Overseas remittances, the money sent home by migrant workers, are enormously important for developing nations’ economies and have a huge impact particularly in rural areas where they supplement families’ incomes and those of the wider community. They constitute perhaps the most significant form of ‘transnationalism from below’—the forging of transnational linkages between migrants and homelands by migrants themselves.

Remittances are particularly important in the case of the Philippines. More than US$430 billion (AU$585 billion) in remittances during the last 46 years have helped the Philippine economy promote investment, realise economic growth, and reduce poverty. Filipinos abroad have helped their home country’s economic growth through their fund transfers and transnational work. Remittances to the Philippines account for 40 percent of domestic consumption and can result in higher levels of educational attainment and household entrepreneurship, both of which can further increase local incomes.

Of course, international migration produces potential problems for families given the physical separation of family members. Some scholars have also suggested that overseas remittances may breed inequality in rural communities. Nevertheless, there is substantial evidence that remittances have a positive impact on rural livelihoods, particularly in situations where basic needs cannot be met without recourse to migration.

How can remittances have the most positive outcomes in rural areas, particularly in the Philippines? My research shows that multiple factors may have to be present: good local governance, facilitative business climate-related services, responsive financial institutions, and more financially literate rural residents.

It is not enough that we look at the outcomes of remittances in local communities, such as businesses created, properties purchased, and amounts consumed locally using earnings from abroad. Processes that occur within migrant families, in remittance owners’ relationships with financial institutions and entrepreneurs and with people and institutions in rural communities, all determine how well these remittances are, or are not, utilised locally.

Studying a locality’s remittance investment climate

I explored the outcomes and processes surrounding remittances and rural home town investing in two municipalities in the Philippines: San Nicolas municipality in Ilocos Norte province (northwestern Philippines) and Moncada municipality in Tarlac province (approximately 150 kilometres north of the capital Manila), for four months each: from September 2018 to June 2019.

I implemented a mixed methods tool called RICART (the Remittance Investment Climate Analysis in Rural Home Towns). This tool tries to determine if the household receiving remittances is financially literate and capable of making investments, and if the rural community’s investment climate is conducive for any type of investment. RICART can be implemented in any rural community whether it is proximate or distant from a nearby city.

I surveyed migrant and non-migrant households (the latter as a comparison group) who were recruited through quota and referral sampling. A total of 443 migrant and 463 non-migrant households were surveyed in all the villages (barangay in Filipino) of San Nicolas and Moncada. They were asked about their financial literacy and behaviors, their incomes and expenditures, and their activity relating to saving, investing and opening and running a business locally.

I also conducted numerous interviews with key informants and focus groups to determine the economic and investment conditions of San Nicolas (total N= 95) and Moncada (N=58). Some heads of migrant households surveyed also participated in object-centred interviews (OCIs [total N=59]), which involve methods other than verbal interviews to help respondents answer sensitive questions surrounding money and the family. I also collected a total of 162 sets of documents about San Nicolas and Moncada, on topics such as sources of local revenue, regulations for entrepreneurs, and local governance performance.

I implemented what is called a fully integrated mixed methods research design so that understanding of people-place interactions on remittances and rural home town investing covers both outcomes (quantitative methods) and processes (qualitative methods). The product of integrating quantitative and qualitative data is what RICART authors call the remittance investment climate (ReIC) of a rural locality. Joint display tables were used to make sense of survey results and of interview and documentary data.

Geography and levels of urbanisation affect the use of remittances

San Nicolas (2020 population: 38,895) in Ilocos Norte province is between Laoag and Batac cities. Moncada (2020 population: 62,819) is some 30 kilometres from the capital city of Tarlac province, Tarlac City. Data from the national government’s migration agencies in 2017 show that San Nicolas had more overseas migrants (7,938) than Moncada (4,653), despite is smaller population.

Approximately 21.6 percent and eight percent of San Nicolas’ and Moncada’s populations respectively work and reside abroad. More than 5,000 permanent migrants from San Nicolas work abroad in various countries, usually the United States. Meanwhile, there are approximately 3,300 temporary migrant workers from Moncada abroad, mainly female domestic workers.

San Nicolas is balancing agriculture with urbanisation. The landlocked municipality has extensive farmland which is irrigated with rainfall collected in small reservoirs. The 500 kilometre MacArthur Highway, which begins in San Nicolas, houses a shopping mall, which stands tall within the town’s built environment, as well as several car dealing companies and hotels. There are also 27 financial institutions, including branches of commercial banks with Automatic Teller Machines (ATMs) within San Nicolas.

Moncada is a predominantly agricultural town producing high-value crops such as sweet potato and onions, as well as rice and corn. The town centre houses the entrepreneurial alley of Moncada, the public market, located on the MacArthur Highway. The public market is where most of Moncada’s enterprises operate since villages are spread widely. Many enterprises are small scale; it was only recently that a well-known Filipino fast food chain (Jollibee) opened a branch in Moncada.

Moncada has a few banks, only one ATM, and microfinance institutions operating locally, as well as two of the province’s largest cooperatives (or credit unions). But Moncada faces two notable constraints: it does not have much additional commercial space available, especially in the public market; and its southern part is shaped like a basin that makes the town prone to flooding. This topographical fact, as local informants had pointed out, becomes a disincentive for would-be investors (including those from Moncada working overseas who might otherwise want to open businesses there).

A family in Moncada, Tarlac makes it known to her townmates that the support of loved ones in Canada has made this bungalow back home possible. (Photo by Jeremaiah Opiniano | Moncada, Tarlac, Philippines | May 2019.)

The geography of rural communities (e.g. location, topography), their economic activities and presence of financial institutions all influence the use of remittances by migrant families. In the case of these two municipalities, it appears that greater levels of urbanisation result in migrant families using more of their foreign earnings within the community.

Local governance also plays a role

Both municipalities are multiple-year winners of the Philippine government’s Seal of Good Local Governance award. The award implies that the two local governments have instituted and operationalised reforms in public services, including local investment services such as business, building and occupational permits. Both local governments have also implemented infrastructure development and improved social services over recent years.

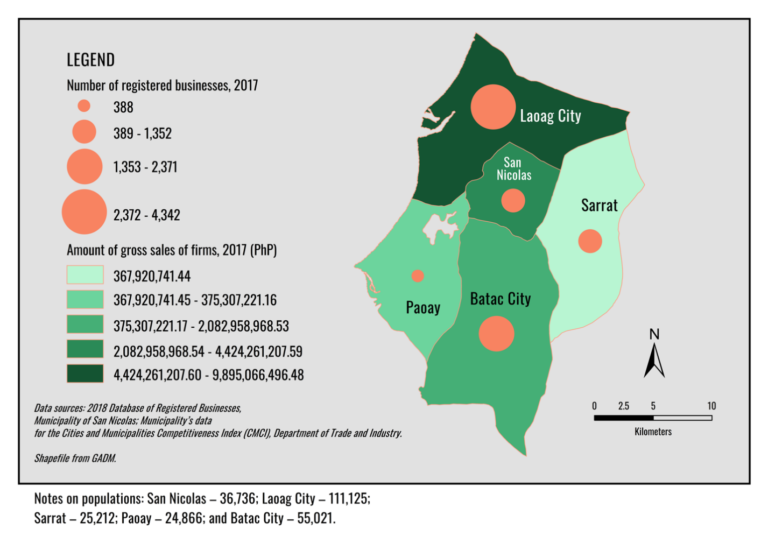

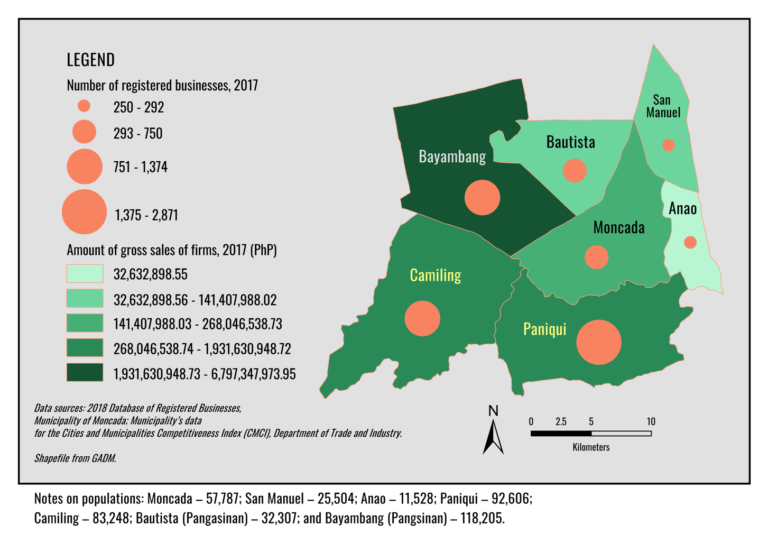

What have been the outcomes of those local governance reforms economically? Data show that San Nicolas had more registered business than Moncada, with the former also getting increased local revenues (tax and non-tax) over the past 17 years to 2019, including local business taxes. San Nicolas has been taking advantage of its strategic geographic location and the commercial and industrial spaces available for investors. Moncada, for its part, is capitalising on its agricultural productivity to lure farmers, ‘agri-entrepreneurs’ and buyers of farm produce from neighbouring municipalities that are richer than Moncada (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). Moncada also benefits from provincial government-run financial inclusion programs for farmers, cooperatives and local entrepreneurs.

If local communities feel efficient services for entrepreneurs and investors are available from their local governments investors will follow, including community members working abroad. Business and investment funded by remittances provide contributions to these rural communities’ economic activities.

Figure 1. Access to external markets – San Nicolas

Credit: Opiniano and Bernardino dela Cruz.

Figure 2. Access to external markets – Moncada

Credit: Opiniano and Bernardino dela Cruz

The impact of access to financial services and levels of financial literacy

Over half of survey respondents from San Nicolas and Moncada claimed to have ‘satisfactory’ or ‘good’ levels of knowledge and skills relating to money. Most respondents first learned about money through their own experiences. At least four in 10 migrant households said they did not need any help handling money.

However, other responses imply that remittance households’ financial behaviours may contradict what they claim to know about financial management. For example, nearly 60 percent of respondents from both towns do not keep financial records, saying they ‘know in general’ how much money is earned and spent monthly.

In addition, respondents from San Nicolas more likely agreed that they never had unspent incomes (M=3.48). Respondents from Moncada, for their part, were more likely neutral in saying they have unspent amounts (M=4.48), yet tended to agree to always having unspent remittances (M=5.36). [This eight-point Likert scale had 1 as ‘never’ and 8 as ‘always’.]

Financial institutions have invited migrant households to use savings products that offer competitive interest rates, but not many have used them. Some households have borrowed money from these institutions, with some reporting that they diligently paid back the loans and others admitting they avoided loan repayments. As for households who did not save, invest or use their remittances for business, they declared that either their incomes were ‘insufficient’ to open savings accounts or make investments in property, or that they do not have the entrepreneurial acumen.

Have overseas migrants from San Nicholas and Moncada found it worthwhile to invest, save and do business locally?

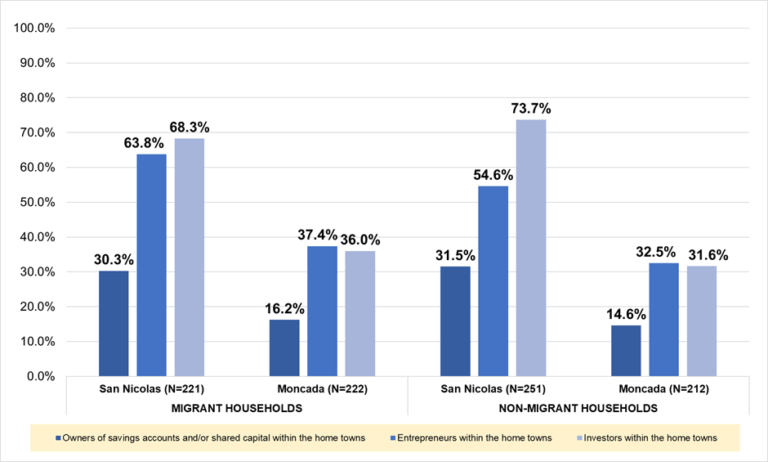

My research found that overseas migrant households from San Nicolas invested, ran enterprises and owned savings accounts in their home town more than migrant households from Moncada (see Figure 3). Even if surveyed non-migrant households serve as a comparison group in the study, similar trends were seen: there were more investors and savers from San Nicolas than counterparts from Moncada.

Figure 3. Migrant home town savers, entrepreneurs and investors in San Nicolas and Moncada, Philippines (Opiniano, 2021)

The top investments and entrepreneurial ventures of surveyed households differed in the two towns. Migrant and non-migrant households from San Nicolas mostly became involved in services-oriented businesses (especially running small retail stores) given the influx of people using the shopping mall. Those in Moncada mostly ventured into farming and some small retail stores (especially in the inner villages) with less than five employees.

Is there any ‘uniform’ formula for the success of remittances?

The lessons from San Nicolas and Moncada show that there may be no uniform formula to assess whether remittances contribute to improving rural livelihoods; rather, it is context specific. Localities’ economic and topographical make-up differ. Access to financial services also differ. Further, not surprisingly, families of migrants differ in terms of relationships, migration profiles (e.g., years of stay abroad, occupation) and family finance dynamics.

These conditions influence remittance owners’ decisions as well as their behaviours in relation to their communities, local government and financial institutions. The potential of remittances to improve rural livelihoods hinges on people’s conduct (agency) and the socio-economic, political, and cultural contexts of a place (structure) where decisions and actions operate.

In addition, there are elements that must be present for remittances to be used to their full potential in the origin communities of overseas migrants: good local governance, facilitative business climate-related services, responsive financial institutions, and more financially literate rural residents.

Main image: Responsive local governance by the Philippine municipality of San Nicolas has supported the agricultural sector, to include those farming families receiving overseas remittances. (Photo by Jeremaiah Opiniano, December 2018, San Nicolas, Ilocos Norte, Philippines)