Malaysian art is gaining international recognition for its focus on climate change and other environmental issues and as a tool for social change, particularly in relation to Indigenous communities. Highlighting the environment is not entirely new. Art historian Sarena Abdullah has documented the rise of critical environmental consciousness among artists since the 1990s up until 2010.

I focus here on artwork produced from 2010 onwards in particular, the works of contemporary artists from East Malaysia (also known as Malaysian Borneo) and artists whose work involves Indigenous and environmental issues. The more political artists are concerned by the combination of corruption, capitalism and greed that enables environmental degradation and the loss of Indigenous customary land as well as the global nature of the problems and solutions.

Political and geographical context

Indigenous peoples are the majority in East Malaysia (50 percent in Sarawak and 62 percent in Sabah), whereas in Peninsula Malaysia, where Malay Muslim culture dominates, Indigenous people constitute just 0.8 percent of the population. Collectively Indigenous Malaysians are known as Orang Asal. Despite being the majority and having some political power in East Malaysia, there are ongoing issues with corrupt political leaders, exploitation of natural resources, subsequent environmental issues and the uneven distribution of wealth and standards of living. The art highlighted in this article connects to these populations and the critical issues that they face.

The art of Red Hongyi

Among the millennial artists of Borneo discussed here, perhaps the most well-known is Kota Kinabalu-born ethnic Chinese Malaysian artist Red Hongyi (b. 1986). Her artwork was featured on TIME magazine’s special issue on climate change on April 26 2021. The headline ‘Climate is Everything’ introduces a map of the world made up of 50,000 green-tipped matchsticks which are then lit. A short video captures the map in flames.

Hongyi and her team spent eight hours a day for two weeks creating the map with individual matchsticks, which only took two minutes to burn down. The artist drew an analogy between this and how the earth was formed over millions of years but could be destroyed by humans in a relatively short span of time. Made during the COVID-19 pandemic, the artwork also implies how global warming or forest fires, like the pandemic, are not limited by national borders—stressing the urgency to address this issue through global cooperation. While the artist’s statement about the work did not specifically mention logging, between 1973 and 2010, Red’s home state of Sabah lost 40 percent of its forests and Sarawak lost 23 percent, according to a 2014 study. A 2013 study found that 80 percent of East Malaysia’s forests had been heavily impacted by logging.

The late period paintings of Inauk S. Gullah

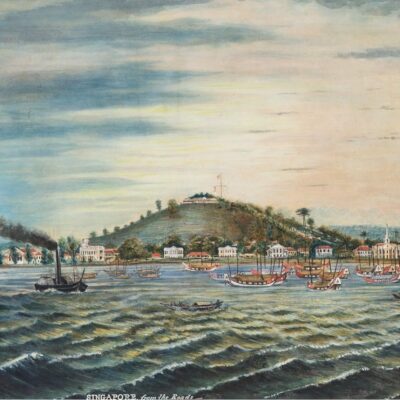

The effects of rapid deforestation and logging on biodiverse landscapes are expressed by under-studied artist Inauk S. Gullah whose painting titled ‘36 Jenis Buah dalam Hutan Pupus Akibat Pembalakan Haram di Sabah’ (2011) (36 Fruits in the Forest Extinct because of Illegal Logging in Sabah) was part of ‘The Plantation Plot’ exhibition (20 April–21 September 2025), at Ilham Gallery Kuala Lumpur.

Image 1: 36 Jenis Buah dalam Hutan Pupus Akibat Pembalakan Haram di Sabah’ (2011) (36 Fruits in the Forest Extinct because of Illegal Logging in Sabah). Published with the permission of the Sabah Art Gallery.

Gullah (b.1938 – d.2020), a Murut Paluan pastor and self-taught artist from the interior of Sabah, highlights the indigenous fruits of the forest through the contrast of colours: a bright green leafy background with fruit in black, red, yellow and brown individually labelled by their Murut Paluan names in white text. On the top right-hand corner is a truck carrying logs.

