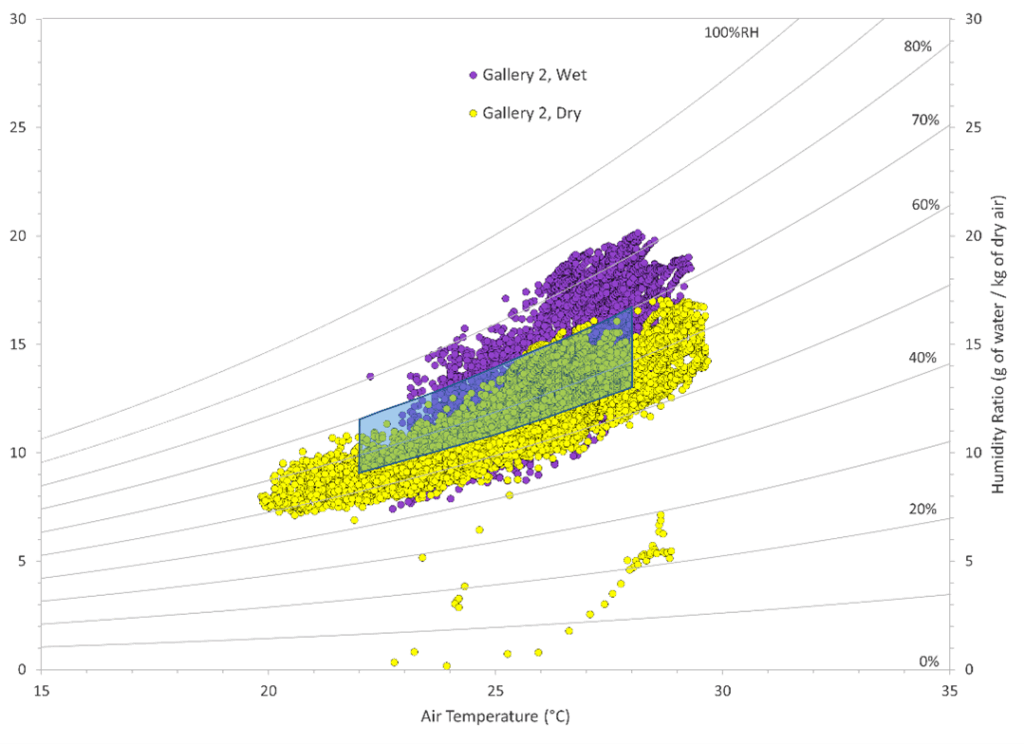

Figure 3 (below) shows temperature and relative humidity recorded in the National Museum of Fine Arts, the Philippines. The wet season is represented in purple and the dry season in yellow. The blue box shows the temperature and humidity range recommended by Australia’s Heritage Cultural Council (22-28oC and 55-70%RH). Evident is how often the gallery climate does not meet the HCC targets. It is most probable that exposure to the higher temperatures and relative humidity will have implications for thermal stability, mould, and the eventual life expectancy of the collections, and mechanical changes are evident.

Figure 2. Psychometric plot of the temperature and relative humidity in the National Museum of Fine Arts, the Philippines (Gallery 2) 6 December 2017 to 23 February 2019).

For further details see the publication by Calano and Tse, 2025. Used with permission from Calano and Tse.

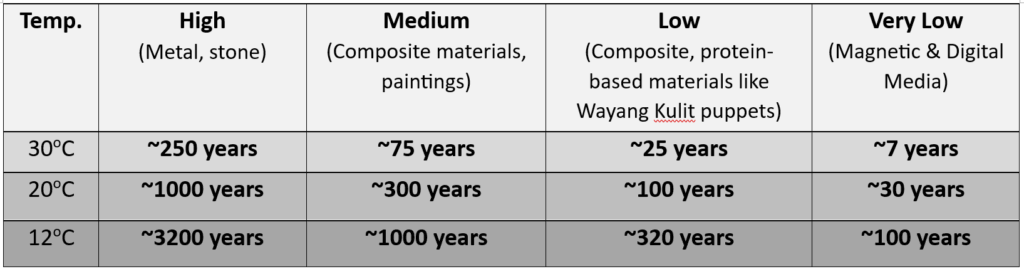

Figure 4 (below) illustrates the lifetimes of materials based on their category of stability and sensitivities. An item such as stone with high stability will last 250 years at 30 oC, and for 3,200 years at 12 oC. However, a Wayang Kulit puppet from Indonesia with low chemical stability, will last 320 years at 12 oC, and just 25 years at 30 oC. This is because material decay is inevitable, according to modern science, and the elevated temperatures and humidity levels characteristic of tropical Southeast Asia accelerate this process, potentially reducing the lifetimes of collections. A general rule for organic materials is that chemical decay is delayed by lower temperatures, and a 5oC drop will double the lifetime of collections.

Figure 4: Lifetimes of materials based on their category of chemical stability and sensitivity.

Adapted from the Canadian Conservation Institute’s Agents of deterioration.

Southeast Asian cultural practices and perspectives

Anthropologist Ghassan Hage observes that ‘Things decay in very different ways’, and importantly, ‘some processes of decay are welcome and some are resisted’.

For many Southeast Asian nations, this is evident through the way care and custodial practices have emerged in tropical climates through experiential knowledge and collective understanding. Traditional palm leaf manuscript monastery libraries in Thailand are a good example, often located above water to stop damage from termites and ceremoniously wrapped and placed in custom made boxes or cabinets to slow down moisture exchange and material movements. The same principles are being used for a newly built archive over a pool of water in Bangkok. Another example is the annual airing of Wayang Kulit puppets in Indonesia by custodians, placing them in the bright sun where UV light slows or destroys the growth of microbes. Modern science regards strong sunlight, UV light and water as elements to be excluded, but these Southeast Asian examples of care show how situated knowledge is been pragmatically employed.

Sociologist Boaventura de Souza Santos argues that these practices of care and other knowledge systems, which are sometimes ignored by modern museums and heritage organisations, ‘confronts the logic of the monoculture of scientific knowledge’. De Souza Santos also contends that social and cultural knowledge should not be seen as alternatives that discredit modern science, but together they form an ecology of knowledge: ‘It implies, rather, using it [scientific knowledge] in a broader context of dialogue with other knowledges.’

In cultural conservation, we can see how cultural care practices like the ones above are part of social and cultural eco-systems, but they also share traits with scientific knowledge such as resetting the ‘mould growth clock’ (as also reported in the Bizot Green Protocol) and the lifetimes of collections. In the geographic locations of Southeast Asia where high temperatures, high relative humidity and other environmental risks are greater, decay is accepted within people’s lifetimes.

Conclusion

I argue that a critical engagement with scientific knowledge and its interrogation in an ecology of knowledges, contexts, practices and communities in which it operates, are important attributes for cultural conservation to embrace. This also means extending dialogues on the expected lifetimes of collections in tropical Southeast Asia and how they should appear, and knowledge of collection behaviour in hot, humid climates drawn from shared experiences, observation and the unique materials from which collections are made. Ultimately this will better serve museums in the tropics to advocate and manage collection risks in Southeast Asia as cultural exchange widens. Yet there is still much to learn with few publications in this area.

Southeast Asia is stepping up to these challenges. In recent years, government heritage agencies and universities, are seeing the value of cultural conservation and investing in training, research and conservation programs of their own rather than studying abroad. For example, conservation training was established at the Institut Seni Indonesia (ISI) in 2023, and plans are underway to set up a program at the University of the Philippines, while several existing and new programs are available at Silpakorn University in Thailand. Such growing capacity and knowledge should bring about positive impacts.

Presently, two museums from the Asia Pacific have committed to the Bizot Green Protocols, and to my knowledge there are no published environmental guidelines specific to Southeast Asian nations such as those that exist for Australia. Perhaps this is because there are few professional conservation organisations, and those that do exist, such as Institut Konservasi in Indonesia, were established only recently. As conservation programs, research, professional organisations, government support and the need for conservation widens, representation in Working Groups like the Bizot Green Protocols, will bring about change. Co-currently the major museums from the Global North will learn from the research and skills being generated from the Southeast Asian region and may likewise rethink conservation ‘best practices’ and who benefits. This may bring about adaptive strategies and a fairer distribution of collections risks and climate guidelines for collection care worldwide.