The construction of dams is a very controversial issue in the Philippines. The Philippine government prioritises dam construction projects due to a growing population and the scarcity of water and energy resources. Dams are cast as a long-term solution for urban communities and industry.

Dams are funded through private and public partnerships that are widely criticised as examples of the profit-driven takeover of public services, as well as concrete measures by which local elites accommodate foreign economic interests.

Dams cause deleterious consequences for human and non-human ecologies in areas where these infrastructure projects are built. They result in the destruction of forests and rivers and the natural habitat of flora and fauna. They also bring about the violent destruction of ancestral territories and the forcible displacement of Indigenous communities.

The Kaliwa Dam controversy

One such controversial project is the ongoing construction of the Kaliwa Dam in the Southern Luzon region. The dam is intended primarily to serve as an additional source of water for the Metro Manila Region, which has experienced serious water shortages in recent years.

The project was first proposed under the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos and has been reignited at various stages by successive post-authoritarian administrations. Under the administration of former President Rodrigo Duterte, the Kaliwa Dam construction made significant progress due to China’s development financing, which the Duterte administration welcomed in what was widely interpreted as a way to secure his political standing. The dam is scheduled to be finished by the end of 2026.

The scope of the project includes the provinces of Rizal and Quezon and is expected to encroach on the ancestral domain of the Indigenous Dumagat-Remontados who live by the mountain ranges of Sierra Madre. The project threatens to submerge Indigenous people’s lands and displace them from their homes. Members of Indigenous communities report being coerced and misinformed about the project and not being properly consulted. This is despite national laws aimed at protecting their rights ‘to their ancestral domains to ensure their economic, social and cultural well being’. There have also been reports of continuing progress without the necessary clearance and permits from government offices.

The dam project has been met with widespread opposition from various coalitions and civil society organisations. An example is the broad multisectoral network called Stop Kaliwa Dam, which has been formed as a unifying alliance on the issue. They have made significant achievements such as the release of local ordinances that oppose the dam construction.

Danger for activists

The Philippines has been named as the deadliest place in Asia for environmental defenders. The government employs red-tagging (the practice of accusing individuals and organisations of being involved with the communist armed movement) against Indigenous peoples, and human rights and environmental activists involved in resistance to the dam project. The result can be the persecution and killing of those who have been red-tagged by state actors and other powerful entities.

Despite this, resistance to the dam project continues. A focal point of activist mobilisation around the Kaliwa Dam project is concerned with the amplification of Indigenous voices that have been silenced and coerced into submission. Here, creative expressions play a crucial role in increasing public awareness of the threats posed by the dam to Indigenous communities, and broadening support for resistance to the project.

The role of documentary films in resisting the Kaliwa Dam

Short documentary films are important tools to raise awareness of the environmental destruction caused by the dam and its effects on Indigenous communities. They are produced by non-government organisations and individuals and circulated on social media platforms and websites such as YouTube for free. These films, largely independent initiatives, are created through digital technologies on shoestring budgets.

Some filmmakers are not from Indigenous groups, but they unambiguously position themselves in solidarity with Indigenous people’s struggle against the dam project’s encroachment on ancestral lands. The films they create centre the voices of Indigenous elders who invoke the close linkages between cultural memory, their sense of community, and their natural environment.

Lunod [Drown], 2024: Tales of the river

Independent filmmaker and former journalist Mads Miraflor’s nine-minute documentary Lunod [Drown] (2024) centers on an Indigenous Dumagat woman who tells the story of the Tinipak river in the Rizal, one of the provinces covered by the Kaliwa dam construction. The documentary, produced by the independent outfit Brilliant Jerk production, opens with the 63-year old Nanay Nelly hearing news that approximately a quarter of the construction is complete.

Nanay Nelly braids her childhood memories with the mysteries surrounding the Tinipak River. Her voice hovers over shots of the beautiful river winding its way across the forested land, as she recalls the tales spun around the body of water, regarded by their community as sacred. She recalls the St. Elmo’s fire, the ghostly apparitions that they call ‘Bibit,’ and the ancestral spirits known as the ‘Nuno’ to whom the community would offer food and betel nut for chewing. The river, in her story, both provides and takes away—giving nourishment to the community but also claiming lives at times. Nanay Nelly, and by extension, her community, believes that it is the wrath of the spirits guarding the environment that causes lives to be taken by the river.

For Nanay Nelly’s community, the Kaliwa dam project is threatening the river’s existence and the surrounding natural environment, further inviting the spirits’ fury. They believe that the dam project is a disrespectful and destructive act that will cause the river to embark on revenge and to take more lives. As the project continues, the river and the surrounding rock formations in the area, captured vividly by the camera drones, will be drowned (malulunod) by the giant dam.

Nanay Nelly’s story potently entwines memory of the past, present and future of the community and environment and illustrates the complex relationship between the natural environment and humanity, which development projects like the dam threaten to disrupt.

Ground Zero, 2020: Lifeways under threat

Ground Zero (2020) is a 13 -minute documentary produced by the International Indigenous Peoples Movement for Self Determination and Liberation and the publication Bulatlat. The documentary features interviews with members of the Dumagat Indigenous community. In a sequence of testimonies that depict the everyday practices of survival of the community, Indigenous leaders detail the modes of livelihood that they source from the river, their traditional ways of healing, and the methods they have developed to draw and distribute water and food across the community.

Revealed in the film is the community’s close relationship with land. Indigenous leaders express how they view the sacred burial ground of their ancestors, which the dam project threatens to obliterate. Conveyed here are collective fears about how external profit-driven initiatives desecrate the memory and heritage of an entire people.

From the sweeping accounts of the various aspects of Indigenous lifeways that are shown in the documentary, the testimonies evoke the sense of dread that grips the community. Inscribed in the faces of the people are expressions of anxiety over the threats from armed state forces. As a result of their opposition to the project, these people experience harassment, with some being accused of being members of the communist movement. But here, even as external forces disrupt the peace in the community, the film captures the resoluteness of the Indigenous community in their stance against the dam.

Kaliwa [Left] 2024: Resistance and solidarity

Kaliwa [Left] is a 20-minute documentary by independent filmmaker and teacher Jade Ora-a. In this film, the Indigenous people residing in the Quezon province, Ora-a’s hometown, share their stories of resistance to the dam project. As in Ground Zero, village elders share the importance of the natural environment to their survival and as their source of cultural nourishment. They also speak of the various forms of harassment and intimidation that they have experienced aimed at eliminating opposition to the project. The interviewees, for instance, tell of the visits from soldiers who attempted to convince them to support the dam project.

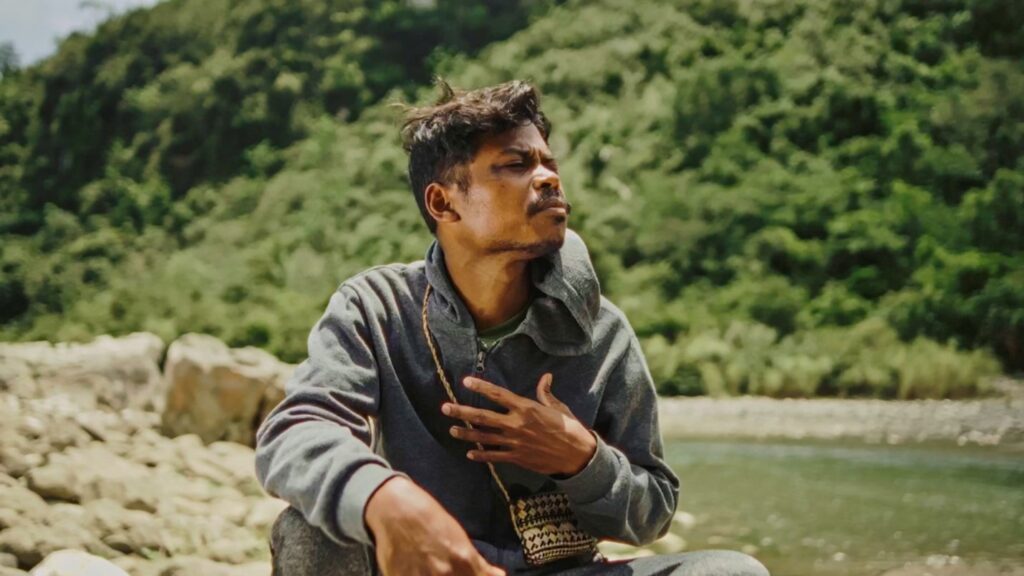

Kaliwa also explores the involvement of Filipino activists who do not belong to Indigenous communities but are working in solidarity with them. A teacher-activist who decides to immerse herself in the community shares the insights she gains from her involvement in the Indigenous people’s fight. Here, a community of political struggle is evoked with cooperation between Indigenous groups and non-Indigenous Filipinos. This sense of solidarity is also conveyed through the inclusion of footage of protest action in urban areas, showing that Indigenous communities are not alone in their resistance to the threats to their lands.

Image 1. A community leader speaks about the dangers of the proposed dam. Still from Kaliwa, used with permission by Jade Ora-a.

Warnings of bleak futures

These films convey a bleak future for Indigenous communities as the dam construction continues. The Dumagat-Remontados people are clear that the dam may spell the death of their community and the surrounding natural environment. As one of the community members states, they may relocate to other areas and start new lives, but they could never recover their rich Indigenous heritage and the natural environment so integral to their culture.

The Kaliwa dam project continues, threatening to submerge over 9,000 hectares of forest and displace over 1,000 families in the provinces of Rizal and Quezon. The construction has however faced delays, as the project also has to deal with technical difficulties and the uncertainties surrounding the Philippine government’s financing deal with China.

Such a situation thus renders complex the future of the Indigenous communities. As conveyed in the documentaries discussed, Indigenous voices remain steadfast in their opposition to the dam. Civil society organisations have also crafted proposals for alternative sources of water for Manila, such as the rehabilitation of forests and existing river basins.

These possibilities can be realised through stronger and persistent organised action. Indigenous communities have held dialogues with concerned government offices, and protest actions. Here, the need to forge solidarity in resistance to the dam, and to continue the struggle is emphasised as a measure of hope to ensure that the Indigenous communities can live in peace.