Another piece ‘Dunia Sabah Yang Hilang’ (The Lost World of Sabah, n.d.) housed in the Sabah Art Gallery, also expresses concern about the loss of Borneo’s unique biodiversity and functions as visual and linguistic memories of the past. ‘Dunia Sabah Yang Hilang’ shows different species of flowers and animals such as the Rafflesia, pitcher plants, wild orchids, buffalo, elephant and a clouded leopard.

Rarely exhibited outside Sabah, Gullah’s paintings have what art writer Max Crosbie-Jones characterises as a ‘faux naïve quality which teem with untrammeled life and rhizomatic abundance’. But Gullah’s work is different from more commercial Sabahan artists of his generation due to his moral vision and criticism of the Sabahan state and society, given to destruction of the natural environment through war, pollution and deforestation, which are both local and global issues.

The art of the Pangrok Sulap collective

Gullah’s sensibility and ethical vision are echoed by a younger generation of Indigenous ‘artivists’ bringing attention to many issues faced by their communities.

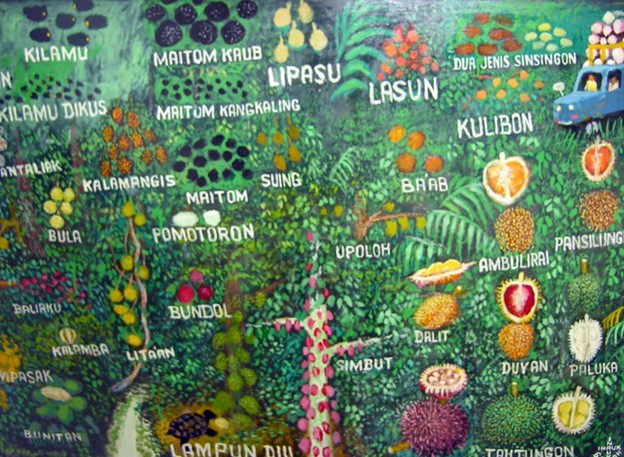

Pangrok Sulap (est. 2010), a Sabah-based collective of artists, musicians and social activists, covers similar issues in their woodcut prints, to the extent of facing censorship. ‘Pangrok’ which derives from ‘punk rock’ and ‘sulap’ meaning ‘resting hut’ in the Dusun language reflects its punk ideology (anti-oppression, solidarity with the marginalised) and DIY (Do It Yourself) sensibility. Their artwork, featured in their 2023 book, focuses on rural empowerment, socio-political critique, and environmental protection. The group holds woodcut workshops for the public and uses art to raise funds to purchase water filters for remote villages and support the LightUpBorneo project to provide electricity to Indigenous communities.

Image 2: Tinagas Keiyep (2018). Woodcut by Pangrok Sulap with Kampung Keiyep. Published with permission from Pangrok Sulap and Tinagas Keiyep.

Some of the Collective’s artwork are community engagement projects featuring stories from villagers from Kampung Keiyep and made with their help. Photographs in the Collective’s book and videos on their Instagram account capture how integral teamwork is to the process of producing their woodcut prints. Resembling performance art, the final step of printing includes community members performing the traditional Sumazau dance on top of the carved blocks and cloth.

As the Collective grows and evolves it is broadening alliances with like-minded artists collectives all over the world. They collaborated with Taring Padi in Yogjakarta, Indonesia, and Patani Art Space, southern Thailand on an woodblock print exhibition entitled ‘Tolong Menolong’ (To Help One Another). Pangrok Sulap’s co-founder, Rizo Leong (b. 1984), appeared in ‘A Visual Diary: The Process of Making Art’ which was presented at the Telur Pecah 4.0 Contemporary Art Exhibition at GMBBKL (Oct 10 – Nov 10, 2024). His pieces called ‘Resilient Future’ and ‘Seeds of Hope’ (made from soaking fabric in alum and then using the green dye from leaves harvested from his garden) demonstrate reduced reliance on commercial ink and suggests a kind of DIY creativity born out of anti-capitalist aims or paucity, one that is simple yet time-consuming and not as convenient as buying mass-produced goods.

Much of this art is ‘socially responsive,’ to quote scholars Clara Ling and Sarena Abdullah, due to its potential to inform and work towards social change.

The art of Shaq Koyok

Another Indigenous community-driven artist who is gaining international attention is Shaq Koyok (b. 1985). He grew up in the Orang Asli village of Pulau Kempas, located in a peat forest close to the Kuala Langat North Forest Reserve, Selangor. Witnessing the deforestation near his village due to a development project left a lasting impression. While the Temuan villagers’ one-week standoff against the developer did not manage to halt the project, it motivated Shaq to use art to speak out about environmental issues and Indigenous rights.

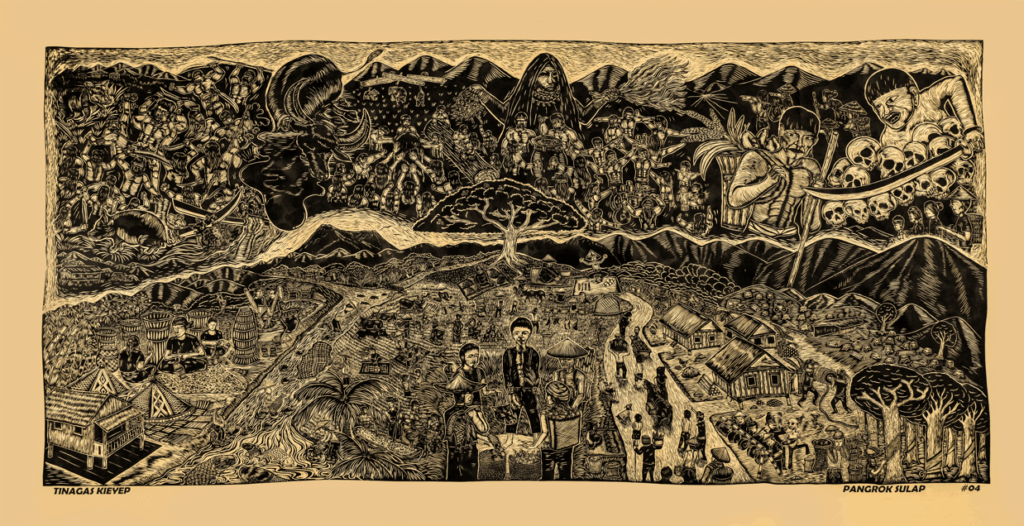

Image 3: Shaq Koyok: ‘Legacy’, Acrylic on canvas, 92 x 92cm, 2020. Published with permission from the artist.

His works engage with key local issues: the struggles of land rights and displacement by dams (Stop Telom Dam 2015), logging (Age of Tomorrow 2016), deforestation and its impact on humans and tigers, and (perhaps, venturing into Indigenous animist beliefs) humans-in-tiger-form or tigers-in-human-form. Legacy features a Jahai boy wearing a tiger suit staring up at the viewer while standing on grey ashy land with blackened tree stumps and oil palm saplings as far as the eye can see under a grey sky. Another work, The Nightmare of Moyang Bajos (2021), portrays a lone Mah Meri dancer performing the Puja Pantai ritual amidst tree stumps in what used to be a mangrove forest with dark clouds looming overhead and an oil rig platform and ships in the distance. His early portraits of Indigenous characters were painted on woven mengkuang mats made by his mother and other relatives, highlighting Indigenous women’s traditional art using sustainable materials.

His portraits, whether on buildings, canvas or woven pandanus, acknowledge Orang Asli as custodians of the land who persist through their resilience and survival: A Temiar elder who has been resisting the durian plantations and logging in Gua Musang and the Jahai boy who is part of the Mendraq Patrol (Indigenous forest rangers preventing poaching and trapping of tigers in the Royal Belum Forest) among others, are part of his solo exhibition ‘Land of a Thousand Guilts’ (2021). In a New Straits Times interview in 2024, Shaq stated, ‘Our identity is rooted in the land we inhabit. Being displaced is comparable to being torn from your soul and spirit, […] Yet we’re still being pushed away from our homes and deprived of our identity.’

The art of Syarifah Nadhirah

Syarifah Nadhirah’s (b. 1993) book Recalling Forgotten Tastes focuses on cataloguing Malaysia’s edible plants based on Indigenous knowledge. A non-Indigenous artist, Nadhirah, together with Rizo Leong of Pangrok Sulap, was chosen to participate in ‘Time of the Rivers,’ an artist fellowship programme which is part of Human-Nature, sponsored by the British Council. Her solo exhibition ‘Measure of Seeds’ explored the memory of plantation histories in Malay/sia, the idea of plant migration and the relationship between pollinators, pests and the specific plantation crop (be it coffee, tapioca, gambir, pepper or rubber). Her agro-ecological work is critical of colonialism and capitalism and recognises the devastation of the soil caused by monocrop agriculture.

The sculpture of M. Sahzy

Lastly, we turn to the organic works of artist-sculptor is M. Sahzy (b. 1995), an Iban-Malay who resides in Kuching, Sarawak, which has a thriving art scene. Sahzy, a self-proclaimed environmental artist relates to the potential of natural materials in his surroundings to tell a story. In an 2023 interview, he explained: ‘I investigate the possibilities that exist within the materials; in addition, each sculpture represents a special experience that the materials would have offered over weeks or months [that it took to make them]. The materials become the text, and the sculpture becomes the story.’ In the process, there is a recognition of objects possessing some agency, having what philosopher Jane Bennett calls ‘thing power’ and acting as ‘vibrant matter.’ Sahzy’s relationship to the natural materials he works with (wood, vines and found objects) is cultivated through time, giving a sense of equality to the materials as one would to develop human relationships. Moreover, his wooden sculpture of a human face emerging from a driftwood captures the connection between humans and nature.

Following an Iban belief that humans can be led astray by orang bunian (forest spirits) while in the jungle, Sahzy converts found natural objects into artistic ‘mystical portals’ to help humans stay within the human realm. Acting sustainably, he returns the materials from these installations to the forest after exhibition. As an environmental artivist and filmmaker, Sahzy’s work also includes short videos which incorporate his sketches of animals (the hornbill, pangolin) and plants (the pitcher plant), drawn in the style of botanical drawings and accompanied by English text, which explains their ecological cultural significance and thus necessity for conservation.

Conclusion

The contemporary Malaysian art discussed here displays a deep concern about critical environmental issues that are disproportionately impacting rural and Indigenous communities. Deforestation and various destructive development projects such as dam-building and mining signify displacement and disempowerment and diminish whole ways of life, culture and knowledge tied to the land. For Orang Asal, nature is culture and the overlap or continuum of the two is recognised in different ways in the contemporary art discussed here, with many artists reclaiming their ethnic identity and culture or connecting with local histories and traditional arts and crafts. Of course, other artists not discussed here, in their own ways and styles, also represent Indigenous pride and experience (such as Iban-Bidayuh Brandon Ritom’s plein air landscape paintings and portraiture and Bidayuh artist Kendy Mitot’s explorations of Bidayuh cosmology and spirituality) and highlight the role of Indigenous women (Temuan artist Leny Maknoh’s realist portraits in pencil and internationally established artist Yee I-Lann’s recent collaboration with sea-based and land-based communities and Indigenous mediums in Sabah where weaving features as an emblem of nature-culture).

Taken together these creative artistic gestures are decolonial attempts to give voice to Orang Asal and to reclaim cultures long regarded as undeveloped, backward and standing in the way of economic and scientific progress. They contribute to globally relevant conversations about an interchange of Western and local Indigenous knowledges to help create sustainable futures.