Environmental degradation in Myanmar has intensified since the coup d’état on February 1, 2021. Throughout the country, unregulated resource extraction is unleashing broadscale devastation exacerbated by civil war and climate change. The situation is especially acute in Kachin, the northernmost state of Myanmar, which forms part of the country’s 2,100-kilometre border with China. Remarkably biodiverse, Kachin State has become an increasingly contested site vulnerable to ecological and social exploitation.

Rare earth mining and environmental catastrophe

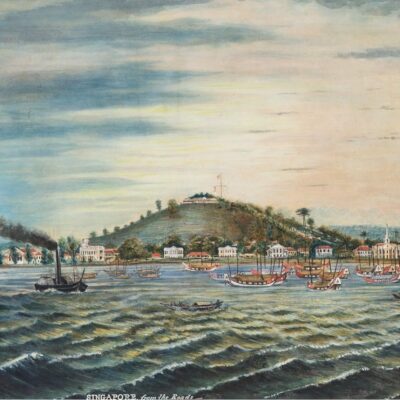

The post-coup escalation of rare earth mining is a major contributor to Myanmar’s present crisis. Valued for their conductive qualities, these metals are essential to electric vehicles, wind turbines and military technologies. Myanmar ranks as the third-largest producer of rare earths, after China and the United States, with a 158 percent upsurge in output between 2022 and 2024. Nearly all of Myanmar’s mines are located in Kachin State in an area the size of Singapore along the Chinese border.

Longstanding armed conflict between the Myanmar armed forces, or Tatmadaw, and Kachin separatists is exacerbating the effects of the rare earth boom, triggering a humanitarian catastrophe. Over the last 15 years, recurring clashes between the military armed forces and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) have precipitated the internal displacement of nearly 100,000 people. Most rare earth operations are located in the chronically impoverished yet mineral-rich Pangwa-Chipwi area seized by the KIA from the military government in late 2024.

Despite the high risk of censorship and incarceration, creative actors continue to respond vigorously to the environmental crisis gripping Kachin State. In 2011, a fusion of activism, art and performance inspired the successful campaign led by photographer and activist Myint Zaw to halt the construction of the Myitsone Dam at the headwaters of the Irrawaddy River. Yet the defiance of authoritarianism typified Burmese art well before the junta took control in the 1960s. In the colonial era (1824–1948), artists used parody, satire, metaphor and other methods to advance political critique and promote societal liberation.

Interwoven histories: Creativity and politics in Myanmar

Creative expression and political activism share a tight historical connection in Myanmar. During the early twentieth century, revolutionary poets inspired the drive for independence. Prominent among them was Maung Lun, later known as Thakin Kodaw Hmaing, whose writing criticised the country’s leadership for short-sighted political gains at the expense of national liberation. After British rule for more than a century, Myanmar became a sovereign republic in 1948 owing, in part, to the politically transformative power of artworks, poems and other nationalistic creativities.

From 1962 until the general election of 2010, a military dictatorship assumed governance of the fledgling nation. For five decades, totalitarian laws harshly constrained the freedom of poets, novelists, musicians, performers, comedians and cartoonists. This period saw the shuttering of the Independent Press Council, the nationalising of newspapers and the imprisoning of dissenters. Many activists who participated in the pro-democracy protests of 1988 and 2007 amplified their messages through poetry, songs and performances.

Political reforms between 2011 and 2015 eased laws censoring the press and Internet. During these years of media liberalisation, Myanmar became the ‘fastest growing Internet market in Asia.’

In the 2015 election, poet and environmental activist U Yee Mon (pen name, Maung Tin Thit) of the National League for Democracy (NLD) defeated a former military general as a candidate for Parliament. Imprisoned by the junta for seven years following the 8888 Uprising, Maung Tin Thit has leveraged his writing over many decades to advocate democratic ideals. His work before and after Myanmar’s brief foray into media liberalisation exemplifies the steadfast commitment of creative actors to political change.

During the same period, the new government resumed than gyat competitions. Traditionally held during Thingyan, the water festival marking the Burmese New Year, thang yat performances often confront social and political injustices through satire. Although broadcast nationally, the competitions were subjected to a pre-censorship process. Nonetheless, the performances brought public attention to ecological urgencies such as water pollution caused by the Letpadaung Copper Mine in the Sagaing Region and Myitsone Dam in Kachin State.

Under the leadership of Htin Kyaw and Aung San Suu Kyi, a new parliament convened in 2016 but the democratic transition would prove short-lived. In response to nation-wide upheaval, ecological creativity in Myanmar continues to intertwine with political activism, as we see in the case of Kachin State.

Kachin State: Biological and cultural diversity in a zone of Contamination

Fractured by secessionist fighting since the 1960s, Kachin State is one of the most politically turbulent places in Myanmar. In the years following independence from Britain, tensions with the central government boiled over as Kachin leaders pushed for greater autonomy. Ceasefires have failed repeatedly during decades of conflict between the military armed forces and KIA. Spurred by resentment towards government assimilation policies, militia groups vie for access to teak, jade, amber, gold, iron and rare earths.

This long-term instability is also imperiling Kachin’s biological heritage. Nearly all of Myanmar lies within the Indo-Burma biogeographic region or ‘biodiversity hotspot’. In this northernmost area, the Indo-Burma hotspot intersects with the Himalaya and Mountains of Southwest China regions, producing exceptionally high faunal, floral and fungal variety. Located on the eastern Himalayan slopes, one of the last intact Southeast Asian forests, the Hkakabo Razi landscape, harbours approximately 40 percent of Myanmar’s bird and bat species, many of which are endemic. In contrast, the extent of Kachin’s botanical diversity remains ‘largely unknown’ and a ‘virtual black spot’ for ecologists.

Closely connected to its natural wealth is Kachin State’s ethnic complexity. The Kachin Confederation is one of Myanmar’s eight major ethnic groups. Comprising the confederation are the Kachin (or Jinghpaw, the largest at about 38 percent of the population), Lhaovo, Lachid, Zaiwa, Lisu and Rawang. Throughout the state, Jinghpaw language is spoken as a lingua franca. Intergenerational ecological knowledge, especially of plants, remains a significant part of local health care practices and spiritual traditions. Yet as international demand for critical minerals skyrockets, the future of much ethnobiological knowledge is becoming precarious.

Rather than open pits, rare earth mining in Kachin State involves in-situ leaching. Chemicals injected into the ground through pipes create a mineral solution collected in ponds. The effects of this toxic process on local people, soil, water, wildlife and vegetation have led researchers to characterise Kachin State as a ‘sacrifice zone’. This concept refers to places exposed to extreme contamination where residents suffer the physical and psychological repercussions of mining, dam-building and logging. These forms of extractivism thrive on the ecologically and socially disastrous amassing of capital. Reflecting the historical interplay between art and politics in Myanmar, contemporary Kachin environmentalism in defence of rivers integrates creative approaches to great effect.

In defence of rivers: The Myitsone megadam

The Irrawaddy (Ayeyarwady or Mali-Nmai-Hka in Jinghpaw) is Myanmar’s most culturally and economically significant river. Emerging at the junction of the N’Mai and Mali rivers, the Irrawaddy flows south for 2,400 kilometres before reaching the Andaman Sea. Kachin communities regard the confluence as a sacred area, ancestral heartland and source of livelihood. In 2009, construction of a massive hydropower project began. The plan included a cascade of seven dams culminating in the Myitsone dam, named after the Burmese word for ‘confluence.’ The potential displacement of 18,000 people and the inevitable desolation of the environment garnered nationwide attention through the ‘Art of the Watershed’ exhibition.

Image 1: People viewing the ‘Art of the Watershed’ exhibition (2011). Image used with permission from the Goldman Environmental Prize.

Anti-dam mobilisation began in 2004 among Kachin activists in response to megadam proposals. The Save the Irrawaddy campaign grew to include musicians, artists, writers, journalists, activists, conservationists and, even, Aung San Su Kyi (who was under house arrest by the military at the time). National focus on the simmering crisis sharpened through the activism of Myint Zaw, a photojournalist known for combining art, poetry and media to advance awareness of the megadam within Myanmar and internationally. Born near the Irrawaddy Delta in southern Myanmar, Zaw has ‘always had a love for the river, which is the lifeblood of our people. Our culture depends on it. This sense of connection led me to become an environmental journalist.’

In 2011, Myint Zaw’s ‘Art of the Watershed’ showed around the country in support of the anti-dam movement. The series of exhibitions aimed to raise awareness of the Irrawaddy’s ecological value through photography, art and writing. The exhibitions, moreover, allowed the campaign to circumvent government restrictions on public meetings. According to Zaw, ‘through our photographs and artwork, we wanted audiences to visualise the dam’s impact on people’s everyday lives.’ Six days after a well-attended art show in Yangon, President Thein Sein announced the suspension of the Myitsone project. For Zaw, community-based environmental creativity is a catalyst of social transformation beyond the brutal nation-state agenda. Through art ‘we pursue social justice, which for us is to pursue human dignity.’ Although construction ceased, calls to revive Myitsone have been ongoing. In 2024, the junta proposed resuming construction to address the national power shortage. In response to recurring threats, activism grounded in creativity continues to flourish. The film Above and Below the Ground features three Kachin women activists committed to defending the sacred confluence. The film also includes BLAST, a band consisting of Kachin pastors who recorded a music video album protesting the megadam. Spread through underground networks, the album inspired public opposition to the project. BLAST’s songs lament the loss of the natural and cultural heritage of northernmost Myanmar where ‘the Kachins are languishing / Kachins are upside down in their homeland.’

Image 2: Still from ‘Above and Below the Ground’ (Hong 2023). Used with permission of Emily Hong.

In defence of the earth: The Hpakant Jade Mine

The intensification of mining in Kachin State has resulted in forest clearance, farmland degradation, river sedimentation, mining waste, abandoned pits and deep excavations traversing the landscape. Environmental impact assessments, often conducted by the same companies carrying out the excavations, tend to fall short of international standards. Most of the 370 rare earth mines and 2,700 pits in Kachin State lie clustered near the Chinese border. In addition to rare earths, mines extract iron, gold, tungsten, lead, zinc, jade and other commodities.

The world’s largest jade mining complex, Hpakant, produces jadeite, the most valuable form. Despite generating enormous revenues, Hpakant is poorly maintained and prone to broadscale disasters. In 2020, after heavy rain, 172 miners died in a landslide and, five years later, at least 32 people lost their lives in a mine collapse. In both cases, many victims were domestic migrant labourers.

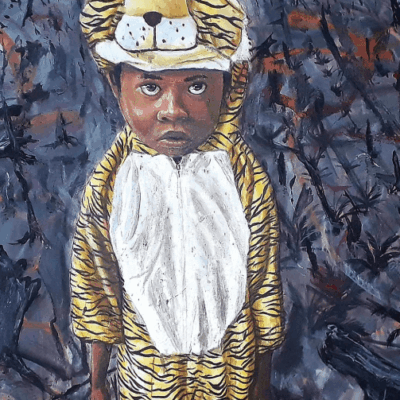

A prominent Kachin artist whose work attends to the crisis of extractivism is Ko Z, or Zahkung Hkawng Gyung. Through paintings, cartoons and performances, often satirical in nature, Ko Z confronts his homeland’s despoliation. ‘My respect and love for Mother Nature is a heritage from my ancestors. It hails from my Kachin ethnic origin and from my childhood.’

Mining’s devastating effects recur thematically across decades of his work. The 2005 cartoon ‘Save the Environment’ centres on a barren, desiccated landscape. An axe is tucked into the traditional dress, or longyi, of a male figure with his back to the viewer. The figure gazes at a massive disembodied head of a man with lifeless tree stumps affixed to his scalp, tears streaming from his eyes and his tongue dangling as a rat gnaws on his ear. The illustration embodies Ko Z’s desire to ‘continue creating artworks to raise awareness about environmental issues.’

Ko Z initiated the concept of ‘enviroformance art’ to illuminate the connection between human rights and environmental conservation through artworks performed in natural settings. In 2009, shortly after Cyclone Nargis struck southern Myanmar, he formed the V30 Environmental Art Movement to inspire artists to engage with ecological issues. His performance ‘Into the Wild’ occurred at Thanlyin, a major port city across the Bago River from Yangon. Wearing the foliage of a wetland shrub as a headdress, Ko Z wades into the marshlands. The artist’s transformation into a human-flora hybrid evokes the Kachin people’s interdependencies with botanical life.

In the wake of the 2021 coup, performance art has offered a potent response to extractivism that, simultaneously, complicates the enforcement of censorship laws. Like Ko Z, the performers Yadanar Win, Ko Latt and Ma Ei, known collectively as 3AM, communicate the catastrophic repercussions of mining in Kachin through their bodies. Their video performance Construction and Deconstruction positions the Hpakant landslide of 2020 as symptomatic of the erosion of the country’s stability. From earthen vessels, the artists draw coloured liquid representing the yellow, green and red of Myanmar’s flag. Mixing the liquid with flour, they knead the dough with their bodies on the gallery floor until the colours meld. Eschewing an overt political stance, the work embeds its underlying message in the physical interplay between the performers and the materials. In this way, Construction and Deconstruction issues an evocative critique of the nation-state’s erasure of cultural and biological diversity through rampant mining.

Image 3: 3AM / Myanmar, est. 2016 / Construction and Deconstruction (still) 2021. Used with permission from the artists.

In defence of forests: Banana monocultures

Between 2005 and 2015, Kachin State experienced the highest rate of deforestation in Myanmar. Forests producing teak and other economically prized trees are under particularly heavy pressure.

In 2015, Ko Z curated the ‘Kachin Liberation Art Exhibition’ featuring documentary photography by Hkun Lat on mining’s consequences. Much of Lat’s freelance photojournalism foregrounds the interconnected humanitarian and ecological crises in Kachin. His panoramic photo ‘Temple and Half-Mountain’ juxtaposes the devastated Hpakant minescape with Kachin’s vulnerable cultural and natural legacies. A Buddhist temple is perched on a forest-covered mountain split in half by the encroaching mine. The shrine and its surviving trees cling to an island within the apocalyptic landscape.

Lat’s images also confront the loss of forests to agricultural expansion. His exhibition ‘The Price of Bananas’ called attention to the deleterious impacts of banana plantations on the environment and workers’ health in Kachin. Initially set up in Laos, these plantations were relocated to Kachin after the Laos government shut them down in response to pesticide overuse. The plantations generate enormous quantities of plastic refuse, some of which is burnt onsite. The bananas’ high demand for water has caused rivers, streams and groundwater to dry up.

‘The Price of Bananas’ portrays unprotected workers soaking bananas in vats of chemicals on a tissue-culture plantation. Another image features an elderly woman who lost two fingers after cutting herself with a knife drenched in the same chemicals contaminating the streams. In another photo, the aerial perspective reveals how banana plantations are carved out of Kachin’s dense forests.

The nexus of environment, creativity and politics in Kachin State

In a poem by Kachin writer Wawn Awng ‘Pupa,’ an immature insect symbolises the potential for democratic transformation in Myanmar as it rides ‘the wind’s current / inhales and flies away.’ While signifying the Burmese people’s longing for freedom after interminable conflict, the poem also evokes Kachin’s threatened biodiversity through the image of the pupa.

Like Awng’s poem, artist Brang Li’s ‘Kachin House Boat’ foregrounds Kachin sovereignty. A wooden boat decorated with Kachin motifs rests on a pedestal in the gallery. Piles of salt placed around the boat express the traditional Kachin belief that salt protects people and allows souls to reach the afterlife. The work of Li and Awng gives voice to Kachin ancestors’ deep knowledge of their land and sustainable reliance on its natural resources.

In this spirit, creative actors such as Hkun Lat, Ko Z, 3AM, BLAST and Myint Zaw transcend the repressive nation-state ideology by confronting the entanglement of politics, society and environment in northernmost Myanmar. Despite harsh current constraints on free expression, including severe Internet restrictions and laws against public gatherings, creative activists continue to inspire environmental resistance through a variety of innovative means. Their interventions emphasise the vital role of art, writing and performance as agents of environmental justice in Myanmar in the post-2021 era of accelerating ecological loss.