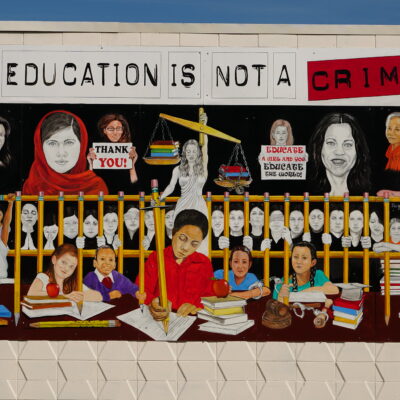

Discrimination, hatred, and acts of violence towards the religious Other is on the rise, according to a recent Pew report analysing ‘harassment’ of religious groups by governments or social actors. It’s not a good time to be a Christian in North Korea, a Shiʿi Muslim in Afghanistan, or a Falun Gong practitioner in China.

Many Muslim-majority countries do not fare well in the report, and the rise in religiously sourced violence and intolerance by certain governments and groups has raised questions about Islam’s stance on the rights of religious minorities. Many ask: Why does Islam appear to advocate distrust and conflict with people of other faiths? Others point to periods and places of generally peaceful coexistence as a precedent, suggesting intra- and inter-religious tension is an aberration.

Looking back at history, when Islam spread beyond the Arabian Peninsula in the seventh century CE, it encountered diverse religious communities. While many people did convert to Islam, others continued practicing their own religions. This period became a turning point in shaping how Islam, as both a spiritual tradition and a political force, interacted with other faiths and approached religious diversity.

Today, the Muslim world remains incredibly diverse, home to numerous religions and Islamic sects. Faiths such as Zoroastrianism, Ezidism, Judaism, and Christianity are considered indigenous to the regions that later came under Arab Muslim rule. Even within Islam itself, there are a wide range of interpretations and beliefs, at times deeply different from one another. Due to this internal diversity, it is not possible to speak of a single, monolithic, ‘true’ interpretation of Islam.

Although it is important to understand the formative period of Islam to see how Muslims interacted with non-Muslims, it is equally significant to examine how the foundation text of Islam—the Qur’an—serves as a guideline for such interactions. The way these relationships are described, along with their various interpretations, directly influences the rights granted to religious minorities in countries governed by Islamic groups.

Although for many, the Qur’an provides an ethical basis for good social relations, some Muslim groups justify their attacks on non-Muslims through appeal to scripture and their interpretation of Islamic religious law (the shariʿa). For this reason, we need to understand how the Qur’an is read as peace-promoting by most, but violence-promoting by some. Furthermore, if we wish to challenge the worldview of the latter, we require a conceptual framework rooted in Islam’s key text. This provides a legitimising methodology to understand religious tolerance and the acceptance of diversity, with a focus on the Qur’anically required behaviour of Muslims toward non-Muslims in contemporary society.

Clearly, any discussion of minority rights in Islam, or Muslim minorities’ rights in non-Muslim societies, is inherently linked to broader political issues. The question of religious tolerance and minorities’ rights is significant for two reasons. First, the rise of political Islam in the post-colonial era has contributed to the establishment of so-called Islamic states across various parts of the Muslim world. It is unreasonable to ignore the violence that has been perpetrated in the name of Islam, often targeting religious minorities. Second, as mentioned previously, it is important to recognise that the Muslim world (in majority and minority settings) is incredibly diverse, made up of many different religions, cultures, and ethnic and Indigenous groups. Because of this, it is vital to understand the political and sociological contexts that shape interrelations between Muslims and non-Muslims.

There are two important dimensions to consider in conceptualising Islam and minorities’ rights. The first is the historical: how did Muslims traditionally conceive of ordering their diverse societies? Across the pre-modern globe, most societies were stratified and hierarchical. The dominant caste shaped the contours of each society with their laws, rules, and customs. Pre-modern societies did not possess an understanding of freedom of religion enshrined in a system that instituted equality before the law supported by a commitment to individual human rights. For example, the first great Islamic empire, the Umayyads, instituted an ethno-religious patronage system in which Arabs ruled large swathes of non-Arab and non-Muslim territory, and non-Arab converts to Islam required an Arab Muslim patron. As historian Marshall G. S. Hodgson put it: ‘to be a Muslim in the full political sense, a convert had to become associated…with one or other of the Muslim Arab tribes.’ In contrast, the Mughal emperor Akbar the Great ruled over a military-dominated bureaucracy, one in which religion was no bar to ascendancy. This is all to say that pre-modern Islamic history is complicated and it is a gross simplification to say that Muslims built a world based on religious domination in which the non-Muslims in their midst were poorly treated subjugated subjects.

The second important dimension to consider is that the transition from the traditional to the modern has been a site of contest, often bloody. It reflects the ongoing battle for who gets to speak for or about Islam in the context of Muslim countries emerging from colonisation and establishing new nation-states with the boundaries of national identity often drawn along ethno-religious lines. Islam is invoked to support hierarchies of privilege whether intra- or inter-religious. Although most Muslim rulers and governments have had to at least tacitly acknowledge and establish Islam, in practice Muslim nations have tended to instrumentalise religion for political purposes, either to anathematise their enemies or to curry favor with powerful religious lobbies. This dynamic directly affects how non-Muslim minorities are treated and how interreligious relations are managed.

This dynamic is also at play for long-standing Muslim minorities in places such as China, India, the Philippines, Thailand and others. Here, state management of Muslims has often been coloured by a fear (justified or otherwise) of militancy. Over the course of the twentieth century, some ethnonationalist insurgencies mutated into religious ones, either due to ideological appeal or direct support from jihadist transnational organisations. Muslim citizens living as minorities, the majority of whom are not involved in militant activities, have been caught in the literal and metaphorical crossfire.

It is the need to understand these two dimensions that has resulted in the collection of articles in this edition of Melbourne Asia Review. We have chosen to focus particularly on countries and areas where the connection to Islamic history is long and well-established, rather than on ‘new world’ countries such as Australia, where Muslims are still in the process of settling and establishing themselves as part of the religious landscape. For heritage places, Muslims and non-Muslims have spent centuries living side-by-side, often successfully. Yet because religion deals with matters of life and death, it can also be a force for division as much as for spiritual edification.

Authors: Dr Rachel Woodlock and A/Prof. Muhammad Kamal.

Image: Interior of the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul. Credit: Yasir Gürbüz/Pexels